Alice Brend

Mashantucket Pequot, 1905 - 1995

Names

- Alice Brend

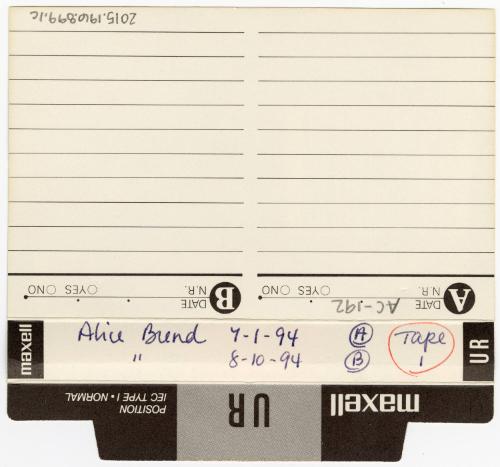

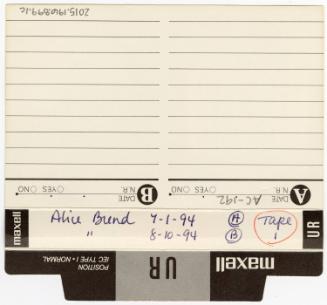

BiographyBorn and raised on the Mashantucket Pequot reservation near Ledyard, Alice Brend (1905-1995) was perhaps the last Connecticut native person to know all phases of the traditional basket making process. Both her mother and grandmother were basket makers, deriving much of the family's income through basket sales to farmers and settlers in surrounding areas. Alice began learning at around age eight, and although she took years off to raise her family, she retained her knowledge and interest in basket making. In 1994, at 89 years old, she no longer pounded logs to produce splints, but began teaching the process to apprentice Mike Guillemette.

Alice's mother was Martha Ann Hoxie, a basket maker who learned her skills from her mother, Jane Elizabeth Wheeler. Martha had fifteen children from two marriages, first to Cyrus George, then to Alice's father Leopold Langevin, who was French. Alice was born in 1905, the second to last of Martha's offspring. Her brothers and sisters weren't interested in basket making, but Alice went along with her mother, watching and learning as she located black ash trees and processed them for basket making. Both her mother and grandmother gave the young girl instruction in all stages of the process, which she still remembered clearly. Over time members of the large family grew up and moved away to raise families of their own. Alice lived off-reservation but nearby with her three children, while her sister Martha and half-sister Elizabeth stayed to become the last two residents on Mashantucket, which had been reduced in the mid-1800s to 214 acres. In the mid-1970s, tribal members began the long process of reclaiming their land and petitioning the federal government for tribal status. Federal recognition finally came in 1983, enabling the Mashantucket Pequots to re-establish their lost land base and achieve economic self-sufficiency.

Alice worked within a centuries-old New England native tradition of forming baskets with splints taken from the black ash tree. Pequot basket makers would first select a good tree with no knots, cut a ten foot length, quarter and soak the log, pound each section on the bark side to separate the tree rings, pull the separated strips apart and plane them to a suitable thinness, then cut the splints into differing widths with wooden gauges. Her mother showed Alice how to do all this herself, before beginning to weave the splints into baskets. The Pequot method of pounding a quartered log to produce splints differs from the Mohawk of New York and the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine, where men pound the entire log. Less labor-intensive, the Pequot way enables a woman to carry out every step of the process.

Basket making requires a number of skills and procedures, as it begins with a tree and ends with a carefully woven vessel. After producing, planing, and gauging the splints, Alice would form the base of a basket by laying out an odd number of stave splints, all cut the same length, then interweaving these with another set of stave splints. Next the fine-width splints are interwoven as the "filling" to work up the sides of the basket. The rim is formed by two thicker splints circling the top, held in place by fine-width splints wrapped around it. Alice would carve basket handles from pieces of wood with her jacknife.

Ill health and difficulties in obtaining suitable splints and gauges in the right widths prevented Alice from working on baskets in her later years. She said that her earlier baskets were mainly made for practice, and that she could have done more work with better access to materials. Her son Gary has become very interested in his mother's basket making knowledge, and is actively searching out materials and resources to carry on the family tradition. One of the most important issues affecting Indian basket making throughout New England is the severe decline of the black ash tree, which is threatened by pollutants and loss of healthy habitat. Along with Alice's memory of the places on Mashantucket where black ash grows, Gary is committed to locating good trees and perhaps organizing a project to establish black ash replanting on the reservation.

Alice's mother was Martha Ann Hoxie, a basket maker who learned her skills from her mother, Jane Elizabeth Wheeler. Martha had fifteen children from two marriages, first to Cyrus George, then to Alice's father Leopold Langevin, who was French. Alice was born in 1905, the second to last of Martha's offspring. Her brothers and sisters weren't interested in basket making, but Alice went along with her mother, watching and learning as she located black ash trees and processed them for basket making. Both her mother and grandmother gave the young girl instruction in all stages of the process, which she still remembered clearly. Over time members of the large family grew up and moved away to raise families of their own. Alice lived off-reservation but nearby with her three children, while her sister Martha and half-sister Elizabeth stayed to become the last two residents on Mashantucket, which had been reduced in the mid-1800s to 214 acres. In the mid-1970s, tribal members began the long process of reclaiming their land and petitioning the federal government for tribal status. Federal recognition finally came in 1983, enabling the Mashantucket Pequots to re-establish their lost land base and achieve economic self-sufficiency.

Alice worked within a centuries-old New England native tradition of forming baskets with splints taken from the black ash tree. Pequot basket makers would first select a good tree with no knots, cut a ten foot length, quarter and soak the log, pound each section on the bark side to separate the tree rings, pull the separated strips apart and plane them to a suitable thinness, then cut the splints into differing widths with wooden gauges. Her mother showed Alice how to do all this herself, before beginning to weave the splints into baskets. The Pequot method of pounding a quartered log to produce splints differs from the Mohawk of New York and the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine, where men pound the entire log. Less labor-intensive, the Pequot way enables a woman to carry out every step of the process.

Basket making requires a number of skills and procedures, as it begins with a tree and ends with a carefully woven vessel. After producing, planing, and gauging the splints, Alice would form the base of a basket by laying out an odd number of stave splints, all cut the same length, then interweaving these with another set of stave splints. Next the fine-width splints are interwoven as the "filling" to work up the sides of the basket. The rim is formed by two thicker splints circling the top, held in place by fine-width splints wrapped around it. Alice would carve basket handles from pieces of wood with her jacknife.

Ill health and difficulties in obtaining suitable splints and gauges in the right widths prevented Alice from working on baskets in her later years. She said that her earlier baskets were mainly made for practice, and that she could have done more work with better access to materials. Her son Gary has become very interested in his mother's basket making knowledge, and is actively searching out materials and resources to carry on the family tradition. One of the most important issues affecting Indian basket making throughout New England is the severe decline of the black ash tree, which is threatened by pollutants and loss of healthy habitat. Along with Alice's memory of the places on Mashantucket where black ash grows, Gary is committed to locating good trees and perhaps organizing a project to establish black ash replanting on the reservation.

Person Type(not entered)

Mohegan, 1899 - 2005