Lydia Howard Huntley Sigourney

American, 1791 - 1865

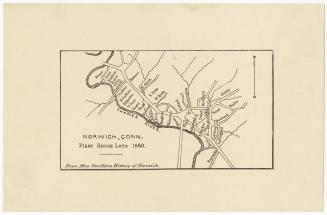

BiographyLydia Howard Huntley Sigourney was born in Norwich, Connecticut on 1791 September 1 to Zerviah Sophia Wentworth and Ezekiel Huntley. Her father was the gardener at the Dr. Daniel Lathrop estate where the Huntley family lived as tenants. Lydia received guidance and support from Daniel’s widow, Jerusha Talcott Lathrop, daughter of Governor Joseph Talcott. Through Jerusha, Lydia was introduced to Lathop's wealthy relatives in Hartford: the Wadsworth family. Following Jerusha’s death when Lydia was 14, she went to live with the Wadsworths in Hartford. There, Lydia attended female seminaries in Hartford where she received an education that included needlework, music, mathematics, Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and philosophy. Her first poem, written at this time, was in honor of Jerusha. In 1811, at age 20, Lydia with friend Nancy Maria Hyde opened a girls’ school in Norwich, Connecticut, where lessons were offered to poor children twice a week. When Nancy became ill, they closed the school. Having befriended Mehitabel Russell Wadsworth, the widow of Colonel Jeremiah Wadsworth, Lydia gained the attention of Mehitabel’s son, Daniel Wadsworth. In 1814, he invited her to head a school in Hartford, at which one of her students was Alice Cogswell. She would be widely respected for her role as an educator. Daniel also encouraged Lydia to publish. In 1815, she published her first book, "Moral Pieces in Prose and Verse", though she did so anonymously. This launched a writing career that would, eventually, make Lydia Huntley Sigourney a household name.

That road was not a straight one. In 1819, Lydia married Charles Sigourney (1788-1854), a wealthy Hartford hardware merchant, widower, and father of three. At the start of her marriage she quit her role as an educator. Charles was initially supportive of her writing – which he viewed as a leisure activity – so long as it was published anonymously. She donated her earned income to charitable causes like peace societies and the temperance movement. Later, he expressed concern about the amount of time she devoted to what was more than a hobby. Disagreement over how Lydia would publish provoked her to ask for a separation in 1827, which Charles refused.

Lydia’s biological children included May and two sons, who died in infancy, along with Mary Huntley Sigourney Russell (1828-1889) and Andrew Maximilian Bethune Sigourney (1830-1850).

After Charles experienced some financial difficulties that led to them move into a smaller home, he softened to the idea of Lydia publishing, especially as her writing began to promote as a virtue women operating within the domestic sphere. As her reputation grew in the early 1830s, Lydia made the decision to publish under her own name, despite her husband’s objections. Besides helping to financially support her own household, she was providing the sole support for her aging parents.

In her lifetime, the prolific writer published 64 volumes of prose and verse, much of which took the form of elegy and conduct literature. Her writing was largely religious in nature and at times promoted Indigenous rights and Abolition. Often, her work was published as “L.H.S.”, “Mrs. Sigourney,” or “Mrs. L.H. Sigourney” as can be seen in the numerous poems reprinted by the Hartford Courant. She died on 1865 June 10 and was buried in Hartford’s Spring Grove Cemetery. Hartford’s Sigourney Street and Huntley Place were both named in her honor.

(Sources: The Norwich Bulletin; New England Historical Society; Poetry Magazine; Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame; Hartford Courant; Lydia Sigourney: Selected Poetry and Prose, edited by Gary Kelly; Provisions: A Reader from 19th-Century American Women, edited by Judith Fetterley)

That road was not a straight one. In 1819, Lydia married Charles Sigourney (1788-1854), a wealthy Hartford hardware merchant, widower, and father of three. At the start of her marriage she quit her role as an educator. Charles was initially supportive of her writing – which he viewed as a leisure activity – so long as it was published anonymously. She donated her earned income to charitable causes like peace societies and the temperance movement. Later, he expressed concern about the amount of time she devoted to what was more than a hobby. Disagreement over how Lydia would publish provoked her to ask for a separation in 1827, which Charles refused.

Lydia’s biological children included May and two sons, who died in infancy, along with Mary Huntley Sigourney Russell (1828-1889) and Andrew Maximilian Bethune Sigourney (1830-1850).

After Charles experienced some financial difficulties that led to them move into a smaller home, he softened to the idea of Lydia publishing, especially as her writing began to promote as a virtue women operating within the domestic sphere. As her reputation grew in the early 1830s, Lydia made the decision to publish under her own name, despite her husband’s objections. Besides helping to financially support her own household, she was providing the sole support for her aging parents.

In her lifetime, the prolific writer published 64 volumes of prose and verse, much of which took the form of elegy and conduct literature. Her writing was largely religious in nature and at times promoted Indigenous rights and Abolition. Often, her work was published as “L.H.S.”, “Mrs. Sigourney,” or “Mrs. L.H. Sigourney” as can be seen in the numerous poems reprinted by the Hartford Courant. She died on 1865 June 10 and was buried in Hartford’s Spring Grove Cemetery. Hartford’s Sigourney Street and Huntley Place were both named in her honor.

(Sources: The Norwich Bulletin; New England Historical Society; Poetry Magazine; Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame; Hartford Courant; Lydia Sigourney: Selected Poetry and Prose, edited by Gary Kelly; Provisions: A Reader from 19th-Century American Women, edited by Judith Fetterley)

Person TypeIndividual

Mohegan, 1899 - 2005

American, 1795 - 1869