Bernabela Quiñones

Puerto Rican, born 1900

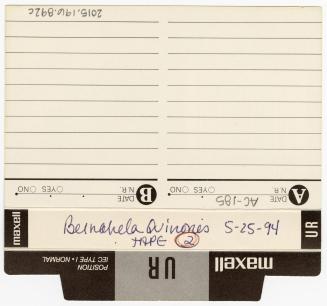

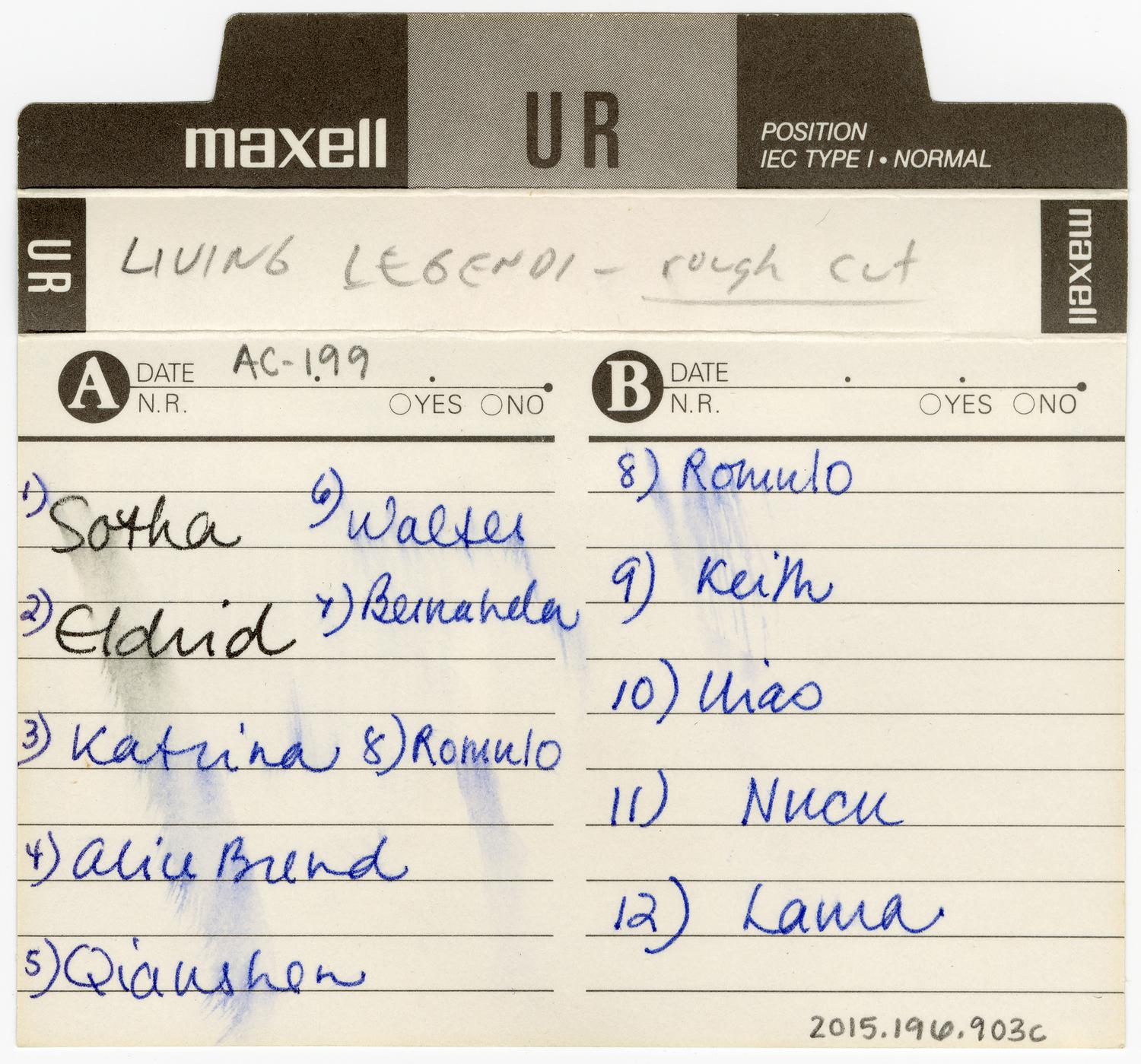

BiographyBernabela Quiñones (Lace Making) was a 94 year old Puerto Rican woman living in Waterbury, Connecticut at the time of the Living Legends Project in 1994. For many years she supported her family by selling her lace work in the Moca area of Puerto Rico, long famous for its textile artists, an endangered art form. Program Director Lynne Williamson and Ruth Glasser, a consultant ethnomusicologist working with the Puerto Rican community in Waterbury, interviewed Senora Quiñones on tape. She described and demonstrated her loom lace making, which she continued as a way to pass the time and to create lace socks for her grandchildren and greatgrandchildren.

The Aguadilla area of northwest Puerto Rico is the home of a lacemaking tradition brought to the island by Spanish nuns. Traditional Puerto Rican lace is made on a small loom called mundillo, because it has a rotating pillow-shaped drum. Doña Bernabela, born February 25, 1900, in the town of Moca near Aguadilla, was still making lace in her Waterbury apartment up until about 1996. When CCHAP visited her in 1994, she stood at her loom, needing glasses only for this activity, continuing to weave lace for occasional sale through an artists' cooperative in Puerto Rico and as gifts to family and friends.

"Eso es lo que nosotros hacíamos antes...ganabamos dinero. Todas las muchachas campesinas...(tenian que caminar) ocho kilometros de camino para buscar trabajo...Esos trajes eran preciosos." (That's what we did to earn money. All the farm girls did it, had to walk 8 miles to look for work. Some of those clothes were beautiful.)

One of seven children in a rural family, Doña Bernabela remembered many stories about her early life. Her father cultivated sugar cane and worked in the mill grinding the cane and tending the fire. The family kept horses, oxen, cows, goats on the farm; they would gather herbs for headaches and other ailments. Because there was so much work to do, she had to leave school in the fourth grade to help. "Mucho sudor, mucho sudor. Uno cogía el machete ...a picar palos en el monte." (A lot of sweat, a lot of sweat. One took a machete...to cut down trees in the hills, for firewood). There were no newspapers, so when a hurricane was coming a man would run barefoot from San Sebastian, Arecibo, or Isabela to warn people, although Bernabela's mother, who was of mixed Indian and white heritage, would also know by the way leaves of a certain tree "turned inside out." Her brother played guitar and cuatro, and they would hold dances in their house.

Lace making was taught to girls in school as early as second grade. When Doña Bernabela left school her older sister, a seamstress, continued to teach her a variety of sewing and embroidery techniques. "Tienes que echar tiempo mirando." (You have to spend time watching.) A common source of income for rural women, lace making and embroidery were also taught through apprenticeships at workshops and factories in the towns. "Yo iba a Agüadilla cada 15 días...a llevar tejido...Una caja." (I went to Aguadilla every two weeks...to get the lace...a boxful." Factories would open at 8:30 a.m., and those not already sewing inside would line up to receive jobs to be taken home. After finishing the orders, the girls would walk back to deliver and pick up another batch. "La paga era muy poca." (They paid very cheaply.) The piecework was sold by the factories to merchants who either exported it to the United States or sold it in San Juan shops.

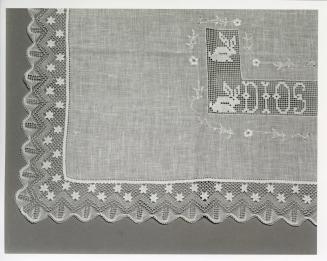

All kinds of fine sewing and textile embellishments were done by island women. Doña Bernabela spoke about making lace baby booties, children's caps, handkerchiefs, pillowcases, petticoats, and yard-long lengths. She was also skilled at embroidery, doing piecework on smoking jackets and children's clothes, specialized needlework techniques such as puntada, calado (openwork), buchipluma, and appliqué, in addition to making gloves and hats. "Antes de soltera cualquier cosa yo hacía." (When I was single I would make anything.)

After her marriage to a foreman in a sugar mill, Doña Bernabela had to put aside lace making to raise her four children and tend the farm. Sometimes she sewed at night to earn money for the family during the "tiempo muerto," the months between sugar harvest and planting, and after her husband became ill and could no longer work. In 1959, she moved to Waterbury to live near her son, supporting herself by washing, cleaning, and cooking for other people. When her husband died in 1975, Doña Bernabela began to make lace again.

Traditional Puerto Rican lace is made on a small loom called mundillo, because it has a rotating pillow-shaped drum. A paper pattern is held in place on the pillow with hundreds of pins marking the design. Thread carried on as many as fifty wooden bobbins (called bolillos) is woven around the pins to make the intricate designs take shape. When we visited her home, Doña Bernabela worked with four bobbins at a time, grabbing one and passing it over the others. At this time she was making baby booties and caps, taking about a week to do a set despite considerable pain in her arm from arthritis.

"Antes aprendían en casa...Hay que poner atencion, poner la cabeza...Antes nosotros en la casa enseñabamos a las muchachitas. Y muchas muchachitas enseñaban a nosotras a tejer...A casa iban unas cuantas muchachas..." (They used to learn in the house...You have to pay attention, put your head to it. We used to show the young girls in our house. And many young girls showed us how to make lace...Many girls came to the house (to learn).)

"Cuando yo estaba en la escuela...cuando entre al segundo grado...en el '11 yo aprendí a hacer estas cosas. En Moca era el pueblo donde abundába eso. En Moca trabajaban todas las muchachas, mucha gente corrían pa'llá y pa'cá tejiendo, bordando, cosiendo. Yo bordaba, yo cosia, yo hacía pañuelos...de todo. Y también cosía a mano. Y entonces yo bordaba con hilo blanco...al realce." (When I was in school...when I entered second grade...in '11 I learned how to do those things. Moca was the town where this work abounded. In Moca all the girls worked, a lot of people running here and there making lace, embroidering, sewing. I embroidered, I sewed, I made handkerchiefs...everything. And I also sewed by hand. And I embroidered with white thread...raised work.)

"Una hacia ese trabajo por el dia y por la noche. Y no habia eso de electricidad, era gas." (One did this work day and night. And there wasn't electricity, it was gas.)

The Aguadilla area of northwest Puerto Rico is the home of a lacemaking tradition brought to the island by Spanish nuns. Traditional Puerto Rican lace is made on a small loom called mundillo, because it has a rotating pillow-shaped drum. Doña Bernabela, born February 25, 1900, in the town of Moca near Aguadilla, was still making lace in her Waterbury apartment up until about 1996. When CCHAP visited her in 1994, she stood at her loom, needing glasses only for this activity, continuing to weave lace for occasional sale through an artists' cooperative in Puerto Rico and as gifts to family and friends.

"Eso es lo que nosotros hacíamos antes...ganabamos dinero. Todas las muchachas campesinas...(tenian que caminar) ocho kilometros de camino para buscar trabajo...Esos trajes eran preciosos." (That's what we did to earn money. All the farm girls did it, had to walk 8 miles to look for work. Some of those clothes were beautiful.)

One of seven children in a rural family, Doña Bernabela remembered many stories about her early life. Her father cultivated sugar cane and worked in the mill grinding the cane and tending the fire. The family kept horses, oxen, cows, goats on the farm; they would gather herbs for headaches and other ailments. Because there was so much work to do, she had to leave school in the fourth grade to help. "Mucho sudor, mucho sudor. Uno cogía el machete ...a picar palos en el monte." (A lot of sweat, a lot of sweat. One took a machete...to cut down trees in the hills, for firewood). There were no newspapers, so when a hurricane was coming a man would run barefoot from San Sebastian, Arecibo, or Isabela to warn people, although Bernabela's mother, who was of mixed Indian and white heritage, would also know by the way leaves of a certain tree "turned inside out." Her brother played guitar and cuatro, and they would hold dances in their house.

Lace making was taught to girls in school as early as second grade. When Doña Bernabela left school her older sister, a seamstress, continued to teach her a variety of sewing and embroidery techniques. "Tienes que echar tiempo mirando." (You have to spend time watching.) A common source of income for rural women, lace making and embroidery were also taught through apprenticeships at workshops and factories in the towns. "Yo iba a Agüadilla cada 15 días...a llevar tejido...Una caja." (I went to Aguadilla every two weeks...to get the lace...a boxful." Factories would open at 8:30 a.m., and those not already sewing inside would line up to receive jobs to be taken home. After finishing the orders, the girls would walk back to deliver and pick up another batch. "La paga era muy poca." (They paid very cheaply.) The piecework was sold by the factories to merchants who either exported it to the United States or sold it in San Juan shops.

All kinds of fine sewing and textile embellishments were done by island women. Doña Bernabela spoke about making lace baby booties, children's caps, handkerchiefs, pillowcases, petticoats, and yard-long lengths. She was also skilled at embroidery, doing piecework on smoking jackets and children's clothes, specialized needlework techniques such as puntada, calado (openwork), buchipluma, and appliqué, in addition to making gloves and hats. "Antes de soltera cualquier cosa yo hacía." (When I was single I would make anything.)

After her marriage to a foreman in a sugar mill, Doña Bernabela had to put aside lace making to raise her four children and tend the farm. Sometimes she sewed at night to earn money for the family during the "tiempo muerto," the months between sugar harvest and planting, and after her husband became ill and could no longer work. In 1959, she moved to Waterbury to live near her son, supporting herself by washing, cleaning, and cooking for other people. When her husband died in 1975, Doña Bernabela began to make lace again.

Traditional Puerto Rican lace is made on a small loom called mundillo, because it has a rotating pillow-shaped drum. A paper pattern is held in place on the pillow with hundreds of pins marking the design. Thread carried on as many as fifty wooden bobbins (called bolillos) is woven around the pins to make the intricate designs take shape. When we visited her home, Doña Bernabela worked with four bobbins at a time, grabbing one and passing it over the others. At this time she was making baby booties and caps, taking about a week to do a set despite considerable pain in her arm from arthritis.

"Antes aprendían en casa...Hay que poner atencion, poner la cabeza...Antes nosotros en la casa enseñabamos a las muchachitas. Y muchas muchachitas enseñaban a nosotras a tejer...A casa iban unas cuantas muchachas..." (They used to learn in the house...You have to pay attention, put your head to it. We used to show the young girls in our house. And many young girls showed us how to make lace...Many girls came to the house (to learn).)

"Cuando yo estaba en la escuela...cuando entre al segundo grado...en el '11 yo aprendí a hacer estas cosas. En Moca era el pueblo donde abundába eso. En Moca trabajaban todas las muchachas, mucha gente corrían pa'llá y pa'cá tejiendo, bordando, cosiendo. Yo bordaba, yo cosia, yo hacía pañuelos...de todo. Y también cosía a mano. Y entonces yo bordaba con hilo blanco...al realce." (When I was in school...when I entered second grade...in '11 I learned how to do those things. Moca was the town where this work abounded. In Moca all the girls worked, a lot of people running here and there making lace, embroidering, sewing. I embroidered, I sewed, I made handkerchiefs...everything. And I also sewed by hand. And I embroidered with white thread...raised work.)

"Una hacia ese trabajo por el dia y por la noche. Y no habia eso de electricidad, era gas." (One did this work day and night. And there wasn't electricity, it was gas.)

Person TypeIndividual