Qianshen Bai

Chinese

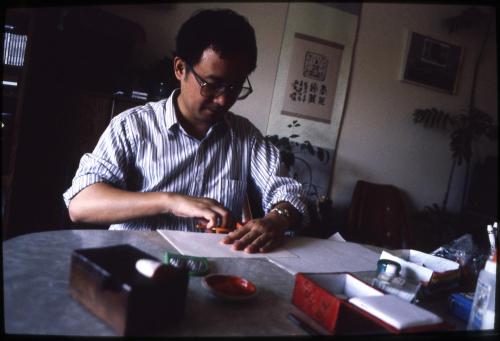

BiographyQianshen Bai began his art as a calligrapher in China, where he first studied with a master teacher while pursuing a career in banking in Shanghai. Qianshen is also an accomplished seal carver, which he describes as "writing in stone." Small stone seals are inscribed with calligraphic characters or ancient symbols. Their imprints have traditionally been used to authenticate documents, signify ownership, or sign a work of art. Seal carving has become an art form in itself, one characterized by both long historical heritage and new contemporary expressions.

Qianshen began to learn calligraphy under the guidance of a master artist in 1972 during China's Cultural Revolution. A revered and popular writing and art form in China for thousands of years, calligraphy also served a valuable function for Qianshen in his work in a Shanghai bank. There, the tradition of calligraphy is taken seriously, because “if you have a check or certificate of deposit, we don't type it - we write it. You have to write beautifully otherwise people will think the certificate is not so serious - it doesn't look like money!" While attending Peking University he organized a student calligraphic society with friends, winning the National Calligraphy Competition for University Students in 1982. His interest in seal carving developed when one of the calligraphy group members, himself a skilled carver, taught Qianshen the art of etching tiny calligraphic characters on stone seals.

Seal carving is a miniaturist's art with a practical purpose. Historically, seals have been used to authenticate documents, signify ownership, or sign works of art and literature among the educated, commercial, and bureaucratic classes. Many Chinese, especially those occupied in business or the arts, still use one or more seals to establish ownership or creativity. New schools and genres of carving have arisen, reflecting the opening up of traditionally elite arts to a wider public in modern China. Qianshen uses an "iron brush" to etch ancient characters into stones selected for their subtle colors, textures, and markings. These small stone seals are inscribed with calligraphic characters or ancient symbols, a process he describes as "writing in stone." Often a person will use more than his or her given name, depending on the situation. For variety a name with a related meaning could be used, or a poetic name of one's home. Some people will also take a literary name, an epithet; and perhaps a studio name if they are artists. Qianshen has made a seal for his given name, one for his special name, and one with a studio name, which is "Cloud Studio - I wish I could be a white cloud floating in the sky so freely."

The production of seals requires a delicate calligraphic skill, as the stones are carved with script characters or similar pictorial figures like Qianshen's "auspicious bird." Another seal carries the common greeting "good luck". "In ancient China the character for sheep means good luck, because the sheep was the animal for sacrifice in worship of ancestors...this sacrifice will bring them good luck." The design is etched into the end of the seal stone with a small chisel, an "iron brush," in mirror image because when impressed it will be normal. Sometimes the character is positive, raised, and sometimes sunken for a white impression. To print, the seal is pressed into a cinnabar (sulphide of mercury) and oil paste.

When he was a doctoral candidate in Chinese art history at Yale University in the mid-1990s, Qianshen practiced both calligraphy and seal carving. In 1992, he co-organized an exhibit at the Yale Art Gallery entitled "The World Within a Square Inch: The Art of Chinese Seal Carving." He also developed an exhibit of Chinese calligraphers working in the last decade of the 20th century. Qianshen became Associate Professor of Art History at Boston University where in 2007 and 2013 he received grants to teach apprentice the elements of calligraphy under the Massachusetts Cultural Council’s Folk Arts Program.

Qianshen began to learn calligraphy under the guidance of a master artist in 1972 during China's Cultural Revolution. A revered and popular writing and art form in China for thousands of years, calligraphy also served a valuable function for Qianshen in his work in a Shanghai bank. There, the tradition of calligraphy is taken seriously, because “if you have a check or certificate of deposit, we don't type it - we write it. You have to write beautifully otherwise people will think the certificate is not so serious - it doesn't look like money!" While attending Peking University he organized a student calligraphic society with friends, winning the National Calligraphy Competition for University Students in 1982. His interest in seal carving developed when one of the calligraphy group members, himself a skilled carver, taught Qianshen the art of etching tiny calligraphic characters on stone seals.

Seal carving is a miniaturist's art with a practical purpose. Historically, seals have been used to authenticate documents, signify ownership, or sign works of art and literature among the educated, commercial, and bureaucratic classes. Many Chinese, especially those occupied in business or the arts, still use one or more seals to establish ownership or creativity. New schools and genres of carving have arisen, reflecting the opening up of traditionally elite arts to a wider public in modern China. Qianshen uses an "iron brush" to etch ancient characters into stones selected for their subtle colors, textures, and markings. These small stone seals are inscribed with calligraphic characters or ancient symbols, a process he describes as "writing in stone." Often a person will use more than his or her given name, depending on the situation. For variety a name with a related meaning could be used, or a poetic name of one's home. Some people will also take a literary name, an epithet; and perhaps a studio name if they are artists. Qianshen has made a seal for his given name, one for his special name, and one with a studio name, which is "Cloud Studio - I wish I could be a white cloud floating in the sky so freely."

The production of seals requires a delicate calligraphic skill, as the stones are carved with script characters or similar pictorial figures like Qianshen's "auspicious bird." Another seal carries the common greeting "good luck". "In ancient China the character for sheep means good luck, because the sheep was the animal for sacrifice in worship of ancestors...this sacrifice will bring them good luck." The design is etched into the end of the seal stone with a small chisel, an "iron brush," in mirror image because when impressed it will be normal. Sometimes the character is positive, raised, and sometimes sunken for a white impression. To print, the seal is pressed into a cinnabar (sulphide of mercury) and oil paste.

When he was a doctoral candidate in Chinese art history at Yale University in the mid-1990s, Qianshen practiced both calligraphy and seal carving. In 1992, he co-organized an exhibit at the Yale Art Gallery entitled "The World Within a Square Inch: The Art of Chinese Seal Carving." He also developed an exhibit of Chinese calligraphers working in the last decade of the 20th century. Qianshen became Associate Professor of Art History at Boston University where in 2007 and 2013 he received grants to teach apprentice the elements of calligraphy under the Massachusetts Cultural Council’s Folk Arts Program.

Person TypeIndividual

American, founded 1881

American, 1793 - 1815