Exhibit Display: Polonia w Connecticut: Polish American Traditional Arts

Date2000-2001 December-March

MediumPositive color film slides

ClassificationsGraphics

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

CopyrightIn Copyright

Object number2015.196.1063.1-.20

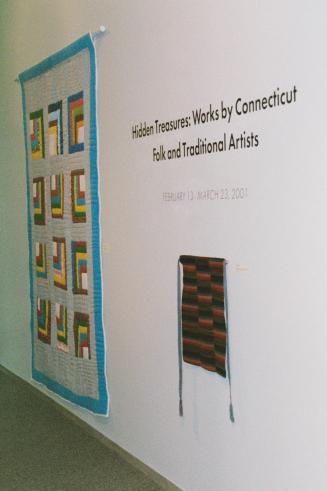

DescriptionSlide photographs of the installation of several sections of the "Polonia w Connecticut: Polish American Traditional Arts" exhibition at the Institute for Community Research.

(.1) Harvest ornaments from Bristol, Bridgeport, New Britain, and Hartford that have been used in Dożynki Harvest Festivals there.

(.2) Icons written by Marek Czarnecki.

(.3) The "Home" section of the exhibit.

(.4) Dance costumes displayed in the "Music and Dance" section of the exhibit.

(.5) The "Christmas and Wigilia" section of the exhibit.

(.6-.7) Szopki.

(.8) View of the "Home" and "Religion" sections of the exhibit.

(.9) A large modern Icon of Our Lady of Częstachowa, an assemblage made from sand, paste jewels, rhinestones, brooches, beads, glitter, and acrylic paint

by parishioners of St. Stanislaus Kostka Church in Waterbury, where it was venerated. It was loaned by the Church for the exhibit.

(.10-.11) Views of sections of the exhibit.

(.12) Processional and parade banners.

(.13) Embroideries and house blessings in the "Home" section.

(.14) The "Christmas and Wigilia" section of the exhibit.

(.15) Cradle made by Wladyslaw Furtak.

(.16) Introductory panel, szopka, and depictions of the White Eagle symbol of Poland made in embroidery and wycinanka.

(.17) The Easter Table assembled by Maria Brodowicz and Jadwiga Czarnecka.

(.18) Folk art pieces including wycinanki and embroideries in the "Home" section

(.19) Folk art pieces in the "Home" section.

(.20) The Easter Table assembled by Maria Brodowicz and Jadwiga Czarnecka, with a lamb cake and butter lamb mold, Easter wands, palm weavings, and pisanki.

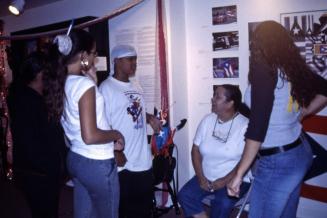

NotesSubject Note: "Polonia w Connecticut: Polish American Traditional Arts in Connecticut," an exhibition describing the arts and customs of this large community in Connecticut, was developed by CCHAP in collaboration with members of the Polish community, and was displayed in the gallery of the Institute for Community Research (ICR) from December 7, 2000 to May 2001. The project aimed to bring forward the enduring traditions of Polish American communities in Connecticut by conducting fieldwork in these communities, by collecting art works which express community traditions which still are practiced, by presenting an exhibition and related programming to the public and for schoolchildren, and by developing closer ties with the Polish community as ICR was situated in the heart of Hartford’s historic Polish neighborhood. Project partners included the Polish National Home, Ss. Cyril and Methodius Church and School, the Polish Cultural Club of Greater Hartford, the Polish Studies Department at Central Connecticut State University, and a number of community-based local Polish artists and collectors. Marek Czarnecki, an accomplished Byzantine iconographer and scholar from the Bristol Polish community, served as co-curator and gave a gallery talk on March 3, 2001. The project produced a catalogue of exhibit texts and information in both English and Polish. At the exhibit opening, performances were given by the Gwiazdeczki Dancers, a longstanding folk dance group from Saints Cyril and Methodius School and Parish, Hartford, and Wladyslaw Furtak, a singer, storyteller and woodcarver from the Gorale region of Poland who resides in Ansonia. Project funders included the Edward T. and Ann C. Roberts Foundation, the Connecticut Commission on the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Polish Studies Dept. of CCSU. (.1) Harvest ornaments from Bristol, Bridgeport, New Britain, and Hartford that have been used in Dożynki Harvest Festivals there.

(.2) Icons written by Marek Czarnecki.

(.3) The "Home" section of the exhibit.

(.4) Dance costumes displayed in the "Music and Dance" section of the exhibit.

(.5) The "Christmas and Wigilia" section of the exhibit.

(.6-.7) Szopki.

(.8) View of the "Home" and "Religion" sections of the exhibit.

(.9) A large modern Icon of Our Lady of Częstachowa, an assemblage made from sand, paste jewels, rhinestones, brooches, beads, glitter, and acrylic paint

by parishioners of St. Stanislaus Kostka Church in Waterbury, where it was venerated. It was loaned by the Church for the exhibit.

(.10-.11) Views of sections of the exhibit.

(.12) Processional and parade banners.

(.13) Embroideries and house blessings in the "Home" section.

(.14) The "Christmas and Wigilia" section of the exhibit.

(.15) Cradle made by Wladyslaw Furtak.

(.16) Introductory panel, szopka, and depictions of the White Eagle symbol of Poland made in embroidery and wycinanka.

(.17) The Easter Table assembled by Maria Brodowicz and Jadwiga Czarnecka.

(.18) Folk art pieces including wycinanki and embroideries in the "Home" section

(.19) Folk art pieces in the "Home" section.

(.20) The Easter Table assembled by Maria Brodowicz and Jadwiga Czarnecka, with a lamb cake and butter lamb mold, Easter wands, palm weavings, and pisanki.

The exhibit was timed to coincide with the annual "szopka contest" in late November when students from schools in New Britain and Hartford would create szopki - traditional Polish nativity scenes - then bring them to Hartford's Polish National Home on Charter Oak Avenue where a panel of judges awards prizes for excellence and creativity during the annual szopka festival. Some of these szopki were included in the CCHAP exhibit. Traditional art forms such as papercutting (wycinanki), painted eggs (pisanki), icons, embroidery, harvest ornaments, Christmas ornaments, and folk costumes all made by Connecticut Poles were featured, and the exhibit also included handmade altars and figures made for devotional use in people's homes, a common Polish practice. The exhibit demonstrated the beauty, usefulness, and continuation of traditional arts specific to the large Polish-American community in Connecticut, while also noting the ways traditions become altered in a new world setting.

Artists whose work was displayed in the exhibit included Maria Brodowicz, Jadwiga Czarnecka, Marek Czarnecki, Ursula Brodowicz, Carol Gregoire, Wladyslaw Furtak, Sophie Metrofski, and more. Many folk art pieces were donated to the exhibit by Bernard Pajewski.

Subject Note: The Polish community comprises nearly 10% of the state’s population, settling here during the late 19th and early 20th centuries when New England’s industrial growth made jobs plentiful in mills and factories. Thousands from rural areas of Poland left behind difficult political and economic circumstances to work in America. A similar movement of people took place in the 1980s, and Polish newcomers continue to arrive, bringing a very different sense of “Polishness” and cultural tastes from the older immigrants. Uprooted from their homeland and all that is familiar, these new Americans have found refuge in maintaining traditional customs, beliefs, foods, language, and joining together in fraternal, cultural, political, academic, and veterans societies. Parish churches fill a very important function as centers for social organization and cultural unity as well as providing spiritual and emotional comfort. The Polish saying Co kraj, to obyczaj explains that in the American Polish communities called Polonia some of the old practices change to fit new circumstances, or disappear altogether among recent generations.

The seasonal round of celebrations, festivals, holidays, along with the activities and art forms associated with them, connect Polish Americans to a dimension of beauty, meaning, spirituality, and heritage which they remember from the past but also practice today. In Connecticut works of art and everyday objects for use in the home are still made by hand in traditional Polish styles. Older objects from Poland are often redecorated with materials found here, and the process of creating and using these pieces shows an active expression of identity, not a mere recreation of old folk art forms.

New Britain, the center of Polonia in Connecticut, has a longstanding language school and folk dance group. Central Connecticut State University hosts the Polish and Polish American Studies Program and Library – one of only two such programs in the country. Broad Street is a thriving center of Polish commerce and activity, and has hosted an annual festival since 2012 called “Little Poland.” The festival is held in late April to mark Poland’s Constitution Day, a celebration of the democracy enjoyed by Americans under their country’s Constitution. In Hartford, the historically Polish neighborhood around Wyllys St/Popieluszko Court/Charter Oak Avenue included SS Cyril and Methodius Church, the Church School, the Polish National Home, and several businesses.

Community celebrations and seasonal holidays often follow the liturgical calendar of the Church. Christmas is celebrated with Pasterka, the midnight mass of the shepherds when koledy, holy carols, are sung. On the Feast of Epiphany, chalk is blessed in the church and used to inscribe door lintels with K + M + B, the initials of the three kings. At Easter, baskets of food for the Easter breakfast are blessed in the church. Processions mark Corpus Christi, the Feast of the Blessed Sacrament (and a ritual to ensure good crops) in June. In the late summer, harvest festivals called Dożynki featuring an open-air or church Mass with a blessing and distribution of bread, folk dancing, craft and food vendors are held in New Britain, Bristol, and Bridgeport/Ansonia. Harvest ornaments, large structures of wheat sheafs decorated with flowers and ribbons, are made and displayed by community artists. On All Souls Day in November Polish families visit the graves of their relatives, decorating them with candles and flowers after an outdoor mass.

One of the Polish community’s important artists, iconographer Marek Czarnecki from Bristol “writes” images of saints that convey essential theological and biographical information and embody the presence of the holy ones depicted. A respected community scholar and teacher, he also restores church statues and lectures on Polish folk traditions such as szopka-making.

Subject Note: Harvest festivals, Dożynki, were once common in the agricultural regions of Poland. The harvesting of grain for bread was crucial to survival, and many customs in rural Poland were designed to encourage a good crop. As with so many Polish celebrations, spiritual and secular worlds and concerns intertwine at this important time of year. Harvest time in late summer coincided with the religious Feast of the Assumption on August 15, celebrating the ascension of Mary into Heaven. On this feast day called Matka Boska Zielna, or Our Lady of the Herbs, women brought bouquets of herbs and flowers to the church to be blessed so that the healing powers of the plants would strengthen. At home they would place sprigs of herbs behind holy pictures on the wall. Flowers, herbs, and sheaves of wheat and rye were made into ornaments for dożynki celebrations. Some of these were large and heavy, symbolizing an abundant harvest, and some were shaped to suggest figures or topped with religious statues. Those involved in the harvest also fashioned dożynki wreaths in the shape of a crown out of grains, flowers, nuts, fruit, and ribbons. A young girl who had worked on the harvest would wear the wreath in procession to the house of the farmer, to whom the wreath would be presented.

In Connecticut several Polish American communities still hold dożynki festivals even though most people live and work in urban or suburban settings rather than on farms. The purpose of dożynki in Polonia is to reinstill an understanding of “Polishness” through using ceremony, music, and objects and values reminiscent of customs from Poland. For nineteen years New Britain has produced a festival featuring an open-air mass with a blessing and distribution of bread, folk dancing, craft and food vendors. Other communities holding annual harvest masses and festivals include Bristol’s St. Stanislaus Kostka Church and parish, and in Bridgeport/Ansonia at the White Eagle Social Club. Elaborate dożynki ornaments are still made and carried into the church during the festivals. While contemporary dożynki celebrations tend to be socials and parish fundraisers rather than agricultural rituals, they retain a strong sense of the way spirituality affects the daily lives of Polish Americans.

Subject Note: Wigilia/Christmas Eve Traditions - The most important holiday of the year, Wigilia marks a time of watching for the birth of Jesus. The weeks of Advent just before and the Wigilia customs themselves focus on setting things in order, following good behavior and being ready and worthy for the gift of the Savior. During the day, people observe a fast; then at the appearance of the first star in the evening sky, families gather for the Christmas Eve supper. Hay is placed under the tablecloth, and often a place is set in anticipation of the Christ child or for an unexpected guest. Opłatek, thin wafers embossed with pictures of the nativity scene and blessed in the church, are broken and shared among everyone at the table. As the head of the household hands one to each person, a greeting such as this is given: "Nie Bóg daj rok doczekacz - May God grant you another year." Sharing opłatek represents the heart of this holiday, when wrongs or bad feelings between people are rectified and positive hopes for the future restored. Wafers are sent to distant relatives and even offered to animals, as they were the first creatures to offer hospitality to Christ. After the opłatek ceremony, an odd number of meatless dishes are served, representing the harvests of fields, gardens, woods, rivers, and orchards. The family sings traditional carols, kołędy, then attends midnight mass, called Pasterka, the shepherds’ mass.

Wigilia traditions persist strongly in Polonia, probably because of their intensely spiritual meaning and the important concepts of reconciliation and salvation that underlie the rituals. The power of this holiday derives from its sense of community and fellowship - every Polish person is celebrating in the same way all over the world. In addition to family Wigilias on Christmas Eve, Polish churches, clubs, and societies hold communal Wigilias and carol singing for their members. The Polish Cultural Club of Greater Hartford has its Wigilia supper this year on December 8. Polish Americans decorate their homes with traditional ornaments made from straw, paper, tin foil, beads, and eggs in the shape of stars or “spiders”, and place these on their Christmas trees.

Subject Note: Święta Wielkanocne/Easter Traditions - As the liturgical calendar year continues after Christmas, Catholics observe the forty days of Lent, a representation of the time of Christ’s suffering. For Poles, reflection, prayer, and strict fasting during Lent is preceded by Tłusty Czwartek, Fat Thursday, when Polish Americans traditionally eat pączki, doughnuts filled with fruit jelly or cream. In Connecticut and Massachusetts Big Y Supermarkets promote pączki extensively during the short time in February when the stores make them. After Ash Wednesday, churches hold a Lenten evening service called Gorzkie Zale, during which sorrowful hymns are sung as a meditation on the passion and death of Christ. As Lent draws to its end, Palm Sunday is marked by woven and braided ornaments of palms representing those carried by well wishers along the route of Christ’s procession through the streets of Jerusalem. Another sign of Easter and the renewal of spring can be seen in the wands made of flowers, straw, colored paper, and pussy willows. Because no church bells ring until Easter Sunday, boys call attention to church services by shaking klekotki, wooden clappers. In a custom unique to Polish churches, a recreation of Christ’s grave is built near the altar; parishioners hold a vigil by the grave, bringing flowers and praying.

Easter itself continues to be an extremely important spiritual celebration in Polonia. Symbols of renewal, resurrection, and new life from both spiritual and agricultural worlds appear everywhere in Easter customs. Polish Americans bring baskets of food to the church on Saturday to be blessed by the priest who sprinkles holy water on them. The baskets are taken home and eaten at the Easter breakfast, święconka, which takes place after the sunrise mass, rezurekcja, and its procession. Easter foods include ham or kielbasa; a sweet bread called babka and a round bread with a cross; butter molded into the shape of a lamb and sugar lambs, symbolizing the sacrifice of Christ; and a horseradish relish which denotes the bitterness of Christ’s suffering. Most significant of all the Easter foods, an egg is divided among all those present at the Easter breakfast table as a symbol of unity, the mystery of life, and fertility. One of the best known Polish traditional arts is pisanki, decorative eggs colored originally with onion skins and other vegetable dyes. Different regional designs of lines, dots, flowers, or hearts are “written” in wax on the eggs with pins; some eggs are decorated with yarn and paper cuttings. As they do with wigilia dinners, many community organizations throughout Polonia hold social święconka for members and those whose families are far away.

Additional materials exist in the CCHAP archive for this artist and these activities.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.

Status

Not on viewJampa Tsondue

2018 March 10

Glaisma Pérez Silva

July 1999

Haris Gusta Guya

2011 November 4

Ilka Robles

June-August 2003