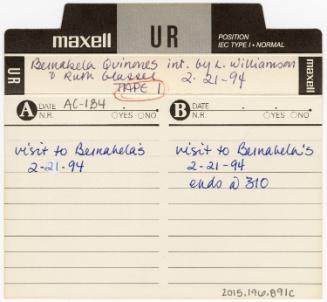

Mundillo Lacemaking by Bernabela Quiñones

SubjectPortrait of

Bernabela Quiñones

(Puerto Rican, born 1900)

SubjectPortrait of

Ruth Glasser

(American)

PhotographerPhotographed by

Gale Zucker

DateFebruary 1994

Mediumphotographic prints

ClassificationsGraphics

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

CopyrightIn Copyright

Object number2015.196.1015.1-.12

DescriptionPhotographs taken by Gale Zucker for the second Living Legends Project showing Bernabela Quiñones making lace. The photographs were taken in Bernabela Quiñones' home in Waterbury, Connecticut in February 1994.

(.1-.3) Bernabela Quiñones making lace on her mundillo pillow loom.

(.4) Finished lace pieces made by Bernabela Quiñones.

(.5) Bernabela holds a finished lace piece.

(.6-.12) Bernabela Quiñones making lace on her mundillo pillow loom as Ruth Glasser looks on.

NotesBiographical Note: Bernabela Quiñones (Lace Making) was a 94 year old Puerto Rican woman living in Waterbury, Connecticut at the time of the Living Legends Project in 1994. For many years she supported her family by selling her lace work in the Moca area of Puerto Rico, long famous for its textile artists, an endangered art form. Program Director Lynne Williamson and Ruth Glasser, a consultant ethnomusicologist working with the Puerto Rican community in Waterbury, interviewed Senora Quiñones on tape. She described and demonstrated her loom lace making, which she continued as a way to pass the time and to create lace socks for her grandchildren and greatgrandchildren. (.1-.3) Bernabela Quiñones making lace on her mundillo pillow loom.

(.4) Finished lace pieces made by Bernabela Quiñones.

(.5) Bernabela holds a finished lace piece.

(.6-.12) Bernabela Quiñones making lace on her mundillo pillow loom as Ruth Glasser looks on.

The Aguadilla area of northwest Puerto Rico is the home of a lacemaking tradition brought to the island by Spanish nuns. Traditional Puerto Rican lace is made on a small loom called mundillo, because it has a rotating pillow-shaped drum. Doña Bernabela, born February 25, 1900, in the town of Moca near Aguadilla, was still making lace in her Waterbury apartment up until about 1996. When CCHAP visited her in 1994, she stood at her loom, needing glasses only for this activity, continuing to weave lace for occasional sale through an artists' cooperative in Puerto Rico and as gifts to family and friends.

"Eso es lo que nosotros hacíamos antes...ganabamos dinero. Todas las muchachas campesinas...(tenian que caminar) ocho kilometros de camino para buscar trabajo...Esos trajes eran preciosos." (That's what we did to earn money. All the farm girls did it, had to walk 8 miles to look for work. Some of those clothes were beautiful.)

One of seven children in a rural family, Doña Bernabela remembered many stories about her early life. Her father cultivated sugar cane and worked in the mill grinding the cane and tending the fire. The family kept horses, oxen, cows, goats on the farm; they would gather herbs for headaches and other ailments. Because there was so much work to do, she had to leave school in the fourth grade to help. "Mucho sudor, mucho sudor. Uno cogía el machete ...a picar palos en el monte." (A lot of sweat, a lot of sweat. One took a machete...to cut down trees in the hills, for firewood). There were no newspapers, so when a hurricane was coming a man would run barefoot from San Sebastian, Arecibo, or Isabela to warn people, although Bernabela's mother, who was of mixed Indian and white heritage, would also know by the way leaves of a certain tree "turned inside out." Her brother played guitar and cuatro, and they would hold dances in their house.

Lace making was taught to girls in school as early as second grade. When Doña Bernabela left school her older sister, a seamstress, continued to teach her a variety of sewing and embroidery techniques. "Tienes que echar tiempo mirando." (You have to spend time watching.) A common source of income for rural women, lace making and embroidery were also taught through apprenticeships at workshops and factories in the towns. "Yo iba a Agüadilla cada 15 días...a llevar tejido...Una caja." (I went to Aguadilla every two weeks...to get the lace...a boxful." Factories would open at 8:30 a.m., and those not already sewing inside would line up to receive jobs to be taken home. After finishing the orders, the girls would walk back to deliver and pick up another batch. "La paga era muy poca." (They paid very cheaply.) The piecework was sold by the factories to merchants who either exported it to the United States or sold it in San Juan shops.

All kinds of fine sewing and textile embellishments were done by island women. Doña Bernabela spoke about making lace baby booties, children's caps, handkerchiefs, pillowcases, petticoats, and yard-long lengths. She was also skilled at embroidery, doing piecework on smoking jackets and children's clothes, specialized needlework techniques such as puntada, calado (openwork), buchipluma, and appliqué, in addition to making gloves and hats. "Antes de soltera cualquier cosa yo hacía." (When I was single I would make anything.)

After her marriage to a foreman in a sugar mill, Doña Bernabela had to put aside lace making to raise her four children and tend the farm. Sometimes she sewed at night to earn money for the family during the "tiempo muerto," the months between sugar harvest and planting, and after her husband became ill and could no longer work. In 1959, she moved to Waterbury to live near her son, supporting herself by washing, cleaning, and cooking for other people. When her husband died in 1975, Doña Bernabela began to make lace again.

Traditional Puerto Rican lace is made on a small loom called mundillo, because it has a rotating pillow-shaped drum. A paper pattern is held in place on the pillow with hundreds of pins marking the design. Thread carried on as many as fifty wooden bobbins (called bolillos) is woven around the pins to make the intricate designs take shape. When we visited her home, Doña Bernabela worked with four bobbins at a time, grabbing one and passing it over the others. At this time she was making baby booties and caps, taking about a week to do a set despite considerable pain in her arm from arthritis.

"Antes aprendían en casa...Hay que poner atencion, poner la cabeza...Antes nosotros en la casa enseñabamos a las muchachitas. Y muchas muchachitas enseñaban a nosotras a tejer...A casa iban unas cuantas muchachas..." (They used to learn in the house...You have to pay attention, put your head to it. We used to show the young girls in our house. And many young girls showed us how to make lace...Many girls came to the house (to learn).)

"Cuando yo estaba en la escuela...cuando entre al segundo grado...en el '11 yo aprendí a hacer estas cosas. En Moca era el pueblo donde abundába eso. En Moca trabajaban todas las muchachas, mucha gente corrían pa'llá y pa'cá tejiendo, bordando, cosiendo. Yo bordaba, yo cosia, yo hacía pañuelos...de todo. Y también cosía a mano. Y entonces yo bordaba con hilo blanco...al realce." (When I was in school...when I entered second grade...in '11 I learned how to do those things. Moca was the town where this work abounded. In Moca all the girls worked, a lot of people running here and there making lace, embroidering, sewing. I embroidered, I sewed, I made handkerchiefs...everything. And I also sewed by hand. And I embroidered with white thread...raised work.)

"Una hacia ese trabajo por el dia y por la noche. Y no habia eso de electricidad, era gas." (One did this work day and night. And there wasn't electricity, it was gas.)

Subject Note: Living Legends: Connecticut Master Traditional Artists was a multi-year project to showcase the excellence and diversity of folk artists living and practicing traditional arts throughout the state. The first CCHAP Director, Rebecca Joseph, developed the first exhibition in 1991, displaying photographic portraits along with art works and performances representing 15 artists from different communities at the Institute for Community Gallery at 999 Asylum Avenue in Hartford. In 1993, the next CCHAP Director, Lynne Williamson, organized two exhibitions of the photographic portraits from the original Living Legends exhibit at the State Legislative Offices and at Capital Community-Technical College in Hartford. The photographs were also displayed in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, DC in October 1994, with the help of Rep. Nancy Johnson. Also in 1993, a grant from NEA Folk Arts was awarded to CCHAP to expand and tour the original exhibit and create a video to accompany it. The Connecticut Humanities Council and the Connecticut Commission on the Arts supported an exhibit catalogue and a performance series. CCHAP began fieldwork around the state in 1994 to document several of the artists involved in the first exhibit, adding new artists. The expanded version of Living Legends opened at ICR's Gallery at its new office space at 2 Hartford Square West, then traveled to several sites in 1994 and 1995, including the Norwich Arts Council, the Torrington Historical Society, and the New England Folklife Center, Boott Mills Museum at Lowell National Historical Park in Lowell Massachusetts. CCHAP along with folklorist David Shuldiner created a video based on images taken of the artists at work and interviews conducted with them. Portraits and images of the artists working were taken by photographer Gale Zucker. A catalogue of the images, art works, and texts based on the artist interviews was compiled by CCHAP and designed by Dan Mayer who also served as the exhibition designer.

Thirteen visual artists were included in the new Living Legends project: Eldrid Arntzen, Norwegian rosemaling; Qianshen Bai, Chinese seal carving; Katrina Benneck, German scherenschnitt; Alice Brend, Pequot ash basket making; Romulo Chanduvi, Peruvian wood carving; Laura Hudson, African American quilt making; Ilias Kementzides, Pontian Greek lyra making and playing; Sotha Keth and Sophanna Keth Yos, Cambodian dance costume making; Keith Mueller, decoy carving; Bernabela Quiñones, Puerto Rican mundillo lace; Walter Scadden, decorative ironwork; Nucu Stan, Romanian straw pictures. Five performing artists were presented: Sonal Vora, Indian Odissi dance; Somaly Hay, Cambodian court dance; Ilias Kementzides, Pontian Greek lyra; Abraham Adzenyah, Ghanaian music and drumming; and La Primera Orquesta de Cuatros, Puerto Rican cuatro group.

The profound way these artists describe their inspirations, their intricate technical processes, and the dynamic tension they feel between traditional form and personal innovation within that form mark them as true creative masters. The artists featured in Living Legends had very different characters, stories, homelands, communities, art forms and techniques, but they were linked by their high level of artistic skill and a devotion to the traditions of their culture. The Living Legends project highlighted the way that cultural histories, technical information, aesthetic tastes, social values and other deep aspects of heritage can be communicated through the process and creation of traditional arts. Also, these artists express a strong desire to teach what they know to others, to "pass on the tradition." Community survival, memories of the past, and hopes for the next generation depend on exemplary culture bearers such as these.

Biographical Note: Gale Zucker is an experienced professional photographer and artist with a special interest in fiber arts. Her photojournalism has appeared in Forbes, Modern Maturity, Newsweek, the New York Times, and Yankee. She exhibits in Connecticut, New York, and New Hampshire and received a grant from the Minnesota Folklife Center to produce an audio-visual program. Her many commercial and arts-world clients include the National Endowment for the Arts, Modern Knitting, the Connecticut Health Foundation, Smithsonian Magazines, Penguin Random House, and Raytheon Technologies, among others. She collaborated with CCHAP on photography portraits and artists’ techniques/processes documentation for the Living Legends exhibit project from 1991-1994.

Biographical Note: Ruth Glasser, Professor in the Urban and Community Studies Department at the University of Connecticut, was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. She worked as a VISTA volunteer in North Carolina in 1979-1980. She has worked on a variety of academic and community-based endeavors including books, curriculum projects, oral history projects, and exhibits. Her publications include: "My Music is My Flag: Puerto Rican Musicians and Their New York Communities, 1917-1940" (University of California Press, 1995), "Aquí Me Quedo: Puerto Ricans in Connecticut" (Connecticut Humanities Council, 1997), "Aquí Me Quedo K-12 Curriculum Guide" (Mattatuck Museum, 1999), [as co-editor] "Caribbean Connections: Dominican Republic" (Teaching for Change, 2004). She assisted CCHAP with two projects: “Living Legends: Connecticut Master Traditional Artists,” interviewing Puerto Rican lace maker Bernabela Quiñones in 1994; and the “Herencia Taina: Legacy and Life” exhibition project in 1997.

Additional materials exist in the CCHAP archive for this artist and this project.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.

Status

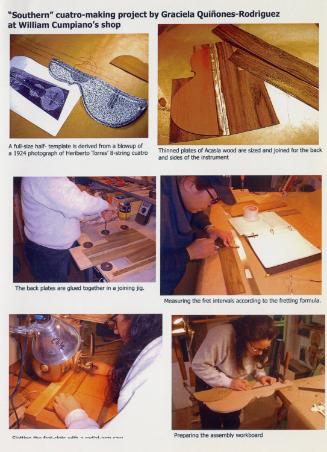

Not on viewGraciela Quiñones-Rodriguez

2004 February 21