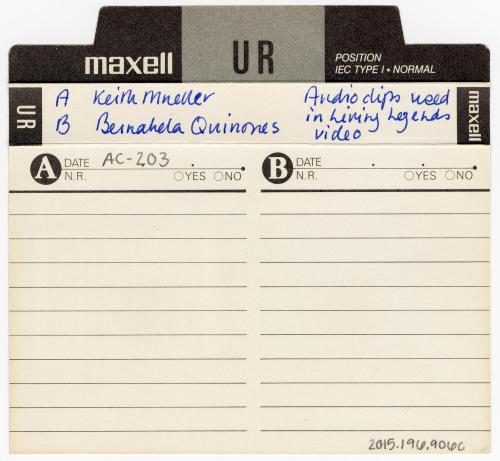

Living Legends Project: Keith Mueller and Bernabela Quinones Interview Clips

PerformerPerformed by

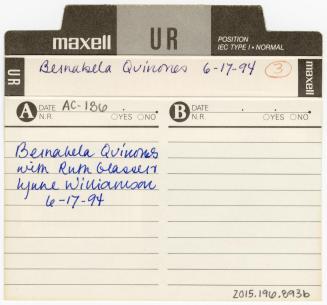

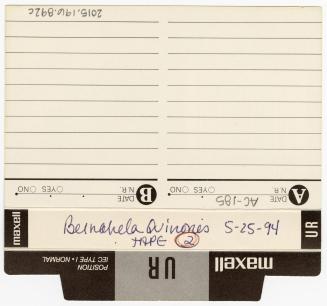

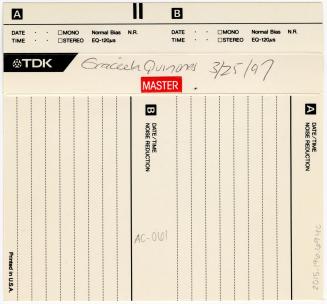

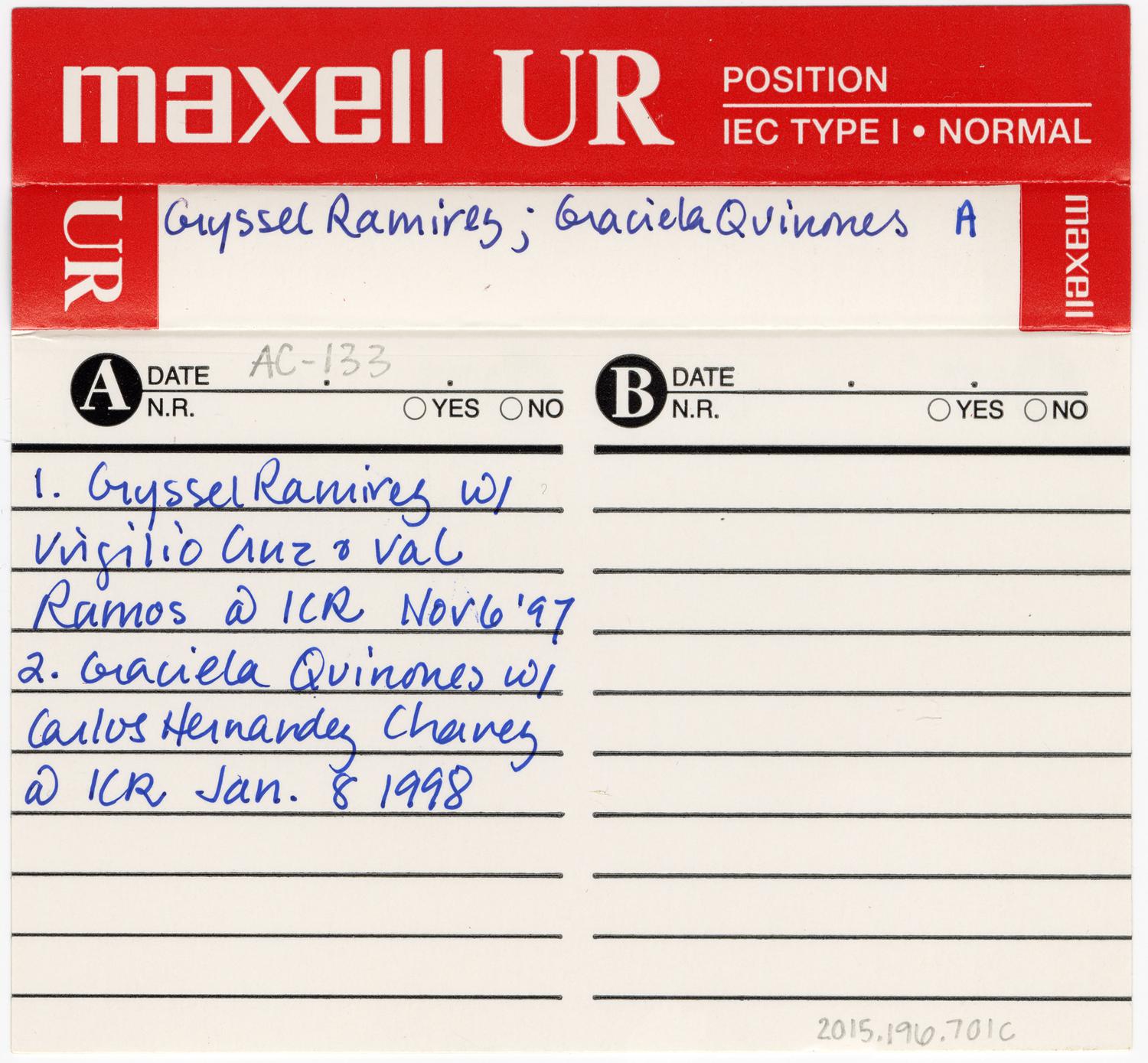

Bernabela Quiñones

(Puerto Rican, born 1900)

Date1994

Mediumreformatted digital file from audio cassette

DimensionsDuration (side 1): 27 Minutes, 49 Seconds

Duration (side 2): 30 Minutes, 2 Seconds

Duration (total runtime): 57 Minutes, 57 Seconds

ClassificationsInformation Artifacts

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

CopyrightIn Copyright

Object number2015.196.906a-d

DescriptionAudio cassette tape recording with interview clips of Bernabela Quiñones and Keith Mueller to be used for the background audio track for the Living Legends exhibit video.

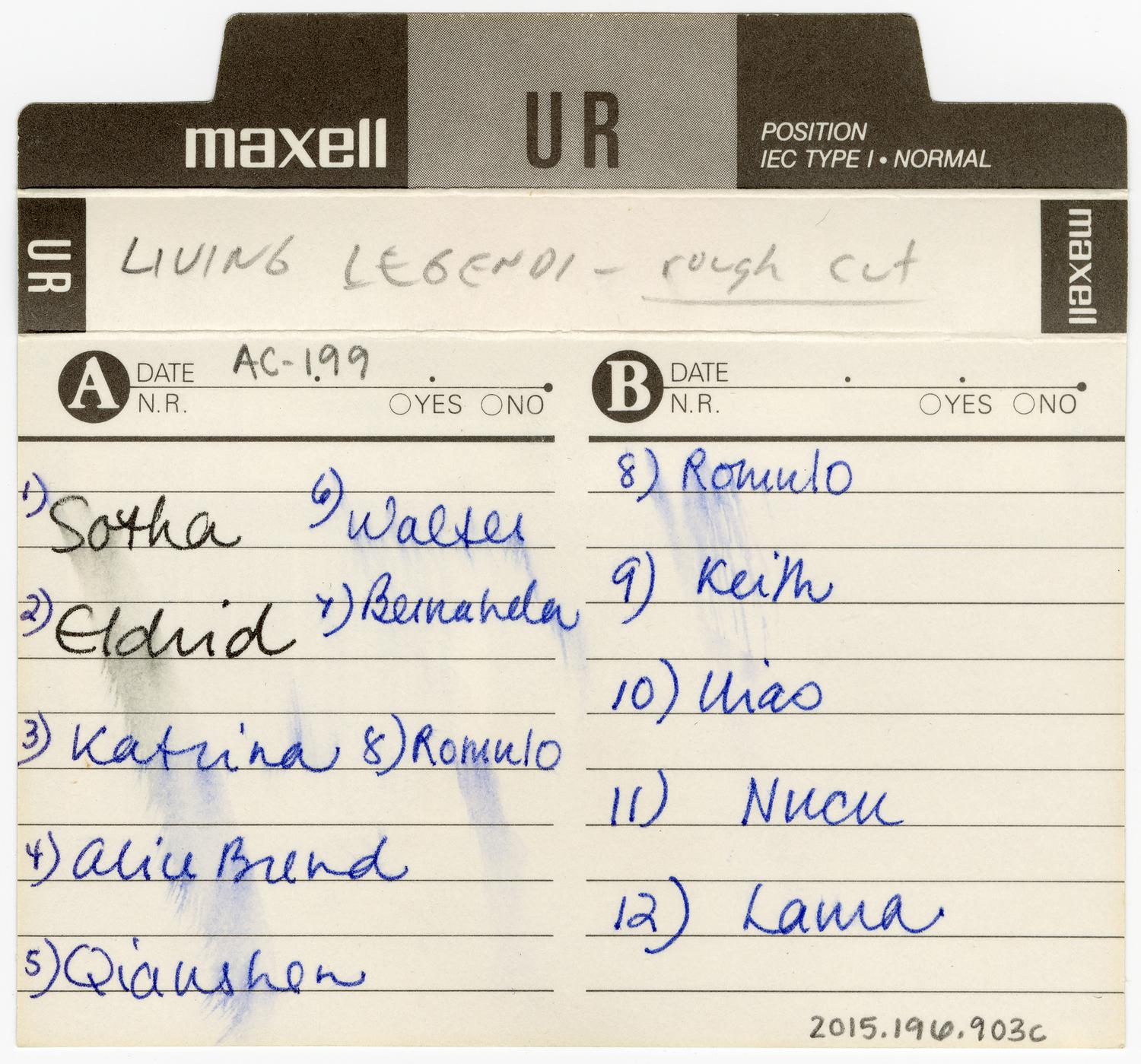

NotesSubject Note: Living Legends: Connecticut Master Traditional Artists was a multi-year project to showcase the excellence and diversity of folk artists living and practicing traditional arts throughout the state. The first CCHAP Director, Rebecca Joseph, developed the first exhibition in 1991, displaying photographic portraits along with art works and performances representing 15 artists from different communities, at the Institute for Community Gallery at 999 Asylum Avenue in Hartford. In 1993, the next CCHAP Director, Lynne Williamson, organized two exhibitions of the photographic portraits from the original Living Legends exhibit at the State Legislative Offices and at Capital Community-Technical College in Hartford. The photographs were also displayed in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, DC in October 1994, with the help of Rep. Nancy Johnson. Also in 1993, a grant from NEA Folk Arts was awarded to CCHAP to expand and tour the original exhibit and create a video to accompany it. The Connecticut Humanities Council and the Connecticut Commission on the Arts supported an exhibit catalogue and a performance series. CCHAP began fieldwork around the state in 1994 to document several of the artists involved in the first exhibit, adding new artists. The expanded version of Living Legends opened at ICR's Gallery at its new office space at 2 Hartford Square West, then traveled to several sites in 1994 and 1995, including the Norwich Arts Council, the Torrington Historical Society, and the New England Folklife Center, Boott Mills Museum at Lowell National Historical Park in Lowell Massachusetts. CCHAP along with folklorist David Shuldiner created a video based on images taken of the artists at work and interviews conducted with them. Portraits and images of the artists working were taken by photographer Gale Zucker. A catalogue of the images, art works, and texts based on the artist interviews was compiled by CCHAP and designed by Dan Mayer who also served as the exhibition designer.Thirteen visual artists were included in the new Living Legends project: Eldrid Arntzen, Norwegian rosemaling; Qianshen Bai, Chinese seal carving; Katrina Benneck, German scherenschnitt; Alice Brend, Pequot ash basket making; Romulo Chanduvi, Peruvian wood carving; Laura Hudson, African-American quilt making; Ilias Kementzides, Pontian Greek lyra making and playing; Sotha Keth and Sophanna Keth Yos, Cambodian dance costume making; Keith Mueller, decoy carving; Bernabela Quiñones, Puerto Rican mundillo lace; Walter Scadden, decorative ironwork; Nucu Stan, Romanian straw pictures. Five performing artists were presented: Sonal Vora, Indian Odissi dance; Somaly Hay, Cambodian court dance; Ilias Kementzides, Pontian Greek lyra; Abraham Adzenyah, Ghanaian music and drumming; and La Primera Orquesta de Cuatros, Puerto Rican cuatro group.

The profound way these artists describe their inspirations, their intricate technical processes, and the dynamic tension they feel between traditional form and personal innovation within that form mark them as true creative masters. The artists featured in Living Legends had very different characters, stories, homelands, communities, art forms and techniques, but they were linked by their high level of artistic skill and a devotion to the traditions of their culture. The Living Legends project highlighted the way that cultural histories, technical information, aesthetic tastes, social values and other deep aspects of heritage can be communicated through the process and creation of traditional arts. Also, these artists express a strong desire to teach what they know to others, to "pass on the tradition." Community survival, memories of the past, and hopes for the next generation depend on exemplary culture bearers such as these.

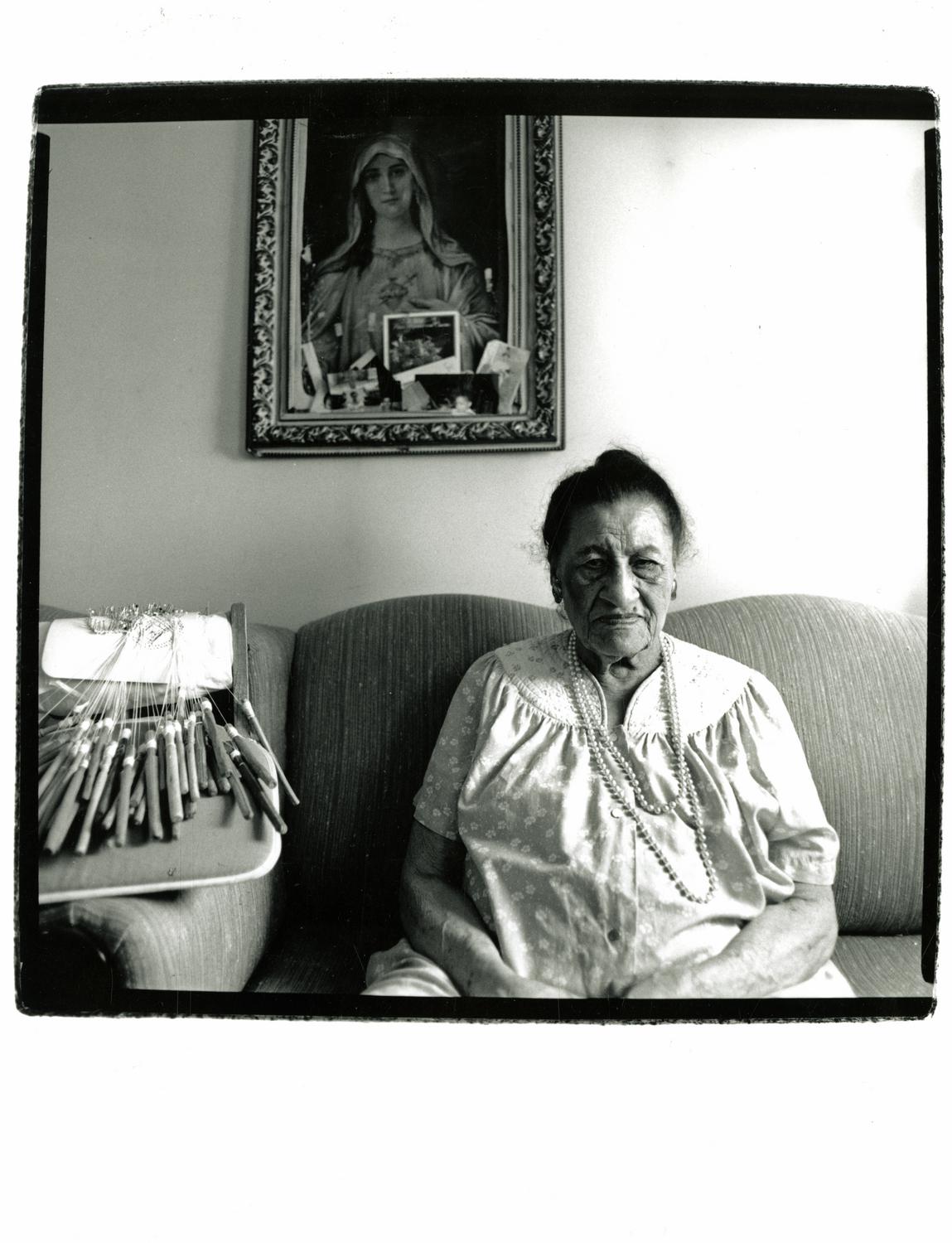

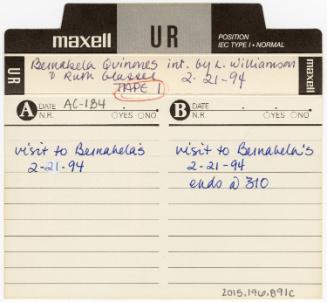

Bernabela Quinones (Lace Making) was a 94 year old Puerto Rican woman living in Waterbury, CT at the time of the Living Legends Project in 1994. For many years she supported her family by selling her lace work in the Moca area of Puerto Rico, long famous for its textile artists, an endangered art form. Program Director Lynne Williamson and Ruth Glasser, a consultant ethnomusicologist working with the Puerto Rican community in Waterbury, interviewed Senora Quinones on tape. She described and demonstrated her loom lace making, which she continued as a way to pass the time and to create lace socks for her grandchildren and greatgrandchildren.

The Aguadilla area of northwest Puerto Rico is the home of a lacemaking tradition brought to the island by Spanish nuns. Traditional Puerto Rican lace is made on a small loom called mundillo, because it has a rotating pillow-shaped drum. Doña Bernabela, born February 25, 1900 in the town of Moca near Aguadilla, was still making lace in her Waterbury apartment up until about 1996. When CCHAP visited her in 1994, she stood at her loom, needing glasses only for this activity, continuing to weave lace for occasional sale through an artists' cooperative in Puerto Rico and as gifts to family and friends.

"Eso es lo que nosotros hacíamos antes...ganabamos dinero. Todas las muchachas campesinas...(tenian que caminar) ocho kilometros de camino para buscar trabajo...Esos trajes eran preciosos." (That's what we did to earn money. All the farm girls did it, had to walk 8 miles to look for work. Some of those clothes were beautiful.)

One of seven children in a rural family, Doña Bernabela remembered many stories about her early life. Her father cultivated sugar cane and worked in the mill grinding the cane and tending the fire. The family kept horses, oxen, cows, goats on the farm; they would gather herbs for headaches and other ailments. Because there was so much work to do, she had to leave school in the fourth grade to help. "Mucho sudor, mucho sudor. Uno cogía el machete ...a picar palos en el monte." (A lot of sweat, a lot of sweat. One took a machete...to cut down trees in the hills, for firewood). There were no newspapers, so when a hurricane was coming a man would run barefoot from San Sebastian, Arecibo, or Isabela to warn people, although Bernabela's mother, who was of mixed Indian and white heritage, would also know by the way leaves of a certain tree "turned inside out." Her brother played guitar and cuatro, and they would hold dances in their house.

Lace making was taught to girls in school as early as second grade. When Doña Bernabela left school her older sister, a seamstress, continued to teach her a variety of sewing and embroidery techniques. "Tienes que echar tiempo mirando." (You have to spend time watching.) A common source of income for rural women, lace making and embroidery were also taught through apprenticeships at workshops and factories in the towns. "Yo iba a Agüadilla cada 15 días...a llevar tejido...Una caja." (I went to Aguadilla every two weeks...to get the lace...a boxful." Factories would open at 8:30 a.m., and those not already sewing inside would line up to receive jobs to be taken home. After finishing the orders, the girls would walk back to deliver and pick up another batch. "La paga era muy poca." (They paid very cheaply.) The piecework was sold by the factories to merchants who either exported it to the U.S. or sold it in San Juan shops.

All kinds of fine sewing and textile embellishments were done by island women. Doña Bernabela spoke about making lace baby booties, children's caps, handkerchiefs, pillowcases, petticoats, and yard-long lengths. She was also skilled at embroidery, doing piecework on smoking jackets and children's clothes, specialized needlework techniques such as puntada, calado (openwork), buchipluma, and appliqué, in addition to making gloves and hats. "Antes de soltera cualquier cosa yo hacía." (When I was single I would make anything.)

After her marriage to a foreman in a sugar mill, Doña Bernabela had to put aside lace making to raise her four children and tend the farm. Sometimes she sewed at night to earn money for the family during the "tiempo muerto," the months between sugar harvest and planting, and after her husband became ill and could no longer work. In 1959 she moved to Waterbury to live near her son, supporting herself by washing, cleaning, and cooking for other people. When her husband died in 1975, Doña Bernabela began to make lace again.

Traditional Puerto Rican lace is made on a small loom called mundillo, because it has a rotating pillow-shaped drum. A paper pattern is held in place on the pillow with hundreds of pins marking the design. Thread carried on as many as fifty wooden bobbins (called bolillos) is woven around the pins to make the intricate designs take shape. When we visited her home, Doña Bernabela worked with four bobbins at a time, grabbing one and passing it over the others. At this time she was making baby booties and caps, taking about a week to do a set despite considerable pain in her arm from arthritis.

"Antes aprendían en casa...Hay que poner atencion, poner la cabeza...Antes nosotros en la casa enseñabamos a las muchachitas. Y muchas muchachitas enseñaban a nosotras a tejer...A casa iban unas cuantas muchachas..." (They used to learn in the house...You have to pay attention, put your head to it. We used to show the young girls in our house. And many young girls showed us how to make lace...Many girls came to the house (to learn).)

"Cuando yo estaba en la escuela...cuando entre al segundo grado...en el '11 yo aprendí a hacer estas cosas. En Moca era el pueblo donde abundába eso. En Moca trabajaban todas las muchachas, mucha gente corrían pa'llá y pa'cá tejiendo, bordando, cosiendo. Yo bordaba, yo cosia, yo hacía pañuelos...de todo. Y también cosía a mano. Y entonces yo bordaba con hilo blanco...al realce." (When I was in school...when I entered second grade...in '11 I learned how to do those things. Moca was the town where this work abounded. In Moca all the girls worked, a lot of people running here and there making lace, embroidering, sewing. I embroidered, I sewed, I made handkerchiefs...everything. And I also sewed by hand. And I embroidered with white thread...raised work.)

"Una hacia ese trabajo por el dia y por la noche. Y no habia eso de electricidad, era gas." (One did this work day and night. And there wasn't electricity, it was gas.)

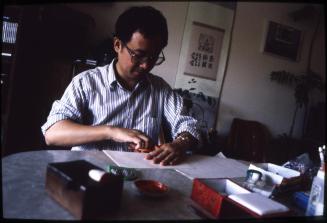

Biographical Note: Keith Mueller carves traditional New England sea duck decoys that he actually uses in hunting. A self-taught expert in waterfowl anatomy, Keith has compiled an illustrated guide to the ecosystems, feeding habits, and anatomical structure of the birds he loves, based on years of first-hand observation. "Form and function are what I'm trying to get across...you draw what you witness, break down your observations...The best thing of all these years of carving is the research I'm doing. It will affect my carving tremendously." In addition to the working decoys, Keith has perfected his skill in carving and painting realistic birds. He is a multi-year winner of the World Championship in the Hunting Decoy Division and several other divisions at the Ward Foundation annual competition in Ocean City, Maryland.

The traditional decoys hold great interest for Keith, because a long line of carvers designed, refined and tested them for a purpose. Early decoy forms have simple, almost stylized lines. They are painted to suggest the species of duck but do not need to depict plumage realistically. The point is to carve a form which will attract other ducks. "The decoys are there to lure the ducks to you. They fly by and see the decoys and they're curious...you rig them all on a line and anchor them to the bottom...the formation looks natural because eiders fall into strings when they feed...eiders fly low so sometimes the decoys end up getting shot." Keith notes that eider ducks have patches of luminous green on their neck, however "on the old birds you don't put the green...that's the color of the bird but the paint was not around to use that color on the decoys - it wasn't practical, wasn't functional." Keith learned much about the process of carving decoys from hunters he met in his early years. They instructed him, sometimes none too gently, in the strict rules of hunting as well as functional carving. He was taught how to use waterproof glues and oil-based paints rather than acrylics, about types of wood and where to find them, and about the questionable benefits of finishing and sanding. "I have a friend named Paul Sheridan, he knew some of the famous Connecticut decoy makers...he still carved right up until recently, fashioned old decoys as a functional tool...they look rough but they work. Another one was Ted Mulligan who owned a decoy factory in Old Saybrook that burned down in the 50's."

Keith describes the history of Connecticut decoy carving: "The original Connecticut decoys were patterned after a man who moved to New Jersey, Albert Lang, who started to adapt his own style - this is back in the late 1800's. He fashioned them a little bit different to be functional in this area. The next person would be Ben Holmes and he continued that style but added a little more flair to it...Then came Shang Wheeler, probably the most remembered decoy carver in Connecticut...He did all species of ducks, did them in different positions...Back in the 20's and 30's when he was carving heavy, he was considered a pioneer, he was different from everyone else. He kept them traditional and functional, but artistically eye appealing...he would never sell them, he would give them away...There's many years between us but I'm trying to pick up where he left off, just by researching his work and looking at all his carvings and talking to people who knew him. I like to continue the line, so that's where I fit in."

The first step is to decide what species of duck to carve, and whether it should be Maine, Massachusetts or Connecticut style. Keith then selects his wood, usually white pine, white cedar or occasionally bass, depending on the look of the grain. He makes a sketch of the form, cutting it out from a wood block using a band saw. He refines the shape by hand carving, then sands it down and paints it. Keith also creates bird carvings in realistic contemporary styles, based on detailed observation; he has carved a line of tropical birds after a trip to With his long years of experience in both traditional and contemporary carving, Keith is sought after as a teacher and a judge for competitions.

"The way the carving trend is, it's going towards the more realistic type and away from the folk art type of decoy that's the tool of the trade, so to speak...Back then it was just something that was patterned for the area, the conditions of the water, the area that you hunted...it was a functional thing that worked."

"We're a small family, close knit, all Connecticut people as far back as I can remember, all Yankees...I remember just once or twice as a kid going fishing with an uncle down at the shore, and I think that just did it...How do you say why you love the ocean? It's something inside...Something about sitting on the coast, watching the waves crash on the rocks, the solitude of it, studying the sea birds up there, it's just wonderful. It's just a feeling inside that I need to be there at least once or twice a week, so I take my dog down to the shore...I have to be on the water and there's got to be the ocean."

"I'm using the same basic techniques, same types of wood, same basic patterns, same styles for the area...I keep some of the mood or tradition inside me, so I'm portraying that with every decoy I do...Each decoy I carve probably has two hundred years of history behind it..."

"The way things are going, some species of duck like the greater scaup - they used to come into Connecticut 150,000 strong, but now they're down to almost endangered. It's the effect of the chemicals in the water making them sterile. Also the food they eat was a form of surf clam in Long Island Sound, but it's disappearing. Alternate types of food like the zebra mussel require more metabolism to digest properly, so they're not making it through the winter...This state used to be a number one wintering spot, now you hardly see them because there's nothing for them here."

The way I see it, there are three types of decoys that most decoy carvers make for themselves and their hunting rigs: the classic style of decoy, the modern style of decoy, and the carvers in the middle who like both. It has been my experience dealing with hundreds of decoy carvers, that most prefer the modern/contemporary style of decoy.....the ones that imitate the look and presence of the real bird. And to add to that.....these carvers prefer to paint their decoys with acrylics.

Me, if I had to pick one style to make....it would be hands down the classic decoy styles of New England makers such as Wheeler, Wilson, Crowell and so many others! I much prefer the "artistic" and "sculpted" style of decoy based on the original makers interpretation and artistic skills to create these masterpiece works of art!! And of course....painting the decoys I make with the same touch used by the masters’ hands with oil paints! I like so many others also enjoy making the modern realistic decoys.....but I design, carve and paint them with the same techniques from the masters hands!! For me, it keeps their memory and their decoy carving heritage and tradition alive! (2022)”

Additional materials exist in The CCHAP archive for these artists and this project.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.

Status

Not on view