"Auspicious Signs:: Jampa Tsondue, Tsering Yangzom, and Ngawang Choedar

SubjectPortrait of

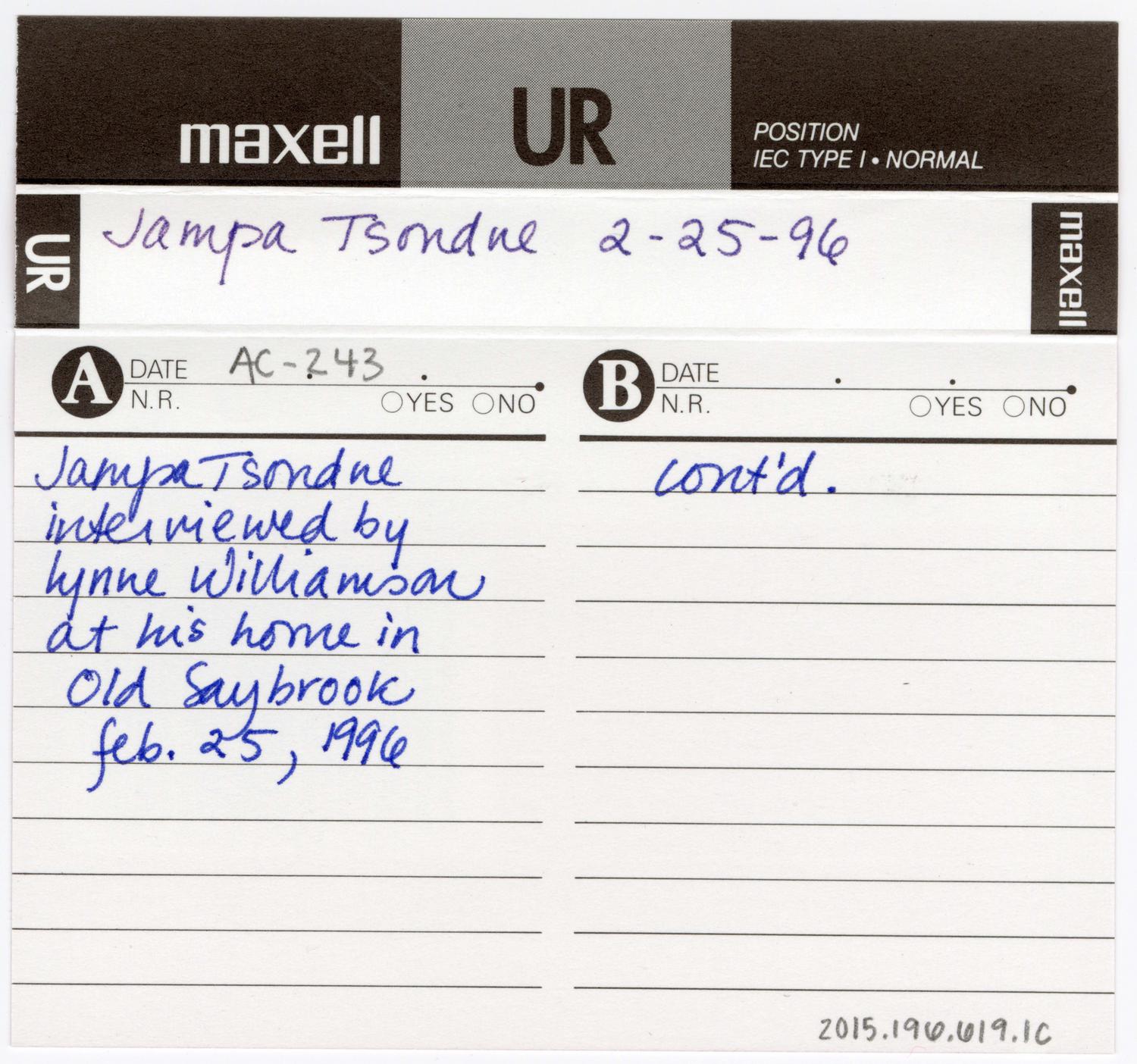

Jampa Tsondue

(Tibetan, born 1959)

SubjectPortrait of

Tsering Yangzom

(Tibetan)

SubjectPortrait of

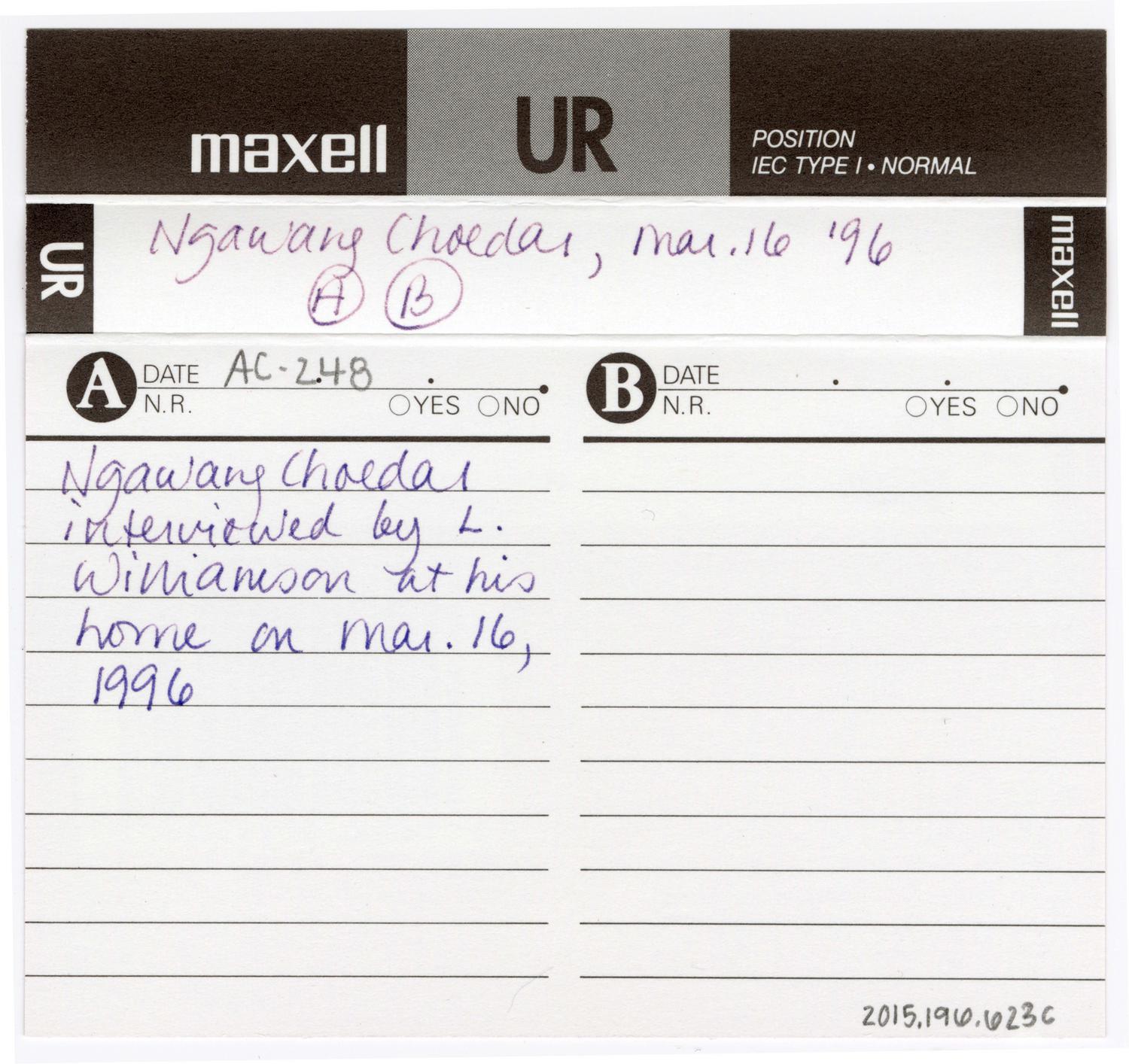

Ngawang Choedar

(Tibetan)

FilmmakerMade by

Winifred Lambrecht

(American)

Date1996-1998

Mediumreformatted digital file from VHS tape

DimensionsDuration: 9 Minutes, 26 Seconds

ClassificationsGraphics

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

CopyrightIn Copyright

Object number2015.196.607a-b

DescriptionVHS tape featuring three Tibetan artists: Jampa Tsondue (thangka painter), Tsering Yangzom (weaver), and Ngawang Choedar (woodcarver) showcasing their skills. The narrator explains their biographical history. Video created as part of the 1996-1997 exhibition project, "Auspicious Signs: Tibetan Arts in New England."

NotesVideo Credits: Producer: Institute for Community Reseach, Connecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program, Lynne Williamson.; Director: Winifred Lambrecht.; Camera and Technical Production: Winifred Lambrecht, Greg Watt.; Music: Lakedhen Shingsur, Connecticut Public Radio.; Funding: The National Endowment for the Arts Folk and Traditional Arts Program; the Connecticut Humanities Council; the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Community Folklife Program administered by the Fund for Folk Culture and underwritten by the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Fund; the Connecticut Commission on the Arts; and the Institute for Community Research. Weaving Consultant: Linda Hendrickson, Portland, Oregon.Subject Note: "Auspicious Signs: Tibetan Arts In New England" was an exhibit project developed by the Connecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program (CCHAP) at the Institute for Community Research in Hartford in 1996. The exhibit opening and a festival of Tibetan arts and music served as the major public events of an eighteen-month research and programming project conducted by CCHAP in partnership with the Tibetans. The project celebrated the Tibetan community's preservation and practice of their traditions in America.

Since the Tibetan Resettlement Project brought twenty-one Tibetans to live in Connecticut, the state has become home to one of the fastest growing Tibetan communities in the United States. Several Connecticut Tibetans are traditional artists of great skill who are deeply committed to expressing and passing on Tibetan culture. Members of the Tibetan community are also dedicated to educating others about the difficult history and circumstances of the Chinese occupation of Tibet.

The collaborative project team consisted of three Tibetan project assistants, exhibit designer Sarah Buie, the Tibetan Cultural Center of Connecticut, artist Sonam Lama who was at the time Vice President of the Massachusetts Tibetan Association, and curator/folklorist Lynne Williamson, then director of CCHAP. The interdisciplinary nature of the team served to broaden the project's outreach to regional Tibetan communities as well as to incorporate a rich variety of expertise and perspectives.

The project team produced an exhibit displaying Tibetan religious art as well as everyday traditional arts, a day-long festival featuring artists, performers, demonstrations, and discussions, and an illustrated catalogue. Artists Jampa Tsondue, Ngawang Choedar, and Tsering Yangzom were featured in a video documenting their artistic process.

Funders included the Lila Wallace Readers Digest Community Folklife Program administered by the Fund for Folk Culture and underwritten by the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Fund; the National Endowment for the Arts Folk and Traditional Arts Program, the Connecticut Commission on the Arts, the Connecticut Humanities Council and the Institute for Community Research.

To mark the exhibit opening, the Tibetan community held a festival attended by over three hundred people, including Tibetans from all over the region. Four music and dance groups performed outside, while in the exhibit gallery three Tibetan artists demonstrated weaving, woodcarving, and thangka painting. The event also featured a bazaar, a common Tibetan cultural activity. Many Tibetans are keen traders, maintaining links to Dharamsala, India, and Nepal through import of goods to the U.S. and sale through small shops here. Six Tibetan vendors from all over the region set up tables during the festival with a great variety of Tibetan books and crafts. Lakedhen and five other community members had risen at dawn to prepare food, which they sold during the day. Several speakers described the background of the project, the story of the Connecticut community, the current political situation in Tibet, and the history and character of Tibetan culture. Cholsum dance group from New York City and musicians Lakedhen and Thupten performed and accompanied the dancers. Singer DaDon and her group played for over an hour.

Biographical Note: Twenty-seven years old at the time of the Auspicious Signs project, Ngawang Choedar showed a remarkable skill in woodcarving. His father was a well-known Tibetan woodcarver and traditional architect from near Lhasa, who fled Tibet for Dharmasala, India. Ngawang inherited his father's love for wood, further developing his carving knowledge at the Tibetan Library in Dharmsala where he apprenticed for four years. Ngawang's teacher there was a monk from Kham in Tibet who both taught students and supervised them in making elaborate carved tables commissioned by monasteries in India and Japan. They also carved a wooden altar for the Dalai Lama. It could take as long as a year to finish a large table with several decorated panels carved with traditional Tibetan designs such as Buddhist symbols, mythological animals, and landscape scenes.

Ngawang brought his woodworking tools with him to Connecticut in 1992. He found a job in West Haven making specialized countertops, learning new techniques of industrial woodworking. The more delicate art of traditional Tibetan carving, as he learned it, is difficult to do in a small apartment even though Ngawang uses only his saw, whetstone, chisels, and the flat arm of a chair to create intricate, almost molded three-dimensional carved forms. Usually he carves pieces out of a soft pine called chil, easier to work than the hardwoods for furniture which require hammer and chisel.

After tracing designs (he uses many from his father) onto a flat piece of wood, Ngawang holds the wood with one hand while cutting shapes with his bamboo fret saw. This seemingly simple tool is ingenious and flexible, as it allows him to cut curved lines into tightly spaced shapes. By unstringing the serrated wire, threading it through a pierced hole in the center of the wood, then rewiring the saw, Ngawang can shape the middle of the wood block without cutting into it from the edge. Once the shapes are cut, depth and detail are added with a variety of gouges and chisels. To make a piece such as a large frame or table, individual panels or sections are carved, then assembled.

"The place I was born is near Mt. Everest. You can't see a lot of trees, you can't see lights, you can't see cars, you can't see anything! It's six or seven days walking through Nepal to the place I was born...my father built a monastery in that place. My dad and my teacher, they're the only ones who can draw the designs freehand and just carve it...that's why we need to keep all those designs they carved - write them down (copy them)...they learned all those designs in their lives and they are great."

Biographical Note: Tsering Yangzom weaves belts with traditional designs on her backstrap loom as well as wool material for blankets, aprons, jackets, and bags on a larger loom. Her skill, learned from her mother in a remote village on the Nepal/Tibet border, is one traditionally shared by rural women. When she was seven years old Tsering Yangzom's family fled Tibet, settling in a remote Nepali village near the Tibetan border. It was difficult for Tibetan exiles to make a new life there as they were foreigners, bringing few possessions and little money with them. One way for families to generate both income and necessary household furnishings was to utilize women's traditional weaving skills. Tseyang's mother made blankets, bags, warm coats - chupa, and married women's traditional striped aprons - pang-dhen out of cloth she wove from dyed sheeps' wool, as well as small carpets and seat coverings. These were also sold in shops in the town.

Tseyang and her younger sister were taught to card and spin yarn from sheeps' wool, and weave it into cloth, a common practice for Tibetan women. In school all children learned to make the patterned belts that Tibetans tie around their chupa. Later Tseyang worked in a factory handweaving Tibetan carpets as this industry grew in Nepal.

Tseyang brought to her new home in Old Saybrook the traditional narrow loom she used to weave belts, although she could not bring with her the larger loom for cloth. Belts are made on a thak-ti, a tension loom which uses a process called tablet weaving to create quite complex designs on belts up to six inches wide. Pierced thin leather cards, or tablets, are strung side by side onto individual vertical warp threads. Tension on the warp threads is provided as the weaver pulls against the threads attached to a backstrap tied around her waist. As she pulls, she rotates all the tablets at once, an action which moves some warp threads up and some down to create a space between them, in the manner of a heddle. She passes a thread horizontally through this space in a weaving motion, pushes it down tightly with a wooden beater, then rotates the tablets again to lift another set of warp threads before weaving again. The pattern is determined by the number of tablets strung onto certain colors of warp threads. In another photograph of this loom Tseyang has seven tablets strung with dark threads on either side, with twenty-four white thread cards between them, to make a simple two-color belt. Tseyang moved to Torrington, Connecticut then New York City to live.

"When we took refuge from Tibet and had no farms to grow things, to make a living, to survive we had to do this kind of thing...there was nothing we could do but making and selling cloth, blankets, bags, belts...the first thing is to keep the traditions of our culture. Second thing is when we lost our country Tibet, when the Chinese took over, there's no way to do other business. To survive we did this...the same things in Nepal as Tibet."

Biographical Note: Jampa Tsondue was born in 1959 just after his parents arrived in India, having left their farmland in Shigatse near Lhasa. Settling in Darjeeling, the family was visited by a monk-painter who noticed Jampa's talent. After school each day from the age of thirteen Jampa took art lessons from this teacher, Ngawang Norbu. Later Jampa moved south to Mysore to become an apprentice to this famous painter at the Gyudmed Tantric University, studying techniques of thangka painting for five years. The bond between master teacher and student can become very strong, almost familial. Jampa worked with his teacher, who also lived with the family, for the next fifteen years. Together they accepted commissions for thangka paintings, murals, and restoration of old art works. Their most important project took four painters nearly four years to complete - recreating forty-one thangkas in the Dalai Lama's collection, each 4 feet by 3 feet, depicting the past lives of the Buddha.

In 1992, Jampa was chosen by lottery to come to America with 1,000 Tibetans, and he settled in Old Saybrook where he still lives. Although working and raising three children, Jampa has completed several thangkas in America although each requires a long process; he does not make them for sale. Every Tibetan has a home altar, and Jampa has created an altar in his house where his thangkas are used by his family for meditation. He has been very active in the Tibetan Association of Connecticut, a social organization that serves the nearly 500 Tibetans that have settled in Connecticut (growing from the 21 who came in 1992). Jampa participates in community gatherings to celebrate Losar, New Year, and the Dalai Lama’s birthday. In February 2007, Jampa’s paintings and drawings were on display at Wesleyan University, at the Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies, organized by Patrick Dowdey, curator and professor at the Freeman Center. Jampa also did a demonstration of thangka painting there. This was his first exhibition in many years, and his first solo exhibit. Exhibitions and demonstrations featuring Jampa’s work have taken place at Trinity College, Hartford, the "Ambassadors of Folk: Connecticut Master Traditional Artists" exhibit at the Institute for Community Research in Hartford, the "Auspicious Signs: Tibetan Arts in New England" exhibition also at ICR, and an exhibit at the Connecticut Office of the Arts Gallery that celebrated 25 years of the Connecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program. Jampa has taught his daughter Yangzom to create thangkas. In 2015, Jampa received a Folk Arts Fellowship from the Connecticut Office of the Arts.

Biographical Note: Born in Gangtok, Sikkim in 1962, Lakedhen Shingsur is a natural musician who taught himself to play flute while at the Indo-Tibet Buddhist Cultural Institute school in West Bengal. He became a versatile musician also able to accompany on damyen. He formed an amateur dance and drama club which still exists to present Tibetan song and dance, learning songs from Tibetan elders living in Sikkim. For ten years he was a member of the Sikkim National Performing Arts Troupe, touring in India, Canada, the Middle East, and visiting the U.S. for the Festival of India in 1982. He has lived in Old Saybrook and Clinton, Connecticut since arriving in 1992.

Lakedhen's primary instrument is the transverse flute. Usually made of bamboo with six finger holes, these are played throughout the Himalayan region. As a working musician Lakedhen's repertoire included modern Indian film scores as well as the folk music of Tibet, Sikkim, and Nepal. He learned many songs from the director and other members of the song and drama troupe, representing a number of ethnic groups from the region. Love songs, traditional welcomes for guests, Buddhist spiritual lessons, historical events, dance songs, and odes to the beauty of Sikkim are some common folk song subjects.

Lakedhen has led a folk music and dance group from the Tibetan community in southeastern Connecticut, teaching students and performing at many community events. He was featured in the CD "Sounds Like Home - Connecticut Traditional Musicians".

"One of our songs is Dhana-Hain Roupaun: Sikkim the valley of rice, its smiling faces, its peace, prosperity and contentment, its imposing grandeur are all a part of its heritage. Another song is called Gha-To-Ki-To: An age old tradition of welcome. Guests are served chang, a millet brew, or soicha, butter tea, as a welcome in all Sikkimese homes."

Subject Note: In 1996, weaver Linda Hendricksen visited Torrington to meet Tsering Yangzom and discuss her method of tablet weaving. Linda was a paid consultant providing accurate descriptions of Tsering Yangzom’s weaving that would be used in the video of three Connecticut Tibetan artists produced by CCHAP/Lynne Williamson in 1998 (videography by Winifred Lambrecht). This video is in the CCHAP archive.

Biographical Note: Linda Hendricksen is a weaver specializing in tablet weaving, based in Portland, Oregon. “I've been weaving since 1984, and teaching since 1992. I teach and write about tablet weaving and ply-splitting; make instructional videos; and offer private instruction in my home studio in Portland, Oregon. I also have a web-based business offering books, tools, and kits for these techniques. My latest book is "How to Make Ply-Split Braids and Bands". One of my projects for 2015 is to make a digital version of "Double-Faced Tablet Weaving: 50 Designs from Around the World (self-published in 1996).

Additional audio, video, and/or photographic materials exist in the archive relating to these artists.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.

Status

Not on viewJampa Tsondue

2018 March 10