Hmong Wedding, Lao New Year, and Pysanky

SubjectPortrait of

Sai Xiong

(Hmong)

SubjectPortrait of

Boua Tong Xiong

(Hmong)

SubjectPortrait of

Dennis Kowaleski

(Ukrainian-American)

Date2000

Mediumborn digital photography

ClassificationsGraphics

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

CopyrightIn Copyright

Object number2015.196.433.1-.27

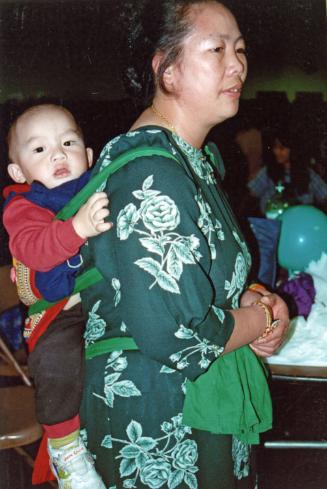

Description2015.196.433.1-.2: Images of young women wearing Hmong traditional dress. The woman on the left, Sai Xiong, married Boua Tong Xiong's son at this gathering. The unidentified woman on the right was the bridesmaid.

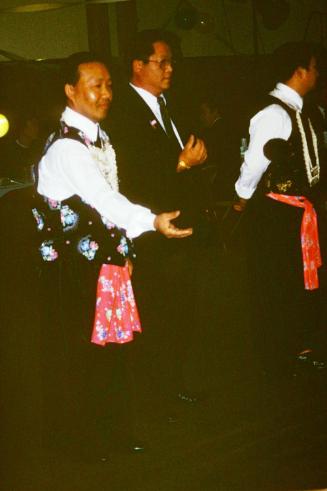

2015.196.433.3: Image of the bridesmaid at the wedding. Boua Tong Xiong on the right officiated the wedding.

2015.196.433.4: Image of members of the Xiong family with traditional foods at the Hmong wedding dinner.

2015.196.433.5: Image of a Ukrainian embroidery made by Dennis Kowaleski.

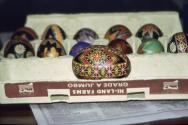

2015.196.433.6-.12: Images of Ukrainian pysanky made by Dennis Kowaleski.

2015.196.433.13-.14: Images of a Ukrainian embroidery made by Dennis Kowaleski.

2015.196.433.15-.19: Images of Ukrainian pysanky made by Dennis Kowaleski.

2015.196.433.20: Image of the pah khuane and flower decorations at the 2000 Lao New Year celebration.

2015.196.433.21: Image of dancers from the Lao Narthasin dance group sitting at a table with flower decorations at the 2000 Lao New Year celebration.

2015.196.433.22-.26: Images of members of the Xiong family with traditional foods at the Hmong wedding dinner.

2015.196.433.27: Image of young women wearing Hmong traditional dress. The woman on the left, Sai Xiong, married Boua Tong Xiong's son at this gathering. The unidentified woman on the right was the bridesmaid.They wear the traditional, old-style Hmong embroidered skirts probably made by their relatives in the home, Yee Xiong and Vang Xiong.

NotesSubject Note: The Hmong community in Connecticut, around 300 in number, is based mostly in the Enfield and Manchester areas. They work in factories and service occupations, as well as skilled manufacturing, often in aerospace industries. The Hmong came to the United States as refugees from the Indochina wars in the 1970s after the Communist takeover of Laos, sponsored by the American government because many Hmong assisted the military and the CIA. At that time the Hmong were persecuted in Laos, and this still continues today with considerable fighting going on. The Hmong are a tribal group originally from Mongolia who migrated to Laos where many still live today. There are also Hmong communities in northern Burma, Vietnam, Thailand, and China (where they are called Miao). 2015.196.433.3: Image of the bridesmaid at the wedding. Boua Tong Xiong on the right officiated the wedding.

2015.196.433.4: Image of members of the Xiong family with traditional foods at the Hmong wedding dinner.

2015.196.433.5: Image of a Ukrainian embroidery made by Dennis Kowaleski.

2015.196.433.6-.12: Images of Ukrainian pysanky made by Dennis Kowaleski.

2015.196.433.13-.14: Images of a Ukrainian embroidery made by Dennis Kowaleski.

2015.196.433.15-.19: Images of Ukrainian pysanky made by Dennis Kowaleski.

2015.196.433.20: Image of the pah khuane and flower decorations at the 2000 Lao New Year celebration.

2015.196.433.21: Image of dancers from the Lao Narthasin dance group sitting at a table with flower decorations at the 2000 Lao New Year celebration.

2015.196.433.22-.26: Images of members of the Xiong family with traditional foods at the Hmong wedding dinner.

2015.196.433.27: Image of young women wearing Hmong traditional dress. The woman on the left, Sai Xiong, married Boua Tong Xiong's son at this gathering. The unidentified woman on the right was the bridesmaid.They wear the traditional, old-style Hmong embroidered skirts probably made by their relatives in the home, Yee Xiong and Vang Xiong.

Connecticut Hmong people are both traditional and contemporary. Older women used to make the gorgeous applique and embroidery work known as paj ndau, and they still create traditional costumes for women and men, albeit with modern shortcuts (traditional dyeing techniques are replaced by printed cloth, for instance). Men who are traditional community leaders, such as Boua Tong Xiong, still perform wedding and funeral rituals, as well as conflict resolution according to time-honored practices. Hmong traditions practiced in Connecticut include embroidery and story cloths, funeral and wedding songs, music on the bamboo instrument qeej, ballads and courtship songs kwv ntxhiaj, and social dancing. Hmong leaders started the Hmong Foundation of Connecticut as a way to keep the community together and continue to provide many kinds of needed assistance. The Foundation, which is led by a Board of Directors, is open to all Hmong living in the state. Members provide services such as translation, transportation, family relocation to Connecticut, assistance with finding jobs and access to health care, Hmong language classes, and traditional Hmong advising and dispute resolution. The Hmong Foundation of Connecticut became a separate organization in 1996 after the Connecticut Federation of Refugee Assistance Agencies, an umbrella service group, disbanded. The group sponsors Hmong New Year in November and a celebration for Hmong high school graduates in June.

The Hmong have a number of sub-cultural groups; one of the distinguishing characteristics of the Blue Hmong is their custom of batiking cloth with blue indigo. One specific kind of textile that the Hmong have become known for are the “story cloths”. These are a comparatively new genre first made in the Thai refugee camps around 1975. In these embroidered pieces, direct figurative references are made to folk tales, myths, personal family stories, and scenes of village life. These story cloths also depict the turbulence and hardships of the war years in Southeast Asia. Hmong textile works also include many references to the natural world, to the plants and animals, which are native to the hills of Laos. (Winifred Lambrecht, Ph.D (CCHAP project partner); July 2006)

Biographical Note: Boua Tong Xiong (Blue Hmong) came to Connecticut in 1979, after fleeing from northern Laos with his family to Thailand, as so many Hmong had to do after the Communist takeover of Laos. Tong played an important role during the Vietnam War by assisting the U.S. government as part of the Special Guerilla Forces fighting in Laos. Because they were farmers in Laos, many Hmong chose to live in Enfield, a small town north of Hartford rather than settling in a larger urban area. The Hmong community consider Tong to be an important culture bearer, and many of his extended family members followed to live near him in Connecticut. Hmong communities throughout New England ask Boua Tong Xiong to preside over funerals and weddings, because of his experience, his beautiful voice, and his knowledge of the ritual songs, a necessary skill within this very traditional community. He also serves as a counselor to the community, helping to resolve disputes and lead diplomatic outreach to other Hmong families and communities especially in Fitchburg, Massachusetts and Providence, Rhode Island. Because the men who understand the complete rituals (which take days) are so few, Boua Tong is committed to passing on his knowledge, teaching young men to play the ritual bamboo instrument qeej and sing the wedding and funeral songs. He has participated in CCHAP’s Southern New England Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program for several years. In the early 2000s, he held regular weekend classes attended by between twelve and sixteen young men, either in his house (wedding songs) or in a nearby park - because the funeral rituals are traditionally performed outside. He also knows the joking and courtship songs sung by men and women. Tong regularly visits relatives in larger Hmong communities in California and Minnesota to refresh his knowledge of the rituals and songs. He worked with other veterans including Maj. Sar Phouthasack to establish a memorial in Middletown dedicated to Special Guerilla Unit veterans (including several Connecticut Hmong) who fought for and supported the United States in the Vietnam War. As a result of their efforts to pass the Hmong Veterans Service Recognition Act in Congress in 2018, Lao and Hmong veterans are now entitled to a military burial in Connecticut.

Biographical Note: Vang Xiong was a Hmong flute player and embroidery artist of great skill who lived in Tariffville, Connecticut with her family. She was the sister of Boua Tong Xiong. After 2000 she moved to California with some of her family. Contemporary Hmong decorative textiles (or “paj ndau”) include two major forms: applique and stitchery. The applique includes double applique and reverse applique; the stitchery is also of a variety of forms: cross-stitching and embroidery add texture and dimension to most pieces. One of her embroideries is in the CHS collection, collected by Lynne Williamson.

Biographical Note: Yee Xiong was a Hmong embroidery artist of great skill who lived in Tariffville, Connecticut with her family. She was the sister of Boua Tong Xiong. After 2000 she moved to California with some of her family. Contemporary Hmong decorative textiles (or “paj ndau”) include two major forms: applique and stitchery. The applique includes double applique and reverse applique; the stitchery is also of a variety of forms: cross-stitching and embroidery add texture and dimension to most pieces. Some of her embroideries are in the CHS collection, collected by Lynne Williamson.

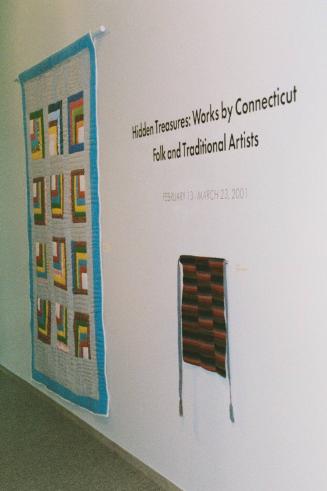

Biographical Note: Dennis Kowaleski is a Ukrainian-American artist who specializes in Ukrainian embroidery and pysanky, dyed Easter eggs inscribed with intricate Ukrainian designs. CCHAP visited him at his home in Thomaston, Connecticut to document his work as part of the Hidden Treasures exhibit project. The exhibition, "Hidden Treasures: Works by Connecticut Folk and Traditional Artists," held February-March 2001, was displayed in the Connecticut Commission on the Arts Gallery, 755 Main Street, Hartford. This location was on the ground floor of the Gold Building which housed Fleet Bank and United Technologies. The exhibit featured 27 folk and traditional artists whose fine work made by hand in Connecticut was rarely exhibited. The artists represented a wide range of ethnic and occupational communities located across the state. The Connecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program curated this exhibit to celebrate a decade of its work with folk and traditional artists in communities throughout Connecticut. Curator Lynne Williamson gave a gallery talk on Thursday, March 1, 2001, followed by a reception to honor the artists.

Subject Note for 2015.196.433.20-.21: Subject Note: Lao New Year is celebrated in Connecticut by members of the Lao community each April. Known as the Boon Pee Mai or the festival of the fifth month, this is a time of special meals and ceremonies lasting for several days. Traditionally, on the last day of the old year houses are cleaned and put in order as a symbolic activity intended to expel any bad spirits that may be hiding in the home. On the first day of the new year, people go to the temple where they wash the statues of the Buddha with perfumed holy water. The ceremonies ensure good health and prosperity in the new year. In Connecticut, Lao gather at temples for religious ceremonies, and hold special banquets that feature music and dance by local dance groups such as Lao Narthasin led by dance educator and chef Manola Sidara. Other events have included an annual presentation by the students of Lao Saturday School which ran for many years at Jefferson School in New Britain organized by Manola Sidara and Howard and Sue Phengsomphone. Many of these events are organized by the Lao Association of Connecticut. Many Lao New Year celebrations in Connecticut have involved guest artists from other cultural backgrounds and traditions. In 2008 and 2009, CHAP collaborated with WNPR’s acclaimed radio discussion show Where We Live to document several ethnic festivals across the state. Words and sound were woven together to create podcasts and audio slide shows that take viewers and listeners right to the festivals. This project visited and documented a festival at the Lao Temple in Morris.

Biographical Note: Lao Narthasin of Connecticut is a group of young Lao-Americans who study and perform traditional folk and classical dances from the southeast Asian country of Laos. Most of these dancers were born in the United States to parents who immigrated here from Laos. They study Lao language and culture in special classes offered by the organization Lao-American Culture of Connecticut in cities such as New Britain, East Hartford, and Bridgeport where many Lao are now living. The Lao Narthasin dance group developed out of the Lao community's desire to preserve its heritage in America. Members of the company, who reside in cities throughout Connecticut, are trained by experienced instructors from notable Lao dance families. The founder of the group, Manola Sidara, is a Lao dance educator and community activist whose life has been devoted to serving her community. Born in 1969 in Vientiane, Laos, Manola joined the National Dance School at the age of five, along with her sister. After her family fled Laos, she continued learning traditional dance with master dancer Sone Norasing in Colorado until moving to Connecticut in 1989. Lao Narthasin now includes a third generation of dancers, and instructors include former students such as dancer Nancy Sayarath. Dance traditions in Laos are either classical, performed at the royal palace, or based in the rural folk cultures of the over sixty ethnic groups in Laos. Lao Narthasin performs both dance genres. Dances include the Hoyn Phon Yhia Welcome Dance where fresh flowers are offered to guests, and the Pow Lao Dance, featuring dancers from different tribal groups. The graceful movements made by the dancers reflect qualities of beauty, respect, and politeness so valued in Laotian culture. Hand gestures also tell stories in the dances, with subtle movements symbolic of spiritual beings such as deities ascending in the heavens. Many of the dances celebrate community festivals - the rice harvest, water festival, New Year, or the Fireworks Festival bringing prosperity and good fortune. Lao Narthasin wears many different authentic costumes appropriate to each special dance. The group often performs at festivals and ceremonies at temples in Connecticut and Rhode Island.

Additional audio, video, and photographic materials exist in the archive relating to this community and its artists.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.

Status

Not on view