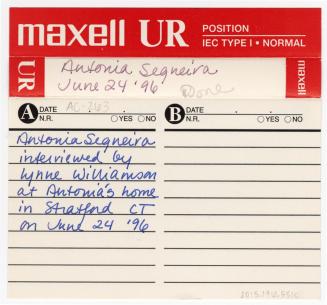

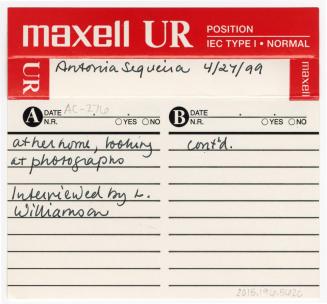

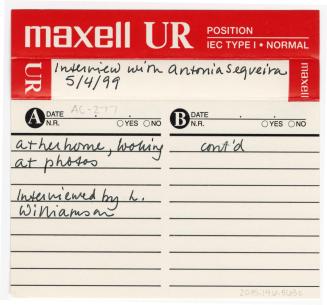

Cape Verdeans in Connecticut Community History Project Interview

SubjectPortrait of

Antonia Ignacio Ramalho Sequeira

Cape Verdean, 1924 - 2005

SubjectPortrait of

Mary Santos Sullivan

Cape Verdean, 1922 - 1999

SubjectPortrait of

Maria Teixeira

Cape Verdean

PhotographerPhotographed by

Phillip Fortune

Date1996-1999

Mediumphotographic print image

ClassificationsGraphics

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

Description2015.196.378.1: Image showing Antonia Sequeira (right) interviewing Mary Santos Sullivan while looking at family photographs, at Mary's home in July 1996. The interview was part of the Cape Verdeans in Connecticut Community History Project.

2015.196.378.2: Image showing a black and white portrait of Maria “Duducha” Teixeira, an experienced singer of morna and coladeira from West Haven. Her first stage performance was at age 12. She trained as a beautician, learned five languages, and had six children.

2015.196.378.3: Image showing a Cape Verdean pano, a woven cloth from the islands that was traditionally used in dancing. The pano is tied around a dancer's waist or folded and beaten as a drum, especially on the island of Santiago. This pano is in the CHS collection (2015.204.0), purchased for the Community History Project in 1999.

2015.196.378.2: Image showing a black and white portrait of Maria “Duducha” Teixeira, an experienced singer of morna and coladeira from West Haven. Her first stage performance was at age 12. She trained as a beautician, learned five languages, and had six children.

2015.196.378.3: Image showing a Cape Verdean pano, a woven cloth from the islands that was traditionally used in dancing. The pano is tied around a dancer's waist or folded and beaten as a drum, especially on the island of Santiago. This pano is in the CHS collection (2015.204.0), purchased for the Community History Project in 1999.

Object number2015.196.378.1-.3

CopyrightCopyright held by Duducha; Copyright held by Phillip Fortune

NotesSubject Note for Bridgeport Cape Verdean Community: Bridgeport is home to the largest settlement of Cape Verdeans in Connecticut. Drawn to this city by the labor needs of factories such as Bridgeport Brass, Carpenter Steel, Stanley Works, and shirt manufacturers, first men and then their families moved into the area of North Washington, Lexington, and Housatonic Avenue near the old brass works. Known as the Hollow, this section continues as a center where Cape Verdeans live, eat, shop, and attend St. Augustine's Cathedral and school on the corner of Washington and Pequonnock streets. Central High School, with fifty Cape Verdean students, has an active Cape Verdean club under the direction of educator Antoinette Soares Carpenter. Nineteen students in Bridgeport report Krioulo as their home language.Historically, immigrants to Bridgeport were from the island of Sao Nicolau, with a few from Fogo. Now newcomers come from several of the islands. Community leaders established the Cape Verdean Social Club in the early 1940s, taking over the site of Avelino Fernandes' restaurant at 200 North Washington Avenue. Men would gather there, as they do at all the clubs today, to socialize, share music informally, play the card game biska and the board game ouri. Events such as weddings, christenings, wakes, and religious celebrations of saints' feast days brought families to the club. Today the Associaçao de Clube Caboverdiana stands at the corner of Linen and Lexington streets, not far from the Vasco da Gama Portuguese Social Club where joint events are sometimes held.

Excluded from the men's associations, a group of young women from Bridgeport and Stratford, including Antonia Sequeira, formed their own organization in 1944. From the Portuguese Busy Bees they became the Cape Verdean Girls Social Club and then the Cape Verdean Women's Social Club. During the Second World War they sent gifts to men in the service and organized benefit dances and victory celebrations. Education has always been a revered goal of Cape Verdeans. The women's club continues a tradition begun by Bridgeport Cape Verdean Caesar Pina in 1957 of offering about ten scholarships each year to outstanding Cape Verdean high school students planning to attend college. Developed in 1993, the Cape Verdean Cultural Foundation devotes itself to presenting musical events and educational activities.

The Cape Verdean community used to hold a special Thanksgiving Day Mass every year at St. Augustine's Cathedral. Musicians such as violinist Julio Neves and others have played at the service. Priests would come from Roxbury, Massachusetts and sometimes Cape Verde to celebrate mass in both Portuguese and Krioulo. The choir sang religious songs and mornas and afterwards everyone would go to the Bridgeport Cape Verdean Club for breakfast. The parish demographics have changed in the 21st century, and mass is now offered in English, Spanish, and Vietnamese.

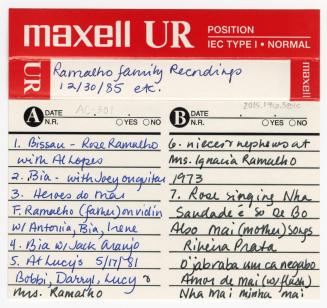

Biographical Note: Antonia Ignacia Ramalho Sequeira was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1924, the daughter of Ignacia (Soares) and Francisco “Chic Clau” Ramalho, immigrants from the Cape Verdean island of Sao Nicolau. Her parents lived first in Warren, Rhode Island, where they worked in the mills, moving to the heart of Bridgeport’s Cape Verdean community on Lexington Avenue shortly before Antonia was born. Antonia spoke only Krioulu until she went to school, after the family settled in Stratford in 1930. The Ramalhos were the first Cape Verdeans in Stratford’s Dewey Street area but others soon followed. Their neighbors Peter and Isabel Fernandes often hosted Cape Verdean sailors who would play music while Isabel sang and taught Antonia and her sisters “all the old songs.” Special family and community occasions such as christenings, as well as impromptu gatherings of friends, would lead to kitchen dances often lasting two or three days, with local families and traveling musicians joining in. Antonia loved the special community feeling of this music and dance, recalling, “People would come over early in the morning and they’d just play music. In the summer we would sweep the dirt and dance in our bare feet.” Antonia’s sister Rose, a talented singer, learned many Cape Verdean songs from her father who played the violin and toured with several bands. Pioneer music producer and distributor Al Lopes from New Bedford made one of the earliest Cape Verdean-American recordings, of Rose singing the morna “Bissau.”

Inspired by her traditional musical family and vibrant Cape Verdean neighborhood, Antonia developed a deep love and knowledge of her culture. She retained detailed memories of people and events, especially those related to music, and was able to record these memories on tape over the years. Always a collector and deeply involved in many organizations and activities, she kept detailed records of the community and its social events. Antonia’s collections of family and historical photographs comprise a rare documentary record of Cape Verdeans in Connecticut during the first half of the 20th century.

Among her numerous organizational affiliations, Antonia was a founding member of the Cape Verdean Women’s Social Club of Bridgeport (established 1944), and served as its president from 1965 to 1967 and again from 1970 to 2002. She spearheaded many projects designed to bring Cape Verdean heritage to public attention. In 1978, Antonia worked with Theresa Cardozo and others from the Women’s Social Club to sponsor a month-long series of lectures, exhibits, and concerts highlighting Cape Verdean culture at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut. She was a member of the Connecticut Friends of the Ernestina/Morrissey, a group responsible for bringing the schooner to Captains Cove in Fairfield in 1983, as a way to educate audiences about Cape Verdean immigration. Antonia, or “Tiny” as she was often called, held memberships and active roles in the Cape Verdean Women’s Scholarship Committee, the Cape Verdean United/Unidade Caboverdeana, the Cesar Pina Scholarship Committee, the St. James Choir, the Cape Verdean Cultural Foundation of Connecticut, and the Red Hat Society. Antonia coordinated regular cultural displays at the Bridgeport Public Library and the annual Thanksgiving Day Mass celebrated by Pio Groton of Boston at St. Augustine’s Church in Bridgeport. She was involved in providing donations to the Thomas Merton Soup Kitchen in Bridgeport and the celebration honoring Francisco Borges, the first Cape Verdean Treasurer for the State of Connecticut.

Alongside her love of Cape Verdeans and their culture, Antonia nurtured her family. She was married to Russell Sequeira and they lived in the same house where she grew up, raising their family of two sons and one daughter. Antonia also worked for many years at Burndy Corporation in Milford.

Antonia’s community showed its appreciation for her unwavering commitment by honoring her in several ways: she was selected as Woman of the Year in 1984 and had her name etched in the State Capitol Building in Hartford. The Cape Verdean Women’s Club held a special dinner dance in her honor in 2003 to mark her years of service to that group, and dedicated the Antonia Sequeira Library, an archive of her collected materials.

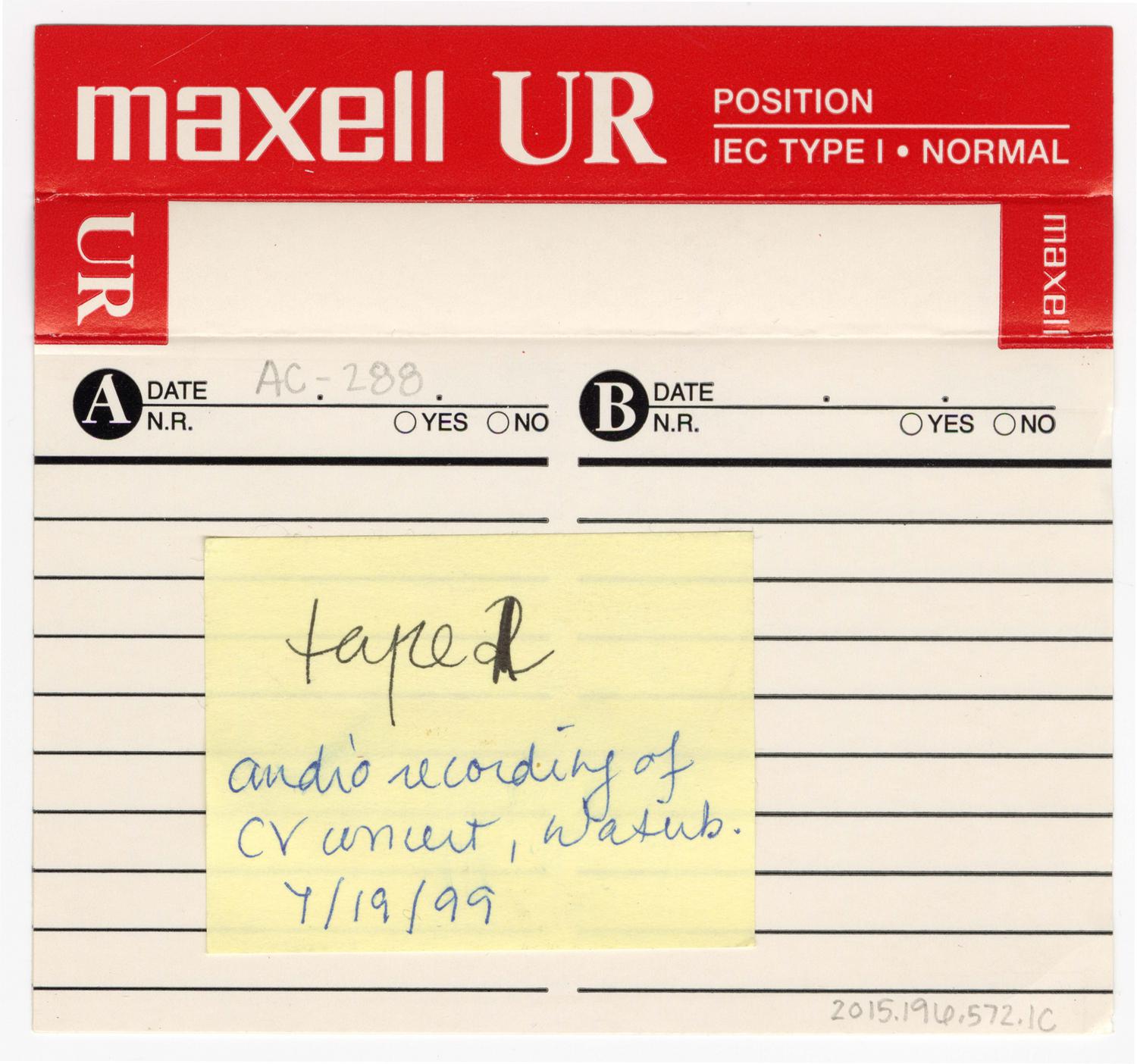

Antonia reached out to a wider public in the 1990s with her message of Cape Verdean pride. Representing the Cape Verdean Women’s Social Club, she participated in a new program for urban artists organized by the Connecticut Commission on the Arts and the Institute for Community Research. Her friend and colleague in that program, Joan Neves, was able to travel to Washington, DC in 1995 for the Smithsonian Folklife Festival which that year featured Cape Verdean culture. Inspired by that experience, Joan and Antonia began to plan for a long-term project to document their local community and its history. They found a partner in Lynne Williamson, then Director of the Connecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program, the statewide folk and traditional arts program at the Institute for Community Research. Together the team obtained grants from the Connecticut Humanities Council, the Connecticut Commission on the Arts, and the Lila Wallace Readers Digest Fund Community Folklife Program. For three years Antonia, Joan, and Lynne conducted taped interviews with Cape Verdean musicians and tradition bearers across the state, also documenting Cape Verdean neighborhoods, festivals, and activities. Their work resulted in a publication called "Connecticut Cape Verdeans: A Community History" that was distributed to every public library in the state and given to as many Cape Verdeans as possible in the region. The Waterbury Cape Verdean Social Club hosted a concert featuring musicians interviewed during the project, and a panel discussion was held at the Bridgeport Public Library. The materials collected by Antonia and the project team became a valuable archive of Cape Verdean life in Connecticut - information that had never been collected and made available to the public before. Copies are now housed at the Institute for Community Research in Hartford, and the Cape Verdean Women’s Club in Bridgeport.

Antonia’s work on the community history project continues to bear fruit. The book has been used by Cape Verdean organizations in Norwich and other Connecticut cities to educate people about the culture and especially the community’s gift of music. Younger Cape Verdeans in Waterbury, Norwich, and New Haven are coming forward to carry on the oral history work that Antonia believed in so fervently. Antonia passed away on February 28, 2005. She will be remembered as a tireless ambassadress for Cape Verdean culture; as a tradition bearer herself - someone who lived a life of deep Cape Verdean-American identity; and as a woman of grace and love. Her contributions will live on and nourish her people and our world forever. Antonia was posthumously inducted into the Cape Verdean Hall of Fame, in Swansea, Massachusetts.

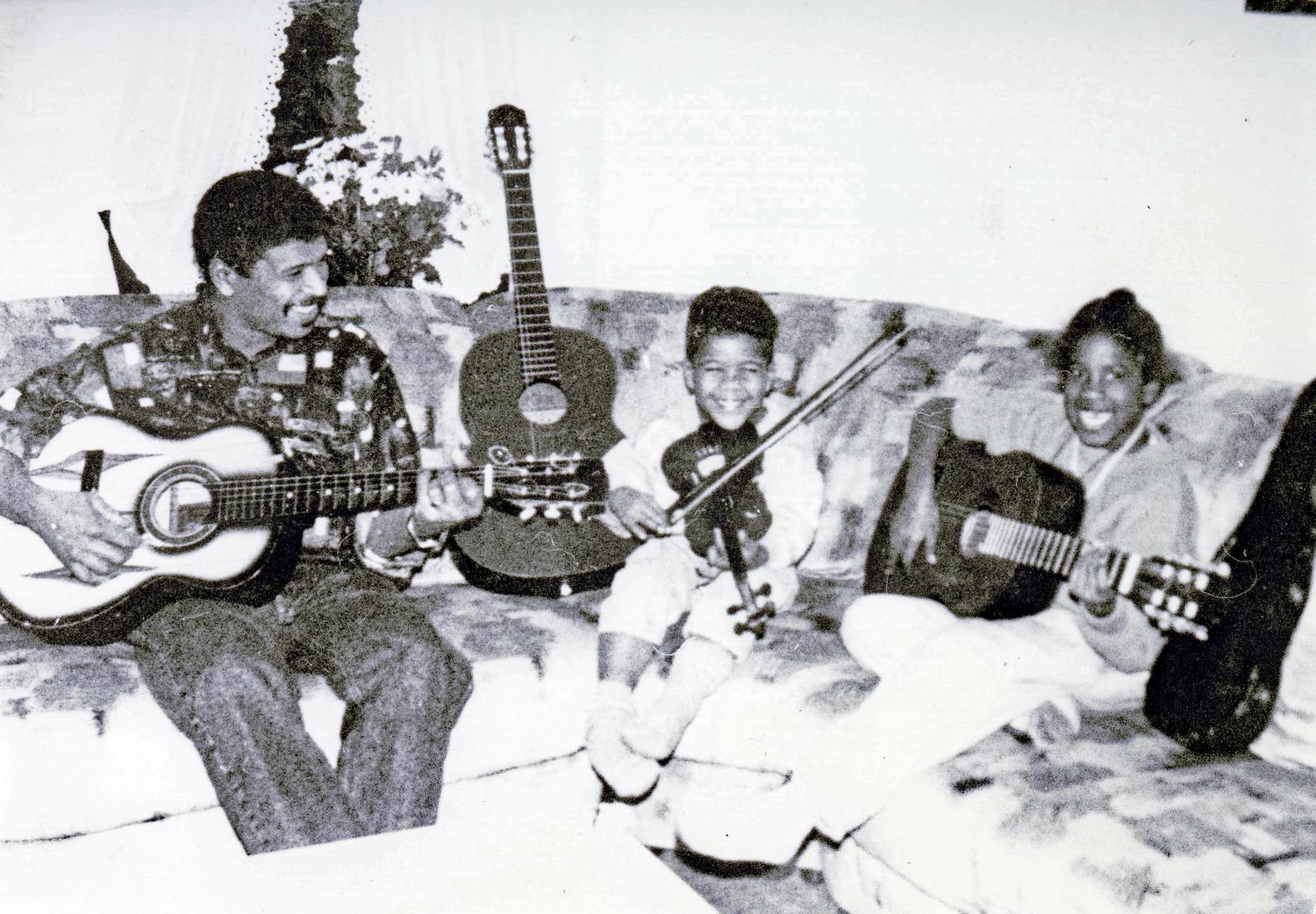

Biographical Note: Mary Santos Sullivan (1922-1999) was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts to Antonio Pedro and Claudia (Ribeiro) Santos who emigrated from São Nicolau and Maio, Cabo Verde respectively. Her father was a sailor and a musician. They moved to Connecticut when she was five years old. Her brother Dan played a lot of instruments and specialized in the mandolin, and her brother Peter played the viola.

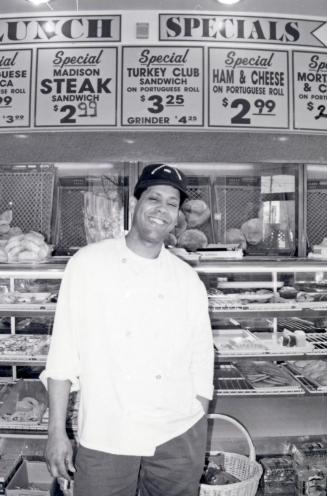

Biographical Note for 2015.196.378.2: An experienced singer of morna and coladeira, Duducha (Maria Teixeira), now of West Haven, Connecticut, grew up singing in Sao Vicente along with her father and her brother who played guitar. Her first stage performance at age 12 convinced Duducha that music would always be central to her life, but she has also trained as a beautician, learned five languages, and had six children. As others dedicated to traditional Cape Verdean music, she deplores the "globalization" of sounds and influences favored by some of the younger generation. Being in America has brought both new Cape Verdean experiences - she danced kola for the first time last New Year - and nostalgia: "Now I love my music more than when I was in Cape Verde. When I sing morna it goes straight to my heart - we feel it." People say of her performances "Her hands will give you the words."

Subject Note for 2015.196.378.3: This pano was collected from Cape Verde by project participant and videographer Joan Neves of Stratford for the Cape Verdean Community History Project. This pano is now in the Connecticut Historical Society collection (2015.204.0). In Cape Verde, panos are woven from cotton (usually in black and white) on narrow looms and stitched together in an open structure somewhat like kente cloth. Panos are often worn by women when dancing batuku (especially on the island of Santiago, which has the most African-influenced culture) - the cloth is folded and tied around the waist to emphasize the hip movements in the dances. Sometimes panos were folded up into thick "pillows" then placed on their laps by singers to serve as drums, especially during times when drums were forbidden by the Portuguese rulers of the Cape Verdean islands.

Subject Note: Connecticut has the third largest Cape Verdean population in the United States (after Rhode Island and Massachusetts), with active and growing communities in Bridgeport, Waterbury, and Norwich. Starting in 1996, the Connecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program of the Institute for Community Research (and now at the Connecticut Historical Society) participated in a statewide public history project with one of the state's most interesting but little-known ethnic groups. The Cape Verdean presence in New England dates to the 18th century, and new immigrants from Cape Verde continue to arrive. However, libraries, even in cities with a sizeable Cape Verdean presence, hold little information about the history and culture of this group generally, and virtually nothing about Connecticut's estimated 5,000 Cape Verdeans. Yet the cultural traditions of Cape Verdean-Americans remain strong, deeply felt, and regularly practiced. From their early presence as whalers on New England schooners to the burgeoning popularity of their distinctive music both globally and locally, Cape Verdeans have contributed much to the character, the labor force, and the culture of southern New England.

In 1996, CCHAP began a three-year project to document Cape Verdean musicians and tradition bearers across the state, especially in Waterbury, Bridgeport/Stratford, and Norwich. Together with community scholar Antonia Sequeira, CCHAP conducted analog tape interviews; videotaped performances; photographed festivals and community activities; and collected copies of rare books of songs, CDs and tapes, historical photographs, and research materials. In several cases the documentation preserves records or images of people and places that no longer exist. This work resulted in a publication called "Connecticut Cape Verdeans: A Community History" that was distributed to every public library in the state and given to as many Cape Verdeans as possible in the region. On July 17, 1999, the Waterbury Cape Verdean Social Club hosted a concert featuring musicians interviewed during the project, and a panel discussion was held at the Bridgeport Public Library. The materials collected by Antonia and the project team became a valuable archive of Cape Verdean life in Connecticut - information that had never been collected and made available to the public before.

CCHAP continues to expand the collection through ongoing work with this community, most recently assisting and documenting the historic preservation of St. Anthony’s Chapel and local stonemasons in Norwich. Cape Verdean musicians involved in the Southern New England Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program have also been recorded for the archive. These and other materials comprise a unique collection within the CCHAP archive. Very little available information exists in print on Connecticut Cape Verdeans, while community scholars actively collect family histories and host regular music events. Original interview recordings and copies of materials gathered are now part of the CCHAP archive at the Connecticut Historical Society. Some materials were also copied and donated to the Cape Verdean Women’s Club in Bridgeport.

Building on the earlier oral history work conducted by community scholar Antonia Sequeira, CCHAP collaborated with her and a number of Cape Verdeans to develop "Cape Verdeans in Connecticut: A Community History Project." In conversations with community members of all ages CCHAP heard time and time again of the importance of music to Cape Verdeans. More than entertainment, Cape Verdean music provides both a focus of ethnic uniqueness and a historical record of events, memories, and the movement of people. Music also serves to link Cape Verdeans in diaspora with loved ones back home and across the world. Music, situated at the heart of Cape Verdean cultural expression, became the project's entry point into an examination of tradition, growth, and change in the Connecticut community. The goal of the project was to collect video- and audio-taped interviews with musicians and other tradition bearers, along with their family photographs and other memorabilia, in order to gain an insight into the patterns of social change and cultural life in this community in Connecticut. The primary resource material gathered through the project is now archived at the Connecticut Historical Society.

The inspiration for this project began when Antonia Sequeira of the Cape Verdean Women’s Social Club of Bridgeport, along with her friend and colleague, videographer Joan Neves, participated in the Inner City Cultural Development Program organized by the Institute for Community Research and the Connecticut Commission on the Arts. A grant from that program enabled Joan to travel to Washington, DC in 1995 for the Smithsonian Folklife Festival which that year featured Cape Verdean culture. Inspired by that experience, Joan and Antonia began to plan for a long-term project to document local Cape Verdeans and the community’s history in Connecticut. They found a partner in Lynne Williamson, then Director of the Connecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program, the statewide folk and traditional arts program at the Institute for Community Research. Together the team obtained grants from the Connecticut Humanities Council, the Connecticut Commission on the Arts, and the Lila Wallace Readers Digest Fund Community Folklife Program. For three years Antonia, Joan, and Lynne conducted taped interviews with Cape Verdean musicians and tradition bearers across the state, also documenting Cape Verdean neighborhoods, festivals, and activities.

Antonia Sequeira and Lynne Williamson served as project co-directors. The full project team included Joan Neves as videographer, Koren Paul who transcribed the interview tapes, anthropologist Laura Pires-Hester, Pelagio Silva as concert organizer and emcee, and video producer Pedro Cardoso. Jo Blatti and Susan Hurley-Glowa contributed essays to the project book. Other Cape Verdean resource people included Jorge Job, John deBrito, Raquel Figueiredo, Elaine Santos Kain, José Conceiçao, Carlos da Graça, Johnny Andrade, Romeo Moore, Mary Anne Monteiro, Maria Lalache Spencer, Luca Cardozo, Marge Santos, Duducha, Mary Santos Sullivan, Claudia Silva, Anna Stanley, Anna Soares, Gertrude Duarte, Phyllis Williams, Roberta Delgado Vincent, Freddie Gonsalves, Philip Marceline, Antonio Sr., Abel, José and Matthew Santos, as well as Joao Cerilo Monteiro, Ray Almeida, and Ron Barboza.

The project was supported by the Lila Wallace Readers Digest Fund Community Folklife Program through the Fund for Folk Culture; the Connecticut Humanities Council; the Institute for Community Research; the National Endowment for the Arts; and the Connecticut Commission on the Arts.

Cape Verdean traditional culture inevitably changed with the mass migration of people from the islands to America. Transplanted practices have themselves evolved in the late 20th and early 21st centuries as the second and third generations are born and grow up in a vastly different society. Many in Cape Verdean communities in Connecticut adhere to traditions which although altered in some ways, maintain both the flavor and meaning of their origins. The constant influx of new Cape Verdeans from the islands freshens familiarity with older customs while bringing forward cultural expressions which before 1975 were forbidden under Portuguese colonial rule.

Many Connecticut Cape Verdeans and community organizations remain actively involved in sustaining heritage through regular educational and cultural activities. Wherever they settled, Cape Verdeans formed clubs and associations, a direct maintenance of the island tradition of tabanka. These mutual aid societies in Cape Verde provided essential assistance and services for local inhabitants suffering from constant drought, poverty, and colonial neglect. In America early immigrants from the town of Praia on the island of Santiago organized the Holy Name Society in Boston. Men from this group traveled all over New England, especially during the Depression, to distribute clothes, food, or services. Antonia Sequeira remembers them helping her father to dig and plant a garden behind the family's house in Stratford. In the late 1930s and 1940s, communities established Cape Verdean social clubs which still flourish, a direct continuation of the tabanka tradition. The concept of assistance for those in need continues in the regular Cape Verdean practice of sending oil drums packed with clothes and other American goods to families in the islands, especially during the frequent drought-related famines.

Separation from their homeland led many Cape Verdean immigrants to compose mornas, songs of great longing and sadness. Mornas remain beloved especially by the older generation who remember the reasons for composing them. Other traditional musical forms such as coladeira, mazurca, and samba are enjoying something of a revival among younger Cape Verdeans, while the African-influenced funana is wildly popular on the contemporary club scene. Playing instruments, singing, dancing, and drumming still happen spontaneously at festivals and social gatherings. Despite the cold of a Connecticut winter, some hardy musicians go door to door in Waterbury, Bridgeport, and Stratford, performing canta reis, the traditional New Year serenades. Cape Verdean wakes sometimes feature the choroguiza, a chant lamenting the deceased. The tradition of sending verbal messages via packet boats to families back in the island kept immigrants in touch across the ocean. The popular coladeira Rozinha is a mantenha, a message to Rozinha from her lover working abroad, asking her to wait a year until he can return to marry her. Connecticut musicians such as Jorge Job have been composers of mornas and other Cape Verdean song styles, while the Waterbury community maintain the repicar de tambor, a drumming and dance tradition practiced at the Festa de Sao Joao in June.

The project and the collected archive materials include many examples of locally composed and performed music, along with interviews with musicians and culture bearers and photographs, videos, and other recordings of them.

Additional materials exist in the CCHAP archive for this community and these activities.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.

On View

Not on view