Lebanese Mahrajan Festival and Mundillo Workshop, 1999

SubjectPortrait of

Nehme Atallah

(Lebanese)

SubjectPortrait of

Doña América Nieves

(Puerto Rican)

SubjectPortrait of

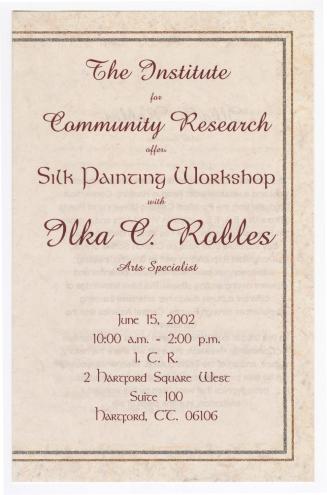

Ilka Robles

(Puerto Rican, born 1953)

DateAugust 1999

Mediumnegative film strips

ClassificationsGraphics

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

CopyrightIn Copyright

Object number2015.196.338.1-.25

Description2015.196.339.1-.9 are photographs of Nehme Atallah singing at the Lebanese Mahrajan Festival held in Wolcott, Connecticut on August 7 or 14, 1999.

2015.196.339.10-.25 are photographs of the Mano a Mano Project Mundillo Lace Making Workshop taught by América Nieves. The workshop was held at La Casa Elderly Housing, Park St., Hartford on August 9-13, 1999.

(.1-.9) Singer Nehme Atallah with musicians on stage at the Lebanese Mahrajan Festival.

(.10) América Nieves making lace.

(.11-.14) A piece of Doña América's lace displayed on the banner from Fomento - “Artesanía Puertorriqueña / Compañía de Turismo.”

(.15) América Nieves making lace.

(.16-.17) A piece of Doña América's lace displayed on the banner from Fomento - “Artesanía Puertorriqueña / Compañía de Turismo.”

(.18) Workshop participant Ilka Robles with Doña América Nieves, workshop leader/artist.

(.19) Doña América Nieves seated. She is wearing a lace collar she made.

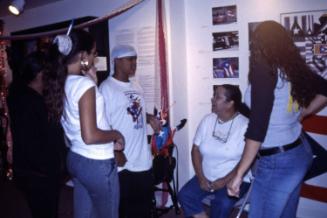

(.20) Workshop participant Ilka Robles and Kaleitha Wiley with Doña América Nieves, workshop leader/artist. They are holding mundillo looms on their laps.

(.21.-24) Workshop participants holding looms and awards. Pictured left to right are two unidentified participants (possibly Marie Hubbell and Carmen Castillo), Ilka Robles, Doña América, Kaleitha Wiley, and Sonia Castro.

(.25) Marie Hubbell wearing a lace scarf.

NotesBiographical Note for 2015.196.339.1-.9: Biographical Note: Nehme Atallah is a Lebanese singer based in Waterbury CT. He sings many kinds of Arabic music - traditional, popular and liturgical music. Nehme leads the choir and sings in the Mass every Sunday at Our Lady of Lebanon Church, Waterbury, as lead cantor. He can also sing Islamic music and has done so in mosques. Previously he was part of a band and he still sings solo at parties, weddings, celebrations. Nehme always performed at the opening of the Mahrajan held at the Ehden Lebanese Club annual festival, singing the Lebanese national Anthem and folk and liturgical songs important to that town in Lebanon.2015.196.339.10-.25 are photographs of the Mano a Mano Project Mundillo Lace Making Workshop taught by América Nieves. The workshop was held at La Casa Elderly Housing, Park St., Hartford on August 9-13, 1999.

(.1-.9) Singer Nehme Atallah with musicians on stage at the Lebanese Mahrajan Festival.

(.10) América Nieves making lace.

(.11-.14) A piece of Doña América's lace displayed on the banner from Fomento - “Artesanía Puertorriqueña / Compañía de Turismo.”

(.15) América Nieves making lace.

(.16-.17) A piece of Doña América's lace displayed on the banner from Fomento - “Artesanía Puertorriqueña / Compañía de Turismo.”

(.18) Workshop participant Ilka Robles with Doña América Nieves, workshop leader/artist.

(.19) Doña América Nieves seated. She is wearing a lace collar she made.

(.20) Workshop participant Ilka Robles and Kaleitha Wiley with Doña América Nieves, workshop leader/artist. They are holding mundillo looms on their laps.

(.21.-24) Workshop participants holding looms and awards. Pictured left to right are two unidentified participants (possibly Marie Hubbell and Carmen Castillo), Ilka Robles, Doña América, Kaleitha Wiley, and Sonia Castro.

(.25) Marie Hubbell wearing a lace scarf.

Nehme took music lessons when young in Lebanon at a music school so he is formally trained in the complicated Arabic keys. He joined Arabic music bands in Lebanon, and sang in church in Lebanon. 25 years ago he was taught by Prof. Nassir, in Connecticut in an apprenticeship; the teacher played the oud and Nehme would sing.

Church music and more popular or classical Arabic music have the same sounds but different texts. Nehme was an altar boy and sang in the choir; his father sang church music and the whole family sang in the choir both in Lebanon and in Connecticut. “My father asked me to start singing with him in church, and I did it, and since then I have worked with my children – 3 boys, and my nephews (and one niece) including this apprentice John, he’s the best. So this program will keep the family tradition going.” Nehme taught his nephew John Atallah liturgical and Lebanese folk singing under the Southern New England Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program Years 13 1nd 14 (2010-2012), and John became able to sing the liturgy for an entire church service on his own at that time.

“Back when I came to the US in 1986, no one was singing at Our Lady especially during communion. I started singing by myself, no one asked me! We improved the music in the church here, now I have someone playing on the organ to accompany me. Now our musical liturgy is so well known that we are shown on national TV, and I am asked to sing at the Maronite churches around western CT. An Aramaic scholar from Yale visited the church - he played the organ and I was singing, he praised my work even though he is an expert and I am not formally trained. My voice is in the music – I have experience, not formal. I enjoy to give my experience to someone else, to tell him how to be a singer, it is not enough to be a singer – you have to put the heart in it. The music goes from my heart to my brain, not the other way!”

(CCHAP interview 2010)

Nehme served as a mentor in Lebanese liturgical and folk music as part of the Southern new England Traditional Arts Apprenticeship program in Years 13 and 14 (2010-2012). In the first year he taught his nephew John Atallah elements and chants of Maronite liturgical music, and John was able to lead the singing for a mass. In the second year, Nehme’s student was Chris Skayem who learned both folk songs and church songs. Chris became part of the Choir at Our Lady of Lebanon. Nehme also has mentored Massia Atallah who immigrated from Lebanon to the Waterbury area. Topics taught by Nehme during the apprenticeships included: articulation and accent in Arabic, Assyrian, and Aramaic; also some hymns in English that were easier for the students who were born in the U.S.; fitting the words to the music; following the notes, the bayat (a complex set of rules for composing and performance) – they are difficult because highly ornamented; and learning the liturgical chants. Songs learned included the Lebanese National Anthem (based on a folk song) – kolonas lelwatan; Debke (social dance) songs – rajah yetaamar lebnan; bessahaha tlaina; taloo hbabna; ammer ya mealemleaamar; traditional songs – nassam aliana elhawa; alrosana aladaloona; behebak ya lebnan; and old chants – ataba; mijana; assayed. Nehme and students were assisted and accompanied by Choir musician Nadim Rjeili on the korg (organ), because this is done in performance and festivals.

Subject Note for 2015.196.339.1-.9: The Lebanese communities in Waterbury and Danbury are primarily Christian, celebrating the Maronite rite in the Antiochene-Syriac tradition within Catholicism. The liturgy is offered in a mixture of Arabic, Syriac, and English languages. There are three Maronite churches in Connecticut – Our Lady of Lebanon in Waterbury, St. Maron in Torrington, and St. Anthony in Danbury. The Waterbury Lebanese community traces its origins to the area around the town of Ehden in northern Lebanon. Several families from Ehden immigrated to Waterbury from Ehden in the early 1900s to work in local factories. In 1915, they formed a social club which also held church services; the club became registered with the state in 1948. Priests would travel from St. Maron Church in Torrington to hold Maronite liturgy services, then in 1975 the community established its own Maronite church in Waterbury. Our Lady of Lebanon moved to its present home on East Mountain Road in 1982. The Ehden Lebanese Club on the Waterbury-Wolcott border held an annual “Mahrajan” or summer festival annually in August from 1959 to 2018, and the Club also presented a winter “hafli” or party in February for many years to raise funds for its charity activities. These popular social gatherings included Lebanese traditional music, folk dancing, traditional foods, crafts displays and sales, and children’s activities. In 2000, the community added a new event, the Taste of Lebanon, on the grounds of Our Lady of Lebanon, also featuring music, food, a dance group, crafts and hookah sales, raffles, and more. CCHAP has worked with the community for many years, documenting the festivals, assisting the Club with planning for activities, and supporting two apprenticeships in Lebanese liturgical singing.

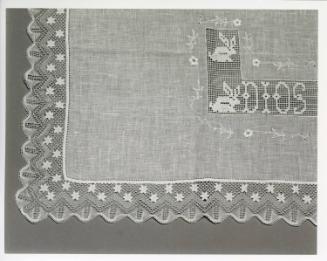

Biographical Note for 2015.196.339.10-.25: Born and raised in Moca, the center of Puerto Rico's unique mundillo tradition, Doña América is one of the area's best known lacemakers. She makes all kinds of lace - borders, bodices, collars, baby booties, handkerchiefs, etc. for neighbors and for customers who commission her work. Her styles and designs are numerous and range from simple openwork to detailed and elaborate leaves, flowers, or lattices. Mundillo is made on a "pillow" set into a wooden frame. The paper pattern is pinned to the pillow, the threads are wound onto bobbins which are manouvered and twisted around each other and the pins to form the lace. This technique and particular equipment is found only in Spain and Puerto Rico. Young girls who left school to work in the fields or the factories of northwest Puerto Rico gained income from doing needlework piecework at home for the American clothing companies in the area. Almost every family, including Dona America's, had women who knew mundillo, so it was easy to watch and learn. Doña América taught English in a local community college, and she has traveled to the U.S. often to demonstrate and give workshops. Her basic workshop curriculum was included in the supplementary materials.

“Doña América Nieves learned to make lace from her mother before she went into first grade. Lacemaking provided a valuable income source for the family during the six months of the year when her father, a sugar cane cutter, had no work. She has continued to make exquisite lace, even while earning a master's degree in education and working as an English teacher. She teaches lacemaking, participates in lace guilds, and demonstrates her art widely in Puerto Rico and the U.S.

Towns such as Moca, Aguadilla, and Isabela in northwest Puerto Rico are the home of a lace making tradition brought to the island by Spanish nuns. Traditional Puerto Rican lace is made on a small loom called mundillo, which has a rotating pillow-shaped drum. A paper pattern is held in place on the cushion with hundreds of pins marking the design. Thread carried on as many as fifty wooden bobbins (called bolillos) is woven around the pins to make the intricate designs take shape. The clicking of the wooden bobbins creates a delicate, musical rhythm.

A common source of income for rural women, lace making was also taught at school, through apprenticeships at workshops, and at needlework factories in the towns. During the second decade of the 20th century needlecrafts such as bobbin lace were in great demand due to their practical use, their timeless beauty, and the fashions of the day. They were used, and still are, in handkerchiefs, tapestry, linens, women's undergarments and clothing, baptismal and wedding gowns, and children's wear. Needlecraft continues to represent an important factor in Puerto Rico's economy.”

Subject Note for 2015.196.339.10-.25: A locally-based team of Puerto Rican artists, in collaboration with CCHAP at the Institute for Community Research, Guakia, and the Crafts Development Office of Puerto Rico's Economic Development Department (PRIDCO), worked together to bring a multi-faceted program of Puerto Rican traditional arts to Hartford during the summer of 1999. "Mano a Mano: Puerto Rican Traditional Arts from Island to City," began with the July 1, 1999, opening at the ICR gallery of an exhibition of fourteen craft forms practiced in Puerto Rico. Later in the summer, five master traditional artists traveled from Puerto Rico to offer week-long workshops in their craft forms to the public. After the workshops ended, participants who wanted to continue working with their crafts were mentored by the local artists on the project team.

This project was funded by the Lila Wallace Readers Digest Fund Community Folklife Program, the Roberts Foundation, the Greater Hartford Arts Council, the National Endowment for the Arts, the CT Commission on the Arts, PRIDCO, and the Institute for Community Research

Members of the project team were Melanio J. González, Pavlova Mezquida (PRIDCO), Glaisma Pérez-Silva, Graciela Quiñones-Rodríguez, Marcelina Sierra, Victor M. Sterling, and Lynne Williamson. Because of the knowledge and time needed to locate and purchase appropriate materials for the five workshops, ICR hired a local Puerto Rican artist, luthier Graciela Quinones-Rodriguez, to help coordinate this important aspect as well as recruitment of workshop participants.

The project furthered many goals important to the team, including promoting awareness of the contributions of Puerto Rican artists, increasing access within the Puerto Rican community to training in art and entrepreneurial skills, and encouraging relationships across generations. The traditional arts and crafts of Puerto Rico remain vibrant and beloved, both on the island and in the new places where Puerto Rican people have settled. The project celebrated the strong cultural traditions remembered and practiced by so many in Hartford's large Puerto Rican community. Artistic, social, and cultural practices within Connecticut Puerto Rican communities show a regular and active maintenance of familiar traditions which link urban Puerto Ricans to the island, to which many return for visits. The primary goal of the project was to reinforce these patterns of cultural practice and remembrance. Other goals included: 1. To address the need for more public programming and education in Puerto Rican cultural expressions, both for members of this community and for general audiences; 2. To reinvigorate local Puerto Rican artists by connecting them with master traditional artists from the island who rarely visit the mainland; 3. To help preserve knowledge and practice of Puerto Rican traditional art forms; 4. To provide training and support for local artists who wish to begin or continue to develop an economic base for their artistic productions.

The exhibition drew from the work of master artists and their apprentices who participated in PRIDCO's Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Project. Through the Crafts Development Office of the Puerto Rico Industrial Development Company (PRIDCO), Puerto Rico hosts an island-wide training program in traditional arts. Law 166, first passed in 1986, mandates that five government agencies in Puerto Rico provide services to artisans for their education and for the marketing and promotion of their work. This enlightened policy recognizes that traditional arts contain great cultural value because they express the collective wisdom and the soul of a community of people. Traditional arts also represent a vital link to the past, as they are transmitted from one generation to the next through long-term, informal, one-on-one teaching between a master artist and a student. Learning an artistic form through the process of apprenticeship is a powerful way to pass on cultural knowledge as well as the craft itself; this process also helps to develop relationships across generations.

On display from July 1-October 1999, the exhibit was designed and installed by the same team which produced ICR's successful Herencia Taína exhibit in 1997. PRIDCO loaned art works from its Traditional Arts Apprenticeship project, featuring 16 important craft traditions practiced in Puerto Rico today. Traditions featured included: Marímbolas/Percussion Instruments; Panderos/Plena Tambourines; Volantines/Kites; Vejigantes/Coconut Masks; Hatillo Mascaras/Wire Net Masks; Artesanía en Lata/Tin Crafts; Talla de Gallos/Carved Roosters; Alfarería Tradicional/Indigenous Pottery; Encuadernación/Bookbinding; Papel Maché/Papier Maché; Talla de Santos/Saint Carvings; Estampas Típicas/Folk Houses; Tejido de Bejuco/Liana Weaving; Tejido de Enea/Cattail Weaving; Mueble de Mundillo/Lace Cushion and Holder; Bolillos/Bobbins; Mundillo/Lace.

Based on fieldwork in the Hartford community, ICR and Guakia added examples from local artists working in similar traditions. Based on research done by the PRIDCO's crafts apprenticeship project, Lynne Williamson edited, with PRIDCO and Hartford members of the project team, extensive bilingual labels explaining the art forms. The signage was produced by the Peabody Museum in New Haven. At the opening, which was a Greater Hartford Arts Council First Thursday event, the local cuatro group Amor y Cultura performed.

Puerto-Rican based artists giving workshops were: Angel del Valle - pandero making and playing; Amelia Fonseca - the art of cake decoration; Vicente Valentín - cuatro building; América Nieves - mundillo lace making; and Alice Chéverez teaching indigenous pottery making. Workshops took place at ICR and at locations in the Puerto Rican community. The trainings were free with some materials costs paid by participants; workshops were bilingual.

The weeklong workshops were intensive apprenticeship sessions designed for local artists who already had a level of skill in the tradition being taught or a closely related art form. The purpose is to develop further the skills of artists committed to a tradition so that they will be able to pass it on and perhaps market their work. The last day of each workshop was open to the public. The two music-oriented workshops (cuatro and pandero-making) celebrated with impromptu concerts by participants. Artworks by the teaching artists were displayed in the exhibit.

Two follow-up mentorships were conducted by local traditional artists – Ana Lozada in cake decorating, and Mel Gonzalez in clay art work. They met regularly with workshop participants, encouraging them to continue producing, offering further training in techniques of the art form if necessary, and advising on marketing procedures and outlets.

An unexpected benefit from the workshops was the degree of interaction between the participants, many of whom did not know each other before. CCHAP noticed that while they were engaged in the art forms, participants talked openly about their lives and issues important to them. Such workshops could be a useful setting for social or other research projects because people feel relaxed and informal (and in fact this outcome stimulated the development of CCHAP’s Sewing Circle Project in 2007). During the last session colleagues from Centro Civico, an arts and social service organization in Amsterdam, New York visited the project and became very interested in the potential for arts workshops to enhance communication and information gathering. Also, two of the workshops were held at La Casa Elderly Housing on Park Street, where the seniors showed a great interest in the art activities.

Proportionate to its size, Connecticut has one of the largest Puerto Rican populations on the mainland, especially in the major urban areas of Bridgeport, New Haven, Hartford, and Waterbury. People arrived from the island in great numbers after World War II to work in both factories and fields, especially eastern Connecticut's tobacco farms. Puerto Ricans in Connecticut are characterized by their migration patterns - they generally don't consider themselves "immigrants" or "settlers" in the state; they came here for work and continue to live here but frequently travel back to the island which they often view as a paradise, a homeland to which they belong and will return. Their nostalgia for the island is undoubtedly heightened by the difficult conditions many Puerto Ricans experience here, especially in cities: considerable prejudice, urban violence, poor schools, as well as high prices and taxes. An often-mentioned statistic compares Connecticut's per capita income, which is the highest in the nation, with its responsibility for four of the country's poorest cities - those listed above. Although large, the Puerto Rican community here is seriously underserved by local cultural, educational, and social organizations.

The community's love for the island and its culture has enhanced Connecticut's cities, especially Hartford, the location of this project's activities. Latinos, primarily Puerto Ricans, make up 35% of Hartford's population. The heart of the community is Park Street, the main thoroughfare in the Puerto Rican neighborhood known as Frog Hollow. Botanicas, bakeries, music clubs, bodegas, and restaurants named for Puerto Rican towns make this a vibrant center of constant activity. Artistic, social, and cultural practices within the community show a regular and active maintenance of beloved traditions which link urban Puerto Ricans to the island, and many return regularly for visits. The primary goal of this project was to reinforce the patterns of cultural practice and remembrance.

Additional materials exist in the CCHAP archive for these events and artists.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.

Status

Not on viewIlka Robles

July-September 2003

Ilka Robles

June-August 2003