Tibetan Artists

SubjectPortrait of

Tsultim Lama

(Tibetan)

SubjectPortrait of

Jampa Tsondue

(Tibetan, born 1959)

SubjectPortrait of

Tsering Yangzom

(Tibetan)

Date1996; 2002 February 17; 2006

MediumPhotography; color slide on plastic in cardboard mount

ClassificationsGraphics

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

CopyrightIn Copyright

Object number2015.196.237.1-.17

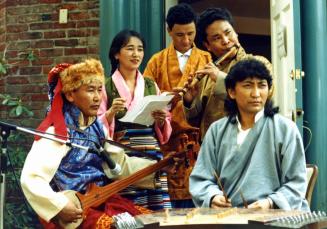

DescriptionSlides showing Tibetan artists at the Benton Museum at the University of Connecticut and at the "Auspicious Signs: Tibetan Arts in New England" exhibit, February 2002.

2015.196.237.1: Slide showing Tibetan weaver Tsultim Lama demonstrating loom weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.2: Slides showing Tibetan artist Jampa Tsondue painting a thangka at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.3: Slide showing the Auspicious Signs: Tibetan Arts in New England installation at the gallery at the Institute for Community Research

2015.196.237.4: Slide showing Tibetan thangkas on display at the Mystical Arts of Tibet exhibit at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.5: Slide showing woman Tibetan weaver Tsultim Lama demonstrating loom weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.6: Slide showing Tsering Yangzom turning the tablets to weave a belt on her loom, at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.7: Slide showing woman Tibetan weaver Tsultim Lama demonstrating loom weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.8: Slide showing Tsering Yangzom preparing her backstrap loom at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.9-.10: Slides showing Tsering Yangzom turning the tablets to weave a belt on her loom, at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.11: Slide showing textiles woven by Tsering Yangzom - belts, apron (top left) and blanket (top right)

2015.196.237.12: Slide showing Tsering Yangzom demonstrating her tablet weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.13: Slide showing Tsultim Lama beating down the warp threads on a carpet she is weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.14: Slide showing Tsultim Lama weaving, balls of yarn and finished rugs visible, at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.15: Slide showing woman Tibetan weaver Tsultim Lama demonstrating loom weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.16: Slide showing view of the belt Tsering Yangzom is weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.17: Slide showing view of Tsering Yangzom beating down the warp threads on a belt she is weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

NotesSubject Note: "The Mystical Arts of Tibet," a traveling exhibit displayed at the William Benton Museum of Art at the University of Connecticut in 2002, featured demonstrations by Connecticut Tibetan artists. Weavers Tsultim Lama and Tsering Yangzom set up their looms at the Museum to show their traditional weaving techniques to audiences. A brochure for The William Benton Museum of Art, University of Connecticut, Winter/Spring 2002, is also in the CHS collection (2015.196.92.13).2015.196.237.1: Slide showing Tibetan weaver Tsultim Lama demonstrating loom weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.2: Slides showing Tibetan artist Jampa Tsondue painting a thangka at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.3: Slide showing the Auspicious Signs: Tibetan Arts in New England installation at the gallery at the Institute for Community Research

2015.196.237.4: Slide showing Tibetan thangkas on display at the Mystical Arts of Tibet exhibit at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.5: Slide showing woman Tibetan weaver Tsultim Lama demonstrating loom weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.6: Slide showing Tsering Yangzom turning the tablets to weave a belt on her loom, at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.7: Slide showing woman Tibetan weaver Tsultim Lama demonstrating loom weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.8: Slide showing Tsering Yangzom preparing her backstrap loom at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.9-.10: Slides showing Tsering Yangzom turning the tablets to weave a belt on her loom, at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.11: Slide showing textiles woven by Tsering Yangzom - belts, apron (top left) and blanket (top right)

2015.196.237.12: Slide showing Tsering Yangzom demonstrating her tablet weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.13: Slide showing Tsultim Lama beating down the warp threads on a carpet she is weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.14: Slide showing Tsultim Lama weaving, balls of yarn and finished rugs visible, at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.15: Slide showing woman Tibetan weaver Tsultim Lama demonstrating loom weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.16: Slide showing view of the belt Tsering Yangzom is weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

2015.196.237.17: Slide showing view of Tsering Yangzom beating down the warp threads on a belt she is weaving at the Benton Museum, UConn

Subject Note: In 1998 weaver Linda Hendricksen visited Torrington to meet Tsering Yangzom and discuss her method of tablet weaving. Linda was a paid consultant providing accurate descriptions of Tsering Yangzom’s weaving that would be used in the video of three Connecticut Tibetan artists produced by CCHAP/Lynne Williamson in 1998 (videography by Winifred Lambrecht). This video is in the CCHAP archive, 2015.196.607.

Linda’s suggested general descriptions of Tsering Yangzom’s weaving are these:

“Tsering Yangzom brought some of her weaving tools with her to Connecticut

in 1992, and uses them to weave traditional patterned belts up to six

inches wide. The technique she is using here is called "tablet weaving",

and her tools consist of leather tablets, a wooden beater, and a wide

strap. The square leather tablets have a hole in each corner through which

Tsering threads the warp yarns. To weave, the yarns must be held under

tension. One end of the warp is attached to the strap which she wears low

around her waist, and the other end is attached to the wall. She can

tighten the tension on the warp yarns by leaning backward, or loosen it by

leaning forward. Notice that the tablets keep the tensioned yarns divided

so that half of them are up and half are down. Each time she turns the

pack of tablets, some of the warp yarns switch places (half that are up go

down and half that are down go up). Tsering can weave different patterns

and structures by changing the way she flips and rotates the tablets.

I'm not sure what her term “thak ti” refers to - the tablets, or perhaps the whole

set up? Tablet weaving is usually called an "off loom" technique. She is

using a backstrap method to tension the warp, but I think the term

"backstrap loom" is generally used to refer to something with heddle rods

and shed sticks rather than tablets.

She is doing warp twining in the video, but the slides show that she also

does the double faced technique, which is a different structure (three span

warp floats in alternate alignment, with twining occurring only at the

color interchange). Tablet weaving is the general term, while warp twining

is one of the many possible structures. Warp twining occurs when the

tablets are turned in one direction, and the four strands of yarn in each

tablet twist around each other. With horizontal stripes, (all colors arranged in the same position throughout the pack) all the colors change in the band after every two turns. With other common warp twined patterns, such as chevrons or

diamonds, some of the colors would change with every turn.”

Subject Note for 2015.196.237.2: Religious painting holds great importance in Tibetan Buddhism. Vast stores of Buddhist knowledge and doctrine are written in books housed in monasteries. Paintings both large and small illustrate these texts by depicting central figures and deities, stories of their lives, as well as charts of medical knowledge and elements of doctrine. Tibetan Tantric Buddhism practices visualization as a way to transform the self, to "identify with" Buddha and other deities, and to work toward enlightenment by bringing principles of wisdom and compassion into one's life. By viewing and meditating deeply upon a painting, one's own character can become imbued with the qualities of the figure represented. Both lay people and lamas commission paintings for devotional purposes as well as for aiding health or for teaching Buddhist doctrine.

The usual form of such painting in Tibet is the thangka, a painted scroll which can be rolled up for storage or transport. Thangka painting's origins and influences are complex, going back to 7th century India, with evolution over the centuries affected by Nepali and Chinese styles. Painting methods have also developed over hundreds of years, and are strictly followed by artists. Jampa Tsondue's training included techniques of canvas preparation, mixing pigments, measurement, outlining and drawing of the design, painting, shading, finishing, and mounting. The exquisite care and skill needed to create an authentic thangka make the costs of commissioning one very high. According to religious tradition, thangkas should not be made and sold in a market. Today, however, this does happen. In America, the difficulty of obtaining the right materials, as well as finding time to devote to such labor-intensive art, has been a challenge for Jampa and other artists.

The process of creating a thangka requires several steps. First a piece of pure cotton is hemmed on all sides then stitched to four bamboo sticks, making a flexible frame. These sticks are attached by strong thread to a larger wooden frame which holds the cloth taut and stretches it when the thread is pulled. An animal hide glue is applied to both sides of the cloth, scraping to make sure no particles remain on the surface. After the cloth is stretched and dried, one or two coats of chalk or clay gesso are applied. Jampa then rubs the smooth side of a conch shell over it to press the gesso into the "holes" in the cotton, making the surface like paper. Next, measurements and calculations determine the exact center to create an axis on the canvas for the drawing. An experienced artist like Jampa can draw the design freehand; sometimes for complicated figures a tracing is made from a book or master draftsman's work. Qualities and proportions of all the deities are set out in exquisitely detailed iconographies within Buddhist texts - the artist does not alter these.

After the sketch is outlined in ink, painting begins by applying base colors one at a time. Pigments are natural minerals crushed and mixed with water and herbs, sometimes with a little glue. A variety of shading and toning techniques are used very carefully and subtly throughout the painting. Outlining details are added as well as facial features. Twenty-four carat gold paint is usually applied for patterns on clothes or ornaments, then burnished. The completed thangka is often encased in a silk brocade frame backed by muslin, with bamboo and cedar dowels at top and bottom for hanging or rolling up. Thangkas used in religious ceremonies are consecrated by a lama.

Additional materials exist in the CCHAP archive for this community. Biography notes exist for all the artists.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.

Status

Not on viewPenpa Tsering

2015 July 6

Jampa Tsondue

2018 March 10

Penpa Tsering

2016 July 6

Haris Gusta Guya

2011 November 4