Cambodian Dancers Preparing for Performance

SubjectPortrait of

Somaly Hay

(Cambodian, 1959 - 2016)

SubjectPortrait of

Sophanna Keth

(Cambodian)

SubjectPortrait of

Sotha Keth

(Cambodian)

SubjectPortrait of

Sokphury Yos

PhotographerPhotographed by

Gale Zucker

Photographer(.14) Photographed by

Phillip Fortune

Date1994 September 17

MediumPhotography; color slides on plastic in cardboard mount

ClassificationsGraphics

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

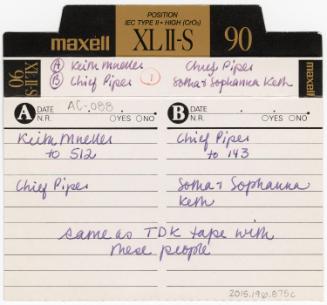

DescriptionSlides of Somaly Hay taken as part of the Living Legends exhibition project. Photos taken by Gale Zucker, except 2015.196.187.14, which was taken by Phillip Fortune and 2015.196.187.6, which was donated by the artist.

(.1) A crown being affixed to costumed dancer Sokphury Yos by her mother, costume maker Sophanna Keth Yos.

(.2) Several people helping dancer Somaly Hay into her costume. Curator Lynne Williamson on the left.

(.3) A woman attaching a flower to a young costumed dancer’s hair.

(.4) Dancer Somaly Hay being helped into her costume by multiple people, including Sokphury Yos (left) and Lynne Williamson (top).

(.5) Somaly Hay (left) and a young woman (right) onstage in a contemporary story.

(.6) Somaly Hay in queen’s costume that was displayed in the exhibition. The skirt is material from Cambodia; the other clothes and all embroidery done by Sophanna Keth. Crown and jewelry made by Sotha Keth.

(.7) Sophanna Keth Yos adjusting Sokphury Yos' crown.

(.8) Sokphury Yos preparing her costume.

(.9) A dancer’s arm being fitted for jewelry.

(.10) Sophanna Keth Yos helping her daughter Sokphury Yos to prepare backstage.

(.11) Somaly Hay being sewn into her costume.

(.12) Sokphury Yos backstage adjusting her crown with Sophanna Keth Yos assisting.

(.13) Somaly Hay onstage in one of the male roles.

(.14) Part of the dance costumes and jewelry made by Sophanna Keth Yos and Sotha Keth. Photo by Phillip Fortune.

(.15) Sophanna Keth Yos adjusting the crown worn by Sokphury Yos.

(.16) Somaly Hay onstage in one of the male roles.

(.17) A crown made by Sotha Keth displayed in the exhibit.

(.1) A crown being affixed to costumed dancer Sokphury Yos by her mother, costume maker Sophanna Keth Yos.

(.2) Several people helping dancer Somaly Hay into her costume. Curator Lynne Williamson on the left.

(.3) A woman attaching a flower to a young costumed dancer’s hair.

(.4) Dancer Somaly Hay being helped into her costume by multiple people, including Sokphury Yos (left) and Lynne Williamson (top).

(.5) Somaly Hay (left) and a young woman (right) onstage in a contemporary story.

(.6) Somaly Hay in queen’s costume that was displayed in the exhibition. The skirt is material from Cambodia; the other clothes and all embroidery done by Sophanna Keth. Crown and jewelry made by Sotha Keth.

(.7) Sophanna Keth Yos adjusting Sokphury Yos' crown.

(.8) Sokphury Yos preparing her costume.

(.9) A dancer’s arm being fitted for jewelry.

(.10) Sophanna Keth Yos helping her daughter Sokphury Yos to prepare backstage.

(.11) Somaly Hay being sewn into her costume.

(.12) Sokphury Yos backstage adjusting her crown with Sophanna Keth Yos assisting.

(.13) Somaly Hay onstage in one of the male roles.

(.14) Part of the dance costumes and jewelry made by Sophanna Keth Yos and Sotha Keth. Photo by Phillip Fortune.

(.15) Sophanna Keth Yos adjusting the crown worn by Sokphury Yos.

(.16) Somaly Hay onstage in one of the male roles.

(.17) A crown made by Sotha Keth displayed in the exhibit.

Object number2015.196.187.1-.17

CopyrightCopyright Held By Gale Zucker

NotesSubject Note: These images show Cambodian dancers getting ready for a performance on September 17, 1994. Preparing the dancers for a performance is a painstaking process. The costumes must be tightly fitted to the dancers, which means that Sophanna and other helpers sew the garment once the dancer puts it on, then afterwards they have to have the costume cut to take it off. Their hair has to be coiled under the crown, or decorated with flowers if they are not wearing a crown. The crown has to be carefully placed on the head, and affixed so that it does not fall off.

Biographical Note: Brother and sister, Sotha Keth and Sophanna Keth Yos, lived in the New London area near their sister Somaly Hay, a classical Cambodian dancer. The family members who survived the Khmer Rouge genocide, which destroyed so much of Cambodia and its culture from 1974-1979, fled to the United States in 1981, and Sophanna followed in 1987. In presenting and teaching Cambodian dance, Sotha, Somaly, Sophanna, and their extended family of friends, colleagues, and relatives were dedicated to helping young Cambodian people retain a sense of Cambodian cultural values through knowledge of their traditions.

One of the problems dancers like Somaly faced after moving here was finding traditional performance costumes. A highly specialized, elaborate art in itself, costume making depends on reproducing stylized clothing forms for the different roles of the classical dance repertoire. Contact with Cambodia was difficult at that time, making the proper materials, patterns, or examples of costume designs unavailable or prohibitively expensive. Sotha and Sophanna began the process of learning and then making the intricate costumes for Somaly, using materials that could be found in America. Sotha began to design the dance crowns relying on his memory, pictures of classical Cambodian art from library books, and an imaginative, experimental approach to using new materials. "I try to find materials, whatever we could find here in the U.S., to join together, glue, or make by hand, cut and chisel, to make the piece. Finally we did one, then turned to another one because there are so many different crowns needed." He constructed crowns in a variety of ways, refining his methods through trial and error over the years. Most were made of papier mache, painted and covered with copper or aluminum highlights. Sotha had to buy a lathe and learn woodworking, because wood is often the best material for a crown's tall embellishments. The paint must evoke the gold of original crowns, but finding the right shade was difficult. If he could afford it, Sotha would apply gold leaf. He traveled to as many of Somaly's performances as possible, to see how the crowns fit and wear. "I try to make the crowns as light as possible, because the performance takes a couple of hours plus the time it takes to put on the costumes...I want them to feel comfortable. If they feel nice the performance will be good also. If the crown is heavy...they will get sore and tired and the performance will not be good. Whatever the performer feels, that's what I feel too."

Like Sotha, Sophanna's memory of watching dancers at the palace helped her design traditional clothes. She also studied books, slides, and old films showing figures on temple carvings, because dance roles and costumes were often drawn from these beings. Sophanna sewed and embroidered the clothes, adding thousands of beads and sequins by hand to make the costume catch the light and look like gold and silver. Her work did not end there, as she needed to sew parts of the costume onto the dancer before the performance, and cut her out of it afterwards. Sophanna taught her daughter Sokphury how to sew the costumes, since Sokphury has learned to dance with Somaly. "Children came (to America) in the war, they come here very little and grow up here...they don't know their own culture! hey ask me, 'What is that worn for?' I say, 'That is your own culture - we wear this for classical dance.' They are interested! At least some youngsters get to know their culture...Some Cambodian ladies came (to a performance in Chicago) and they were so excited because they lost their culture for a long time and now they see it again."

Biographical Note: Somaly Hay was a Cambodian court dancer trained from a very young age at the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh by revered teachers Soth Sam On, Aum Prong, and Chhea Samy. Cambodian classical dance has been part of royal court life in Cambodia for over a thousand years. On the walls of the temples at Angkor Wat, apsara, celestial dancers carved in stone, have provided the inspirations for court dance characters. Court dance is essentially a female tradition, with women performing the main roles of prince, princess, and Giant. An unusually versatile artist, Somaly could dance each of these characters, and specialized in the difficult role of the Giant. For this role she was mentored by the master of all masked dances who also had extensive knowledge of all roles, dances, songs, history, and repertoire in Cambodian court dance. This teacher gave Somaly deep insights into the secret things that she had done when she was a dancer. Somaly dedicated her own teaching to the memory of this master, Soth Sam On.

During the Khmer Rouge reign of terror from 1975-1979, eleven members of Somaly’s family were killed. Surviving the upheaval in their country through strength, intelligence, and determination, Somaly along with her husband and brother escaped to the U.S. in 1981, and other family members followed later. She was one of the few court dancers remaining alive who had learned in the traditional way. In the U.S., Somaly’s husband Khandarith sometimes accompanied her performances as a vocalist, while her brother, Sotha, and sister, Sophanna, created elaborate costumes for her roles. From 1991 to 1995, she was a master dancer in the Cambodian Artists Project at Jacob’s Pillow, and contributed to an important film documentary project on Cambodian dance. As a performer Somaly danced with the Apsara Ensemble led by the renowned musician Sam Ang Sam. She performed either solo or as part of a troupe at organizations including Connecticut College, Angkor Dance Theatre, and Cambridge Multicultural Council, as well as in New York at the Asian Music Society and World Music Institute. Somaly was deeply involved in New England Cambodian community activities, especially New Year celebrations and performances at local temples.

The Connecticut Commission on the Arts recognized Somaly as a Master Teaching Artist, and she won a Commission Fellowship Award for choreography in 1999. In addition to residencies in schools from Connecticut to Alaska, Somaly taught folk, social, and classical dance to many young Cambodians in their communities. Somaly also trained her daughters and nieces to dance with her, and mentored three apprentices over four years in CCHAP’s Southern New England Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program. Somaly produced an instructional video of the roles and gestures of Cambodian dance for distance learning students. In 2015, Somaly received a special Governor’s Citation from the State of Connecticut. She passed away in 2016.

“As a classical Cambodian dancer trained at the Royal Palace from childhood, I continue to perform in America. I also teach Cambodian classical, folk, and social dance to Cambodian students in Connecticut and Rhode Island, because my whole family feels a commitment to preserving and passing on our culture. Many Cambodian children are born here now - we want them to understand themselves as Cambodian AND American. I serve as a Connecticut Commission on the Arts Master Teaching Artist, giving residencies in schools, performing with children, and working with teachers to incorporate my art into their curriculum.

One of my greatest loves is to create new dances based on Cambodian myths and folk tales performed in the classical court style, as I did for the Cambodian Artists Project at Jacob's Pillow and for the Merrimack Repertory Theater in Lowell, Massachusetts, where there is a very large Cambodian population. In 1994, I developed and choreographed a story called Strength of Spirit at Connecticut College. The story is, sadly, very appropriate to young Cambodians today in the U.S., as it deals with the problems of peer pressure and substance abuse. My dance presented culture and family as ways to strengthen a young girl's resistance to temptations and forge her own identity. It is hard to find the number of trained Cambodian dancers needed to perform the traditional dance stories or my new pieces. That is why I am eager to teach the next generation of dancers - including my two daughters - who can then become part of a New England Cambodian dance ensemble. I have worked with a videographer to record the essential elements of Cambodian dance: the kbach (postures) which are crucial to the correct portrayal of the central characters in the dance dramas. I can demonstrate these "building blocks" of choreography, then show how they are woven together through movement and expression to create the dance. This video provides young dancers with the best examples of form, so they can practice outside of class, and it documents the thousand-year-old memory of Cambodian dance.”

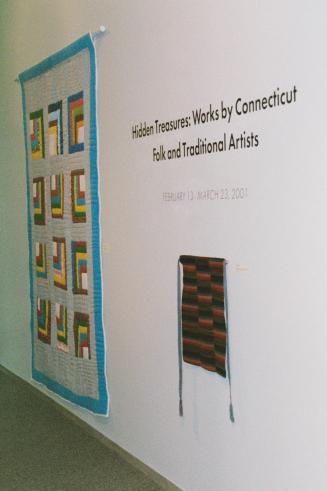

Subject Note: "Living Legends: Connecticut Master Traditional Artists" was a multi-year project to showcase the excellence and diversity of folk artists living and practicing traditional arts throughout the state. The first CCHAP Director, Rebecca Joseph, developed the first exhibition in 1991, displaying photographic portraits along with art works, and performances representing fifteen artists from different communities, at the Institute for Community Gallery at 999 Asylum Avenue in Hartford. In 1993, the next CCHAP Director, Lynne Williamson, organized two exhibitions of the photographic portraits from the original Living Legends exhibit, at the State Legislative Offices and at Capital Community-Technical College in Hartford. The photographs were also displayed in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, DC in October 1994, with the help of Connecticut Representative Nancy Johnson. Also in 1993, a grant from NEA Folk Arts was awarded to CCHAP to expand and tour the original exhibit and create a video to accompany it. The Connecticut Humanities Council and the Connecticut Commission on the Arts supported an exhibit catalogue and a performance series. CCHAP began fieldwork around the state in 1994 to document several of the artists involved in the first exhibit and add new artists. The expanded version of Living Legends opened at ICR's Gallery at its new office space at 2 Hartford Square West, then traveled to several sites in 1994 and 1995, including the Norwich Arts Council, the Torrington Historical Society, and the New England Folklife Center, Boott Mills Museum at Lowell National Historical Park in Lowell Massachusetts. CCHAP along with folklorist David Shuldiner produced a video based on images taken of the artists at work and audio interviews conducted with them. Portraits and images of the artists working were taken by photographer Gale Zucker. A catalogue of the images, art works, and texts based on the artist interviews was compiled by CCHAP and designed by Dan Mayer who also served as the exhibition designer.

Thirteen visual artists were included in the second Living Legends project: Eldrid Arntzen, Norwegian rosemaling; Qianshen Bai, Chinese seal carving; Katrina Benneck, German scherenschnitt; Alice Brend, Pequot ash basket making; Romulo Chanduvi, Peruvian wood carving; Laura Hudson, African-American quilt making; Ilias Kementzides, Pontian Greek lyra making and playing; Sotha Keth and Sophanna Keth Yos, Cambodian dance costume making; Keith Mueller, decoy carving; Bernabela Quinones, Puerto Rican mundillo lace; Walter Scadden, decorative ironwork; Nucu Stan, Romanian straw pictures. Five performing artists were presented during the first Living Legends project: Sonal Vora, Indian Odissi dance; Somaly Hay, Cambodian court dance; Ilias Kementzides, Pontian Greek lyra; Abraham Adzenyah, Ghanaian music and drumming; and La Primera Orquesta de Cuatros, Puerto Rican cuatro group.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.On View

Not on viewKeith Mueller

1991-1992