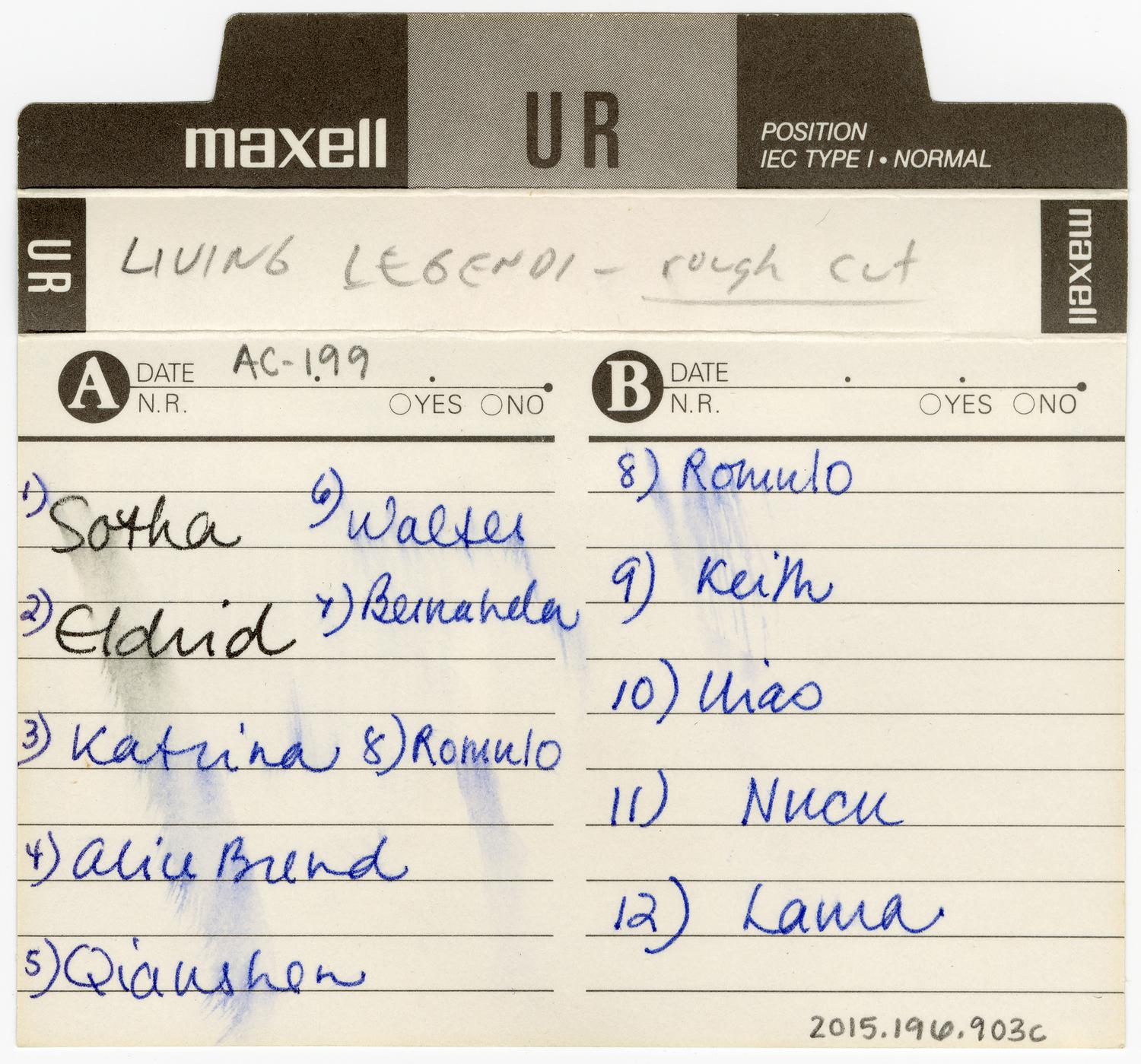

Living Legends Project: Qianshen Bai

SubjectPortrait of

Qianshen Bai

Chinese

PhotographerPhotographed by

Gale Zucker

Photographer(.20) Photographed by

Phillip Fortune

Date1994

MediumPhotography; color slides on plastic in cardboard mount

ClassificationsGraphics

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

DescriptionSlides of Qianshen Bai taken as part of the Living Legends exhibition project. Slides were photographed by Gale Zucker except (.20), which was taken by Phillip Fortune.

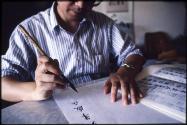

2015.196.145.1: Slide of Qianshen Bai holding calligraphy brush with ink

2015.196.145.2: Slide of Qianshen Bai, completed two characters

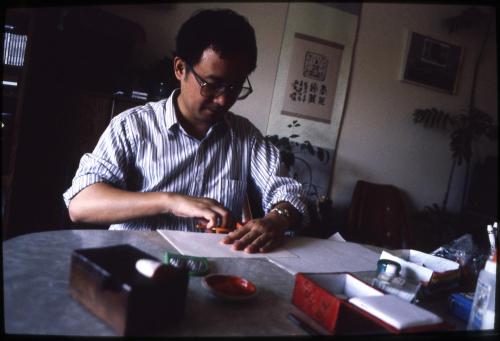

2015.196.145.3: Slide of Qianshen Bai carving seal

2015.196.145.4: Slide of Qianshen Bai applying oval seal

2015.196.145.5: Slide of stamped oval seal

2015.196.145.6: Slide of Qianshen Bai applying rectangular seal

2015.196.145.7: Slide of Qianshen Bai holding paper on table

2015.196.145.8: Slide showing vice-like wooden box used to hold seals while carving

2015.196.145.9: Slide showing Bai mixing pigment

2015.196.145.10: Slide of Qianshen Bai holding jar of pigment

2015.196.145.11: Slide of Qianshen Bai examining oval seal

2015.196.145.12: Slide of Qianshen Bai writing calligraphy in his workspace, distant view

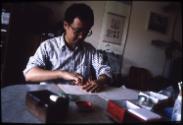

2015.196.145.13: Slide of Qianshen Bai, seated at workspace, distant view

2015.196.145.14: Slide of photograph related to Bai, five people standing

2015.196.145.15: Slide of photograph showing Bai demonstrating calligraphy at a meeting of the student calligraphy association at Peking University, 1981 or 1982.

2015.196.145.16: Slide showing Bai trimming paper

2015.196.145.17: Slide showing Bai discussing a calligraphy artwork at the Yale University Art Gallery.

2015.196.145.18: Slide showing Bai giving a talk with ornamental box in hand, at the Yale University Art Gallery.

2015.196.145.19: Slide showing Bai's calligraphy displayed during the Living Legends exhibit; Couplet, a poem in two parts, written in calligraphy. Reading from right to left, it translates as "The flowing water can be heard as music played by the earth. The beautiful mountain must be seen as a painting." In many Chinese homes calligraphic couplets hang in the center of the living room, with a painting in between. This reflects the tradition dating back to the T'ang Dynasty of hanging carved peach wood boards on either side of a gate to ward off sinister forces.

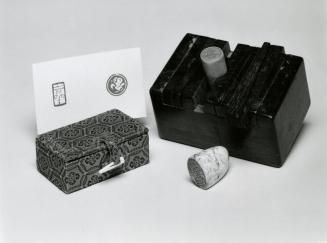

2015.196.145.20: Slide showing seals and box displayed during the Living Legends exhibit: left seal is "good luck" and right seal is "auspicious bird"

2015.196.145.21: Slide showing Bai applying stamp to paper

2015.196.145.22: Slide showing Bai holding newly carved seal

2015.196.145.23: Slide showing vice-like wooden box used to hold seals while carving; seal with character for "self-amusement" on top

2015.196.145.1: Slide of Qianshen Bai holding calligraphy brush with ink

2015.196.145.2: Slide of Qianshen Bai, completed two characters

2015.196.145.3: Slide of Qianshen Bai carving seal

2015.196.145.4: Slide of Qianshen Bai applying oval seal

2015.196.145.5: Slide of stamped oval seal

2015.196.145.6: Slide of Qianshen Bai applying rectangular seal

2015.196.145.7: Slide of Qianshen Bai holding paper on table

2015.196.145.8: Slide showing vice-like wooden box used to hold seals while carving

2015.196.145.9: Slide showing Bai mixing pigment

2015.196.145.10: Slide of Qianshen Bai holding jar of pigment

2015.196.145.11: Slide of Qianshen Bai examining oval seal

2015.196.145.12: Slide of Qianshen Bai writing calligraphy in his workspace, distant view

2015.196.145.13: Slide of Qianshen Bai, seated at workspace, distant view

2015.196.145.14: Slide of photograph related to Bai, five people standing

2015.196.145.15: Slide of photograph showing Bai demonstrating calligraphy at a meeting of the student calligraphy association at Peking University, 1981 or 1982.

2015.196.145.16: Slide showing Bai trimming paper

2015.196.145.17: Slide showing Bai discussing a calligraphy artwork at the Yale University Art Gallery.

2015.196.145.18: Slide showing Bai giving a talk with ornamental box in hand, at the Yale University Art Gallery.

2015.196.145.19: Slide showing Bai's calligraphy displayed during the Living Legends exhibit; Couplet, a poem in two parts, written in calligraphy. Reading from right to left, it translates as "The flowing water can be heard as music played by the earth. The beautiful mountain must be seen as a painting." In many Chinese homes calligraphic couplets hang in the center of the living room, with a painting in between. This reflects the tradition dating back to the T'ang Dynasty of hanging carved peach wood boards on either side of a gate to ward off sinister forces.

2015.196.145.20: Slide showing seals and box displayed during the Living Legends exhibit: left seal is "good luck" and right seal is "auspicious bird"

2015.196.145.21: Slide showing Bai applying stamp to paper

2015.196.145.22: Slide showing Bai holding newly carved seal

2015.196.145.23: Slide showing vice-like wooden box used to hold seals while carving; seal with character for "self-amusement" on top

Object number2015.196.145.1-.23

CopyrightIn Copyright

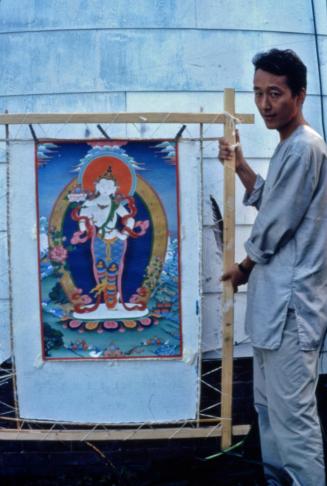

NotesBiographical Note: Qianshen Bai began his art as a calligrapher in China 20 years ago, winning the National Calligraphy Competition for University Students in 1982. He first studied with a master teacher while pursuing a career in banking in Shanghai and continues his research and practice of calligraphy now as a PhD. student in art history at Yale. Qianshen is also an accomplished seal carver, which he describes as "writing in stone." Small stone seals are inscribed with calligraphic characters or ancient symbols. Their imprints have traditionally been used to authenticate documents, signify ownership, or sign a work of art. Seal carving has become an art form in itself, one characterized by both long historical heritage and new contemporary expressions. Qianshen began to learn calligraphy under the guidance of a master artist in 1972 during China's Cultural Revolution. A revered and popular writing and art form in China for thousands of years, calligraphy also served a valuable function for Qianshen in his work in a Shanghai bank. There, the tradition of calligraphy is taken seriously, because “if you have a check or certificate of deposit, we don't type it - we write it. You have to write beautifully otherwise people will think the certificate is not so serious - it doesn't look like money!" While attending Peking University he organized a student calligraphic society with friends, winning the National Calligraphy Competition for University Students in 1982. His interest in seal carving developed when one of the calligraphy group members, himself a skilled carver, taught Qianshen the art of etching tiny calligraphic characters on stone seals.

Seal carving is a miniaturist's art with a practical purpose. Historically, seals have been used to authenticate documents, signify ownership, or sign works of art and literature among the educated, commercial, and bureaucratic classes. Many Chinese, especially those occupied in business or the arts, still use one or more seals to establish ownership or creativity. New schools and genres of carving have arisen, reflecting the opening up of traditionally elite arts to a wider public in modern China. Qianshen uses an "iron brush" to etch ancient characters into stones selected for their subtle colors, textures, and markings. These small stone seals are inscribed with calligraphic characters or ancient symbols, a process he describes as "writing in stone." Often a person will use more than his or her given name, depending on the situation. For variety a name with a related meaning could be used, or a poetic name of one's home. Some people will also take a literary name, an epithet; and perhaps a studio name if they are artists. Qianshen has made a seal for his given name, one for his special name, and one with a studio name, which is "Cloud Studio - I wish I could be a white cloud floating in the sky so freely."

The production of seals requires a delicate calligraphic skill, as the stones are carved with script characters or similar pictorial figures like Qianshen's "auspicious bird." Another seal carries the common greeting "good luck". "In ancient China the character for sheep means good luck, because the sheep was the animal for sacrifice in worship of ancestors...this sacrifice will bring them good luck." The design is etched into the end of the seal stone with a small chisel, an "iron brush," in mirror image because when impressed it will be normal. Sometimes the character is positive, raised, and sometimes sunken for a white impression. To print, the seal is pressed into a cinnabar (sulphide of mercury) and oil paste.

When he was a doctoral candidate in Chinese art history at Yale University in the mid-1990s, Qianshen practiced both calligraphy and seal carving. In 1992, he co-organized an exhibit at the Yale Art Gallery entitled "The World Within a Square Inch: The Art of Chinese Seal Carving." He also developed an exhibit of Chinese calligraphers working in the last decade of the 20th century. Qianshen became Associate Professor of Art History at Boston University where in 2007 and 2013 he received grants to teach apprentice the elements of calligraphy under the Massachusetts Cultural Council’s Folk Arts Program.

Subject Note: Living Legends: Connecticut Master Traditional Artists was a multi-year project to showcase the excellence and diversity of folk artists living and practicing traditional arts throughout the state. The first CCHAP Director, Rebecca Joseph, developed the first exhibition in 1991, displaying photographic portraits along with art works and performances representing 15 artists from different communities, at the Institute for Community Gallery at 999 Asylum Avenue in Hartford. In 1993, the next CCHAP Director, Lynne Williamson, organized two exhibitions of the photographic portraits from the original Living Legends exhibit, at the State Legislative Offices and at Capital Community-Technical College in Hartford. The photographs were also displayed in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, DC in October 1994, with the help of Rep. Nancy Johnson. Also in 1993, a grant from NEA Folk Arts was awarded to CCHAP to expand and tour the original exhibit and create a video to accompany it. The Connecticut Humanities Council and the Connecticut Commission on the Arts supported an exhibit catalogue and a performance series. CCHAP began fieldwork around the state in 1994 to document several of the artists involved in the first exhibit, adding new artists. The expanded version of Living Legends opened at ICR's Gallery at its new office space at 2 Hartford Square West, then traveled to several sites in 1994 and 1995, including the Norwich Arts Council, the Torrington Historical Society, and the New England Folklife Center, Boott Mills Museum at Lowell National Historical Park in Lowell Massachusetts. CCHAP along with folklorist David Shuldiner created a video based on images taken of the artists at work and interviews conducted with them. Portraits and images of the artists working were taken by photographer Gale Zucker. A catalogue of the images, art works, and texts based on the artist interviews was compiled by CCHAP and designed by Dan Mayer who also served as the exhibition designer.

Thirteen visual artists were included in the new Living Legends project: Eldrid Arntzen, Norwegian rosemaling; Qianshen Bai, Chinese seal carving; Katrina Benneck, German scherenschnitt; Alice Brend, Pequot ash basket making; Romulo Chanduvi, Peruvian wood carving; Laura Hudson, African-American quilt making; Ilias Kementzides, Pontian Greek lyra making and playing; Sotha Keth and Sophanna Keth Yos, Cambodian dance costume making; Keith Mueller, decoy carving; Bernabela Quinones, Puerto Rican mundillo lace; Walter Scadden, decorative ironwork; Nucu Stan, Romanian straw pictures. Five performing artists were presented: Sonal Vora, Indian Odissi dance; Somaly Hay, Cambodian court dance; Ilias Kementzides, Pontian Greek lyra; Abraham Adzenyah, Ghanaian music and drumming; and La Primera Orquesta de Cuatros, Puerto Rican cuatro group.

The profound way these artists describe their inspirations, their intricate technical processes, and the dynamic tension they feel between traditional form and personal innovation within that form mark them as true creative masters. The artists featured in Living Legends had very different characters, stories, homelands, communities, art forms and techniques, but they were linked by their high level of artistic skill and a devotion to the traditions of their culture. The Living Legends project highlighted the way that cultural histories, technical information, aesthetic tastes, social values and other deep aspects of heritage can be communicated through the process and creation of traditional arts. Also, these artists express a strong desire to teach what they know to others, to "pass on the tradition." Community survival, memories of the past, and hopes for the next generation depend on exemplary culture bearers such as these.

Biographical Note: Gale Zucker is an experienced professional photographer and artist with a special interest in fiber arts. Her photojournalism has appeared in Forbes, Modern Maturity, Newsweek, the New York Times, and Yankee. She exhibits in Connecticut, New York, and New Hampshire and received a grant from the Minnesota Folklife Center to produce an audio-visual program. Her many commercial and arts-world clients include the National Endowment for the Arts, Modern Knitting, the Connecticut Health Foundation, Smithsonian Magazines, Penguin Random House, and Raytheon Technologies, among others. She collaborated with CCHAP on photography portraits and artists’ techniques/processes documentation for the Living Legends exhibit project from 1991-1994.

Additional audio, video, and/or photographic materials exist in the archive relating to this artist and this project.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.

On View

Not on view