Programs: Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival

Date2012-2018

MediumPaper

ClassificationsInformation Artifacts

Credit LineConnecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program collections

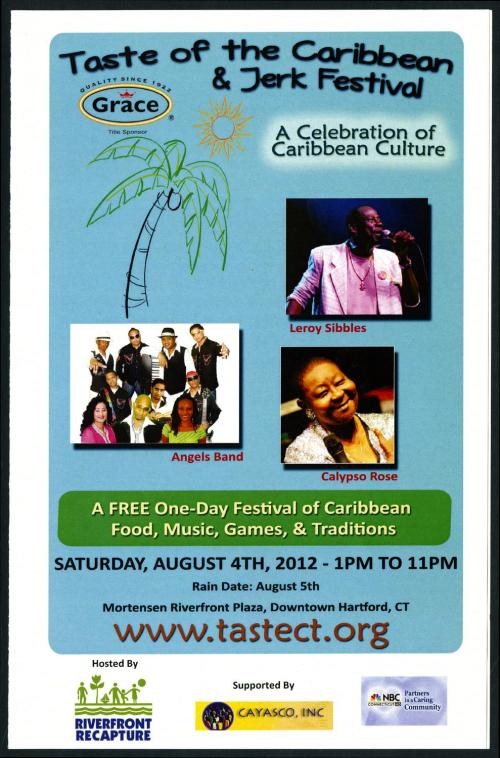

Description2015.196.71.1: brochure, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2012

2015.196.71.2: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2012

2015.196.71.3: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2013

2015.196.71.4: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2014

2015.196.71.5: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2015

2015.196.71.6: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2016

2015.196.71.7: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2017

2015.196.71.8: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2018

2015.196.71.2: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2012

2015.196.71.3: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2013

2015.196.71.4: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2014

2015.196.71.5: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2015

2015.196.71.6: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2016

2015.196.71.7: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2017

2015.196.71.8: program booklet, Taste of the Caribbean & Jerk Festival, 2018

Object number2015.196.71.1-.8

CopyrightIn Copyright

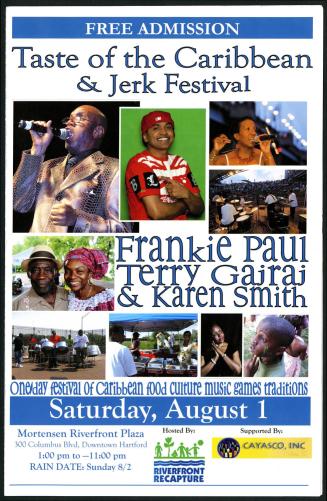

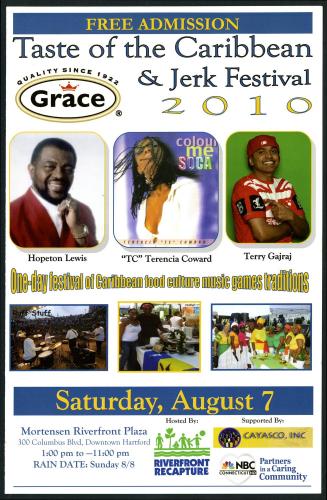

NotesSubject Note: The Taste of the Caribbean and Jerk Festival began as a single evening event and expanded into a day-long festival held since 2006 at the Riverfront Plaza at the beginning of Celebration Week. Billed as a “One day festival of Caribbean food, culture, music, games, traditions” the festival includes local and visiting performers, food vendors from a variety of Caribbean cultures, information booths, arts and crafts vendors, local and visiting dance groups, and since 2011, a procession of Mas dancers from CCHAP’s Mas Camp program in collaboration with CICCA, the Caribbean International Carnival Cultural Association.

Subject Note: A significant wave of West Indian immigration to the United States began in the 1940s. Many settled in the Hartford area because the labor shortage of World War II meant there were available jobs in the tobacco fields along the Connecticut River Valley. Men worked in the fields while women often found work as housekeepers, teachers, nurses, and aides. Local organizations helped transition new immigrants to Connecticut culture and offered friendship, housing, economic opportunities, and community connections. Today, Connecticut’s West Indian community includes immigrants from all the islands in the Caribbean. They have established significant sports, cultural, and social clubs, dance and music groups, and produce an annual week-long festival that attracts audiences from all over the Northeast. With Greater Hartford now being home to the third largest West Indian community in the nation, beloved traditions like Carnival have been transplanted and sustained here.

In 1962, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago claimed their Independence from Great Britain. Since that year, the West Indian Parade and Independence Celebration has been a highlight of Hartford’s summer activities. The week of activities includes many events taking place at the different island clubs around Hartford and features headlining musicians who perform at the West Indian Social Club. The celebration concludes with a parade and festival in Hartford featuring floats, steel band performances, and masqueraders displaying brilliant costumes.

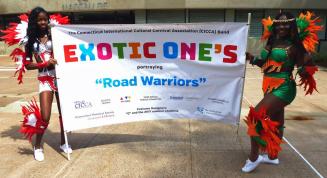

The Hartford celebration is based on Carnival, a pre-Lenten celebration of spring and renewal in the islands, especially Trinidad. Masquerading, or playing Mas is an essential part of Carnival. Mas represents a theatrical adoption and presentation of roles and characters that originally expressed mockery of upper classes. Colorful, often spectacular costumes designed by traditional Mas artists depict fanciful themes or current issues. Gossamer fabrics, plumes and feathers, sequins and gems used in previous years are recycled to express the new year’s themes. During Carnival parades, groups of masqueraders form bands and dance to calypso or soca music. As West Indians have spread out from the islands, Carnival has been transplanted to cities around the world during different times of the year. Mas and Carnival serve as central expressions of Caribbean cultural identity and heritage.

From 2011-2020, the Connecticut Cultural Heritage Arts Program at the Connecticut Historical Society partnered with the Connecticut Caribbean International Carnival Association to offer an annual summer youth employment program that trains Hartford youth in Carnival traditions central to their ethnic background. At the six-week “Mas Camp,” participants learned about the history and role of Carnival and masquerade. They designed and created their own Carnival costumes under the guidance of experienced Mas artists. The teens along with over two dozen volunteers, formed a Carnival Band that participated in several summer events showcasing Mas costumes totally made in Hartford. The beauty of the costumes displayed by Hartford’s own masqueraders in the parade and festival, along with the excitement of their dance routines, bring a tremendous energy and pride to the city’s West Indian communities. Mas Camp has helped to ensure that the Carnival tradition continues by training a new generation in the art of Mas making. In 2017, Mas Camp was selected as one of 50 exemplary youth programs nationwide by the National Arts and Heritage Youth Program.

Additional audio, video, and/or photographic materials exist in the archive relating to this community and these events.

Cataloging Note: This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services MA-245929-OMS-20.On View

Not on view